Chess variants

Chess variants abound. David Pritchard's The Encyclopