Solitaire abstract games

Steven Meyers' BoxOff has the feel of a classic solitaire abstract game. Brightly coloured pieces are distributed on a rectangular grid of squares and removed in pairs of like colour until the board is empty. It reminds me most of the old peg Solitaire, which dates back at least to the Seventeenth Century, which also handles pieces a pair at a time, albeit by jumping, unlike BoxOff. Peg Solitaire has the same objective as BoxOff, to empty the board—except of course for the very last piece in the former game. In my opinion, Steve's game is much better. The randomization of the board position supplies endless variety, like card solitaire. Moreover, the size of the board and number of colours used can be scaled up or down to suit the player, thereby altering the game's length and difficulty. Interesting strategies are emerging as I continue to play the game. Importantly, it is very easy to make a beautiful-looking BoxOff set inexpensively.

BoxOff was first presented in Games magazine in August 2013, and BoxOff puzzles ran in its successor, Games World of Puzzles, in May 2017, February 2018, and October 2018. However, I think we can add a little to the original Games article here, and BoxOff is so good that it deserves at least a second look. I do not think we need to present puzzles on this game, because it is so easy to construct your own set and produce puzzle after puzzle for yourself. There is a BoxOff app available for iOS, as well as a separate app available for Android. In both apps 100% of boards are solvable, and there is the option to take back your moves. Cameron Browne and Frederic Maire wrote a scholarly article about BoxOff called "Monte Carlo Analysis of a Puzzle Game." It appeared in Advances in Artificial Intelligence and describes some interesting mathematical results, including the fact that 8x6 BoxOff with three colours—the format given in the original Games article—is unsolvable in only about one in five thousand random initial setups.

BoxOff was first presented in Games magazine in August 2013, and BoxOff puzzles ran in its successor, Games World of Puzzles, in May 2017, February 2018, and October 2018. However, I think we can add a little to the original Games article here, and BoxOff is so good that it deserves at least a second look. I do not think we need to present puzzles on this game, because it is so easy to construct your own set and produce puzzle after puzzle for yourself. There is a BoxOff app available for iOS, as well as a separate app available for Android. In both apps 100% of boards are solvable, and there is the option to take back your moves. Cameron Browne and Frederic Maire wrote a scholarly article about BoxOff called "Monte Carlo Analysis of a Puzzle Game." It appeared in Advances in Artificial Intelligence and describes some interesting mathematical results, including the fact that 8x6 BoxOff with three colours—the format given in the original Games article—is unsolvable in only about one in five thousand random initial setups.

Rules

BoxOff can be played with sets of pieces consisting of three colours, four colours, or five colours. The fewer the colours, the easier the game. The number of pieces of each colour must be the same and must be an even number, because the pieces are removed from the board in pairs of the same colour. For example, four colours with 14 pieces each makes a good game on a 7x8 board, or five colours with 12 pieces each makes a more challenging game on a 6x10 board. Steve recommends five colours with 36 pieces each on a 12x15 board. I use a Renju board (15x15 points, so 14x14 squares) on which different board sizes can be marked off with painter's tape for experimentation—see the header image. The largest size I have tried, using the Renju board, is 10x12, with 24 pieces each of five different colours. Beautiful glass "gem" pieces can be sourced from craft stores, or even from dollar stores, quite inexpensively.

The pieces are shuffled and distributed randomly on the squares of the board. Pairs of pieces of the same colour are removed, pair by pair, until (hopefully) the board is empty. If you get stuck with pieces still on the board, which cannot be removed, the game is lost. Shuffle up the pieces and start again!

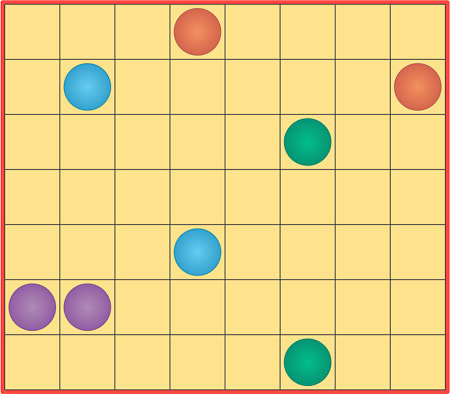

To remove a pair of pieces, they must lie at opposite corners of a rectangle that is otherwise empty of any other pieces. See the diagrams below with examples. Rectangles of length or width 1 also count. The smallest rectangle is 1x2 (or 2x1), in which a pair of like-coloured pieces are orthogonally adjacent. Your only choice at the beginning of a game is to remove such a pair. And those are all the rules. BoxOff is important as a solitaire game, in my opinion, because it is so natural and minimal.

