Vintage games

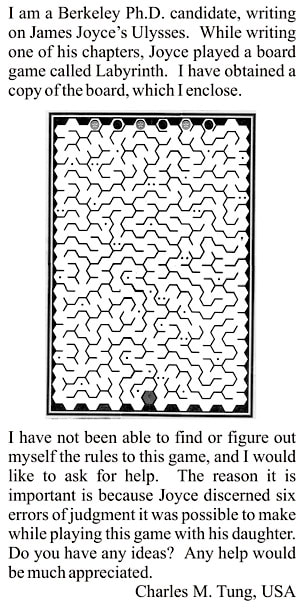

In 2005 I heard about a famous games magazine called Abstract Games. Because of my fascination with and interest in abstract strategic games it struck me hard that I had missed this one completely! After some asking around I obtained the name and address of the publisher and ordered the complete set. Sixteen issues were shipped. Subsequently, in AG15, from Autumn 2003, I discovered a letter from Mr. Charles M. Tung asking for information about a game:

In this letter, he refers to his research on James Joyce and the latter's book Ulysses in which he found the game mentioned. He gave a copy of the board and the name of the game “Labyrinth.” But he wanted to know more and especially how the game should be played. The main reason he asked for help was that he found it important to know how, as Joyce stated, it is possible to make six errors of judgement while playing the game.

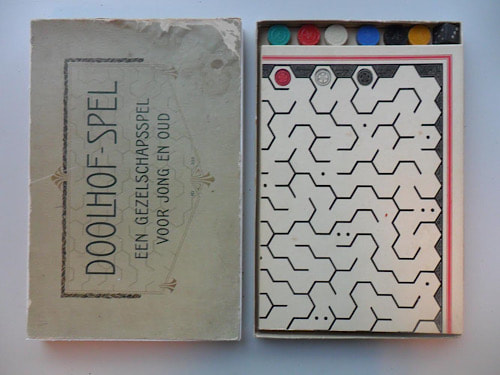

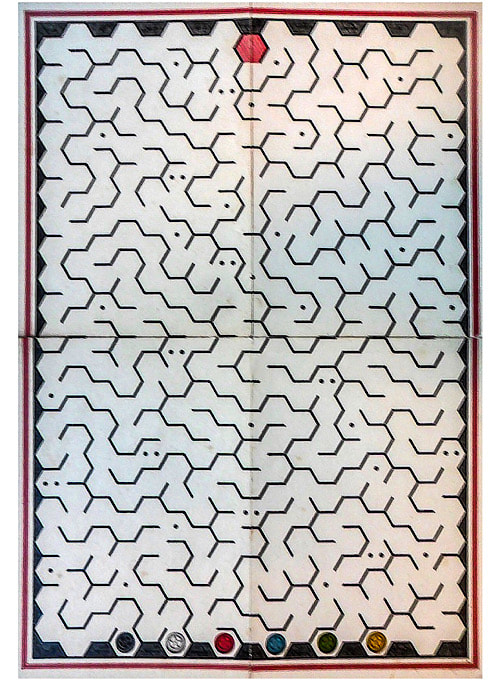

When I saw the board, I quickly recognized the game Mr. Tung was asking about as Het DOOLHOF-SPEL, a game that has been in my collection for decades. I had always thought it was a Dutch game from the late nineteenth century, although the set I have is not dated and neither does it include any information about the publisher. After reading Mr. Tung's letter, I began to see Labyrinth in a completely different light.

When I saw the board, I quickly recognized the game Mr. Tung was asking about as Het DOOLHOF-SPEL, a game that has been in my collection for decades. I had always thought it was a Dutch game from the late nineteenth century, although the set I have is not dated and neither does it include any information about the publisher. After reading Mr. Tung's letter, I began to see Labyrinth in a completely different light.

Recent research by Rob van Linden (Historical Overview of Dutch Games, website no longer available) has given some insight into how the game entered the book. James Joyce bought a German version of the game, which was named “Labyrinth Spiel,” at the Franz Carl Weber Game-shop in Zürich, located in the Bahnhoffstrasse. Rumour has it that he thereafter played the game every evening with his daughter. Joyce's copy of Labyrinth is now exhibited by the James Joyce Society in Zürich.

Are we to suppose from Mr. Tung's letter that Joyce discerned six errors of judgement while playing Labyrinth with his daughter, and then these six errors of judgement somehow have correspondences in the section of Ulysses Joyce was writing at the time? Seeking clarification in 2011, I tried to trace Mr. Tung, but to no avail. By the way, I have played the game many times, but I have no Idea about those six errors of judgement.

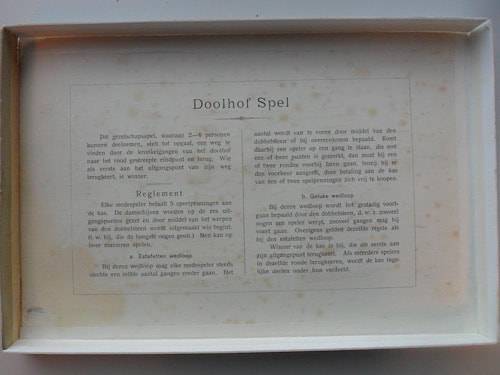

I do hope I made you curious about this game and its rules. See below the rules in Dutch, printed in the lid of the box.

Are we to suppose from Mr. Tung's letter that Joyce discerned six errors of judgement while playing Labyrinth with his daughter, and then these six errors of judgement somehow have correspondences in the section of Ulysses Joyce was writing at the time? Seeking clarification in 2011, I tried to trace Mr. Tung, but to no avail. By the way, I have played the game many times, but I have no Idea about those six errors of judgement.

I do hope I made you curious about this game and its rules. See below the rules in Dutch, printed in the lid of the box.

For your convenience I will do my best to translate the rules from old-fashioned Dutch into modern English:

Labyrinth Game

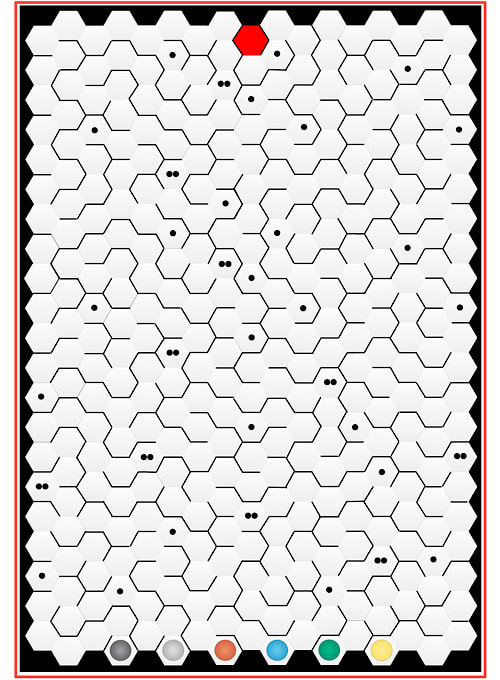

This party game, which 2-6 persons can take part of, has objective to find a route through the crooked paths of the labyrinth to the red endpoint and all the way back.

Whoever returns first at the starting point of his journey, becomes winner.

Regulations

Each player pays 5 game-tokens into the cashbox. The checker-discs are placed on the six starting-points and by throwing the die it is decided who begins. (That is, he, who throws the highest score.) There are two ways for play.

a. Relay race

In this race each player is only allowed to move [in his turn] the same number of [hexagonal] fields. The number is beforehand set by using the die or by agreement [between the players]. When a player ends his turn on a field, which is marked with one or two dots, then he has to pass for one or two turns, unless he prefers, by paying the cashbox one or two game-tokens, to redeem himself.

b. Luck race

In this race the steady movement forward is set by the die, that means, the number he throws gives the number of fields he can play forward. For the rest the same rules apply as for the relay race.

The winner of the cashbox is he who first returns at his starting-point. If more players in the same turn return, the cashbox is divided into equal parts among them.

When you want to play the game, use six different coloured pawns, one die, and a copy of the reconstructed Labyrinth board:

Fred Horn is a Dutch game player, collector, and developer. He is a specialist collector and scholar, particularly, of abstract games originating in the Netherlands. In 2007, the Stichting SP&L (Spellen, Puzzels & Ludotheek) was founded to manage his collection of over 10,000 items, and through this foundation in 2009 Fred donated his entire game collection to the Flemish Games Archive (Vlaams Spellenarchief) in Brugge, Belgium. At the moment, the whole collection is being sorted and documented. In addition, Fred has 30 published games, and many ideas waiting. In AG20 we plan to feature his game Fenix, which combines elements of Chess and Checkers in a fluid game of high strategic interest.

The original Labyrinth rules are sparse, and needed to be interpreted, with Fred's help. The main uncertainty is what happens when a token is moved to a one- or two-dot space, to the red goal space, or to a space occupied by an opponent's token. The interpretation below is chosen for consistency and to emphasize the possibility of blocking manoeuvres.

A curious story is associated with Labyrinth. John McCallion, interviewer of Kate Jones in this issue, and illustrious former Board Games Editor for Games magazine, sent me an email in which he asked about the letter concerning Labyrinth in AG15. I didn't think we ever received any further information, but I was just starting to check, when I received an email from Fred Horn, unsolicited and out of the blue, with the article above about Labyrinth. Fred and John swore they did not collaborate, and subsequently I introduced them to each other. The force of this coincidence was astounding. I knew then we had to write about Labyrinth in AG19, and await further developments. We are certainly very glad to provide a response to Mr. Tung, albeit 17 years later. I do hope this article somehow comes to his attention. ~ Ed.

The original Labyrinth rules are sparse, and needed to be interpreted, with Fred's help. The main uncertainty is what happens when a token is moved to a one- or two-dot space, to the red goal space, or to a space occupied by an opponent's token. The interpretation below is chosen for consistency and to emphasize the possibility of blocking manoeuvres.

- Before the game starts, each player pays five tokens into the cashbox.

- The game is playable with two to six players.

- The players each choose one of the six pieces, in any manner they like.

- A player's piece starts on the first line of the board on the space that has the same colour as the piece.

- For the "relay" version, the players pick a number between one and six (by choice or by rolling a die), and this number corresponds to the number of spaces a player moves her piece on each turn.

- For the "luck" version, each player rolls a die each turn before moving his piece to determine how many spaces she has to move.

- On a player's turn, the complete number of spaces specified must be utilized to move her piece, unless the piece reaches a one- or two-dot space, the red goal space, or a space containing an opponent's token; the piece must immediately stop moving in these three cases.

- After landing on a space with one or two dots, the player loses one or two turns, respectively.

- On the turn after landing on a space with one or two dots, a player can pay one or two tokens to the cash box, respectively, to unfree her piece. If the tokens are paid to the cash box, the player does not lose the one or two turns, respectively.

- A piece reaches the red goal space by finishing its turn in that space.

- After landing on an opponent's pieces, the opponent cannot move until after the player moves off the next turn.

- A player wins by getting her piece back to its home base, which does not have to be reached by exact count.

- The requirement that the contents of the cashbox is split if both players reach home in the same turn implies that the game was played in a series of turns, in which each player makes a move.

- The winner wins the contents of the cashbox, including the five tokens each player paid into it at the beginning of the game and any additional tokens paid into it by players to unfree pieces.

- The cashbox presumably was an instrument for gambling. However, it seems clear that Labyrinth plays perfectly well without gambling, as do games like Backgammon, for example. The players just have to keep track of tokens won and lost over a series of games.

A curious story is associated with Labyrinth. John McCallion, interviewer of Kate Jones in this issue, and illustrious former Board Games Editor for Games magazine, sent me an email in which he asked about the letter concerning Labyrinth in AG15. I didn't think we ever received any further information, but I was just starting to check, when I received an email from Fred Horn, unsolicited and out of the blue, with the article above about Labyrinth. Fred and John swore they did not collaborate, and subsequently I introduced them to each other. The force of this coincidence was astounding. I knew then we had to write about Labyrinth in AG19, and await further developments. We are certainly very glad to provide a response to Mr. Tung, albeit 17 years later. I do hope this article somehow comes to his attention. ~ Ed.

Next