BoxOff can be played with sets of pieces consisting of three colours, four colours, or five colours. The fewer the colours, the easier the game. The number of pieces of each colour must be the same and must be an even number, because the pieces are removed from the board in pairs of the same colour. For example, four colours with 14 pieces each makes a good game on a 7x8 board, or five colours with 12 pieces each makes a more challenging game on a 6x10 board. Steve recommends five colours with 36 pieces each on a 12x15 board. I use a Renju board (15x15 points, so 14x14 squares) on which different board sizes can be marked off with painter's tape for experimentation—see the header image. The largest size I have tried, using the Renju board, is 10x12, with 24 pieces each of five different colours. Beautiful glass "gem" pieces can be sourced from craft stores, or even from dollar stores, quite inexpensively.

The pieces are shuffled and distributed randomly on the squares of the board. Pairs of pieces of the same colour are removed, pair by pair, until (hopefully) the board is empty. If you get stuck with pieces still on the board, which cannot be removed, the game is lost. Shuffle up the pieces and start again!

To remove a pair of pieces, they must lie at opposite corners of a rectangle that is otherwise empty of any other pieces. See the diagrams below with examples. Rectangles of length or width 1 also count. The smallest rectangle is 1x2 (or 2x1), in which a pair of like-coloured pieces are orthogonally adjacent. Your only choice at the beginning of a game is to remove such a pair. And those are all the rules. BoxOff is important as a solitaire game, in my opinion, because it is so natural and minimal.

Entanglements

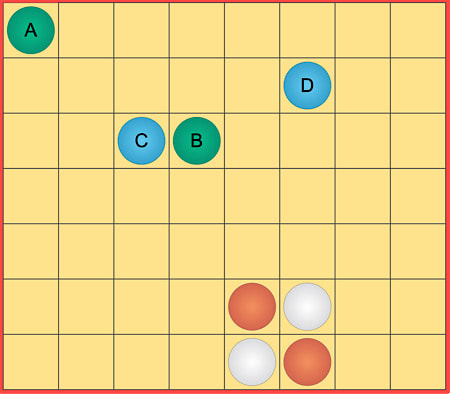

Now, if you set up your board and start removing pairs of pieces randomly, you are likely to run into positions that I refer to as entanglements, that will ruin your chances of winning. The diagram below on the left shows some examples of simple entanglements. As it stands, this position at the end of the game would illustrate a lost game. However, consider the entanglement of green and blue pieces in the top left: there may be green or blue pieces elsewhere on the board that can relieve the situation. If, for example, there is another blue piece in the bottom left of the board, then the pair including C could be removed. Subsequently, the green pair A and B can be removed, and there will be another blue piece somewhere, hopefully not too entangled itself, by which the blue D can be removed. A similar scenario can be envisioned with the green B first removed, using another green piece on the right. However, if green A or blue D are first removed, with a green or blue piece outside this arrangement, respectively, the remaining pieces are still entangled.

The pattern of red and white pieces is given to show the very simplest and smallest kind of entanglement.

Now, if you set up your board and start removing pairs of pieces randomly, you are likely to run into positions that I refer to as entanglements, that will ruin your chances of winning. The diagram below on the left shows some examples of simple entanglements. As it stands, this position at the end of the game would illustrate a lost game. However, consider the entanglement of green and blue pieces in the top left: there may be green or blue pieces elsewhere on the board that can relieve the situation. If, for example, there is another blue piece in the bottom left of the board, then the pair including C could be removed. Subsequently, the green pair A and B can be removed, and there will be another blue piece somewhere, hopefully not too entangled itself, by which the blue D can be removed. A similar scenario can be envisioned with the green B first removed, using another green piece on the right. However, if green A or blue D are first removed, with a green or blue piece outside this arrangement, respectively, the remaining pieces are still entangled.

The pattern of red and white pieces is given to show the very simplest and smallest kind of entanglement.

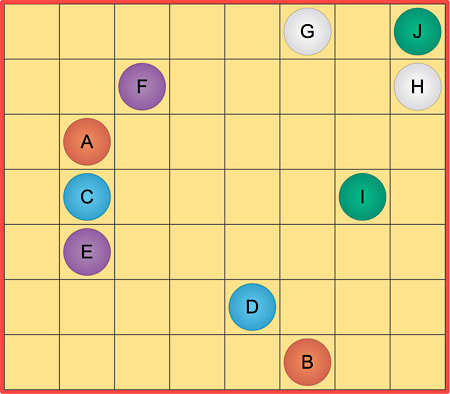

Of course, entanglements can be more complex than these, and the diagram above right gives some examples. To the left of the board, the red, purple, and blue pieces are entangled. If purple E can be eliminated, with another purple piece outside the position, then blue C and D fall, followed by red A and B, and lastly a fourth purple piece, hopefully, takes care of purple F. If any other piece is removed first, by another piece beyond this position, it remains entangled.

The green and white pieces in the top right are a simple entanglement, but, importantly, an entanglement in the corner. Entanglements rely on external pieces to be resolved. However, in the corner of the board like this, there can be no other pieces above or to the right that can unravel this entanglement—it must rely on external pieces below or to the left. There are fewer options to resolve corner entanglements, and corner entanglements are therefore often more tricky.

Of course, the board at the outset is one massive entanglement, aside from any pairs of orthogonally adjacent like-coloured pieces. Starting with one or more of these pairs, the goal is gradually to unravel the whole arrangement step by step.

Board size and number of colours

With the discussion of entanglements out of the way, I can explain the influence of the number of colours and the size of the board on how the game plays. With more colours, there are simply more and more difficult entanglements to unravel. Or look at it this way, with a greater number of colours, proportionately, there will be fewer pieces of the colour you need to unravel each entanglement.

Three colours makes for an easy game, generally, whereas five colours leads to much harder games. Four colours is a good medium choice, although keen players will prefer five colours for the challenge.

Regarding board size, larger boards have more pieces. Therefore, when trying to resolve a particular entanglement, there will simply be more pieces beyond this entanglement that can help unravel it. For a given number of colours, larger boards make for easier games, whereas smaller boards make for harder games. On a 2x2 board, for example, with two colours, the game is unsolvable if the red and white position occurs from Diagram 2—not all opening positions have a solution! A 7x8 board with four colours, as in the diagrams, works well for an easier game. If you want a tougher game, you can try five colours on a 6x10 board, or larger. As I mentioned above, sometimes I play on a 10x12 board with five colours for a long and challenging game!

Strategy

The designer of BoxOff made the following points about BoxOff strategy:

The green and white pieces in the top right are a simple entanglement, but, importantly, an entanglement in the corner. Entanglements rely on external pieces to be resolved. However, in the corner of the board like this, there can be no other pieces above or to the right that can unravel this entanglement—it must rely on external pieces below or to the left. There are fewer options to resolve corner entanglements, and corner entanglements are therefore often more tricky.

Of course, the board at the outset is one massive entanglement, aside from any pairs of orthogonally adjacent like-coloured pieces. Starting with one or more of these pairs, the goal is gradually to unravel the whole arrangement step by step.

Board size and number of colours

With the discussion of entanglements out of the way, I can explain the influence of the number of colours and the size of the board on how the game plays. With more colours, there are simply more and more difficult entanglements to unravel. Or look at it this way, with a greater number of colours, proportionately, there will be fewer pieces of the colour you need to unravel each entanglement.

Three colours makes for an easy game, generally, whereas five colours leads to much harder games. Four colours is a good medium choice, although keen players will prefer five colours for the challenge.

Regarding board size, larger boards have more pieces. Therefore, when trying to resolve a particular entanglement, there will simply be more pieces beyond this entanglement that can help unravel it. For a given number of colours, larger boards make for easier games, whereas smaller boards make for harder games. On a 2x2 board, for example, with two colours, the game is unsolvable if the red and white position occurs from Diagram 2—not all opening positions have a solution! A 7x8 board with four colours, as in the diagrams, works well for an easier game. If you want a tougher game, you can try five colours on a 6x10 board, or larger. As I mentioned above, sometimes I play on a 10x12 board with five colours for a long and challenging game!

Strategy

The designer of BoxOff made the following points about BoxOff strategy:

— The beginning of the game can be compared to acupuncture—the goal is to relieve the pressure points, which in BoxOff can be considered localities where several colours are tightly interlocked. If you wait to attend to these pressure points, you will likely run out of matching options later and therefore be stuck in an impossible position. Pressure points in the corner are the most urgent, then along the short sides, and then along the long sides. It is rare for there to be a pressure point in the centre that requires immediate attention, because of the plethora of matching options afforded by the favourable geography.

— Be aware when a single piece of a certain colour is a considerable distance from its fellows. Don't wait too long to think about what you’re going to match it with, or you might very well run out of options.

— Be aware when one colour is getting low. For instance, suppose there are 12 black stones left, 14 white stones left, and just 4 red stones left. You could be in big trouble with regard to eliminating red because of the very limited number of matching options. Don’t get low on a colour when there are still numerous stones of other colours on the board, unless you can see ahead exactly how the colour is going to be eliminated.

— When resolving a local pressure point early in the game, resist the temptation to play out the entire sequence. Leave a move or two undone. You can always come back to them later, but you will sometimes find—to your surprise—that these pieces end up being key to resolving a situation elsewhere.

I can add for clarification that if you can see a way to eliminate a colour completely, then do it! In fact my strategy at the outset is to examine the initial setup to see if I can find a way to remove one colour completely. If I can, then many potential entanglements are automatically resolved, and it is far easier to deal with the remaining colours. I think you can see this in the slideshow below, which shows the solution of a 7x8 four-colour game.

Steve Meyers was a valued contributor to the old series of Abstract Games. We covered his game Anchor in AG5 and then Orbit in AG12. His game BoxOff has a level of minimalism close to that of Hex, as well as the flexibility to make a solitaire abstract gaming experience as easy or as difficult as you like. BoxOff should become a classic. If you would like to discuss BoxOff with Steve, he is happy to receive email enquiries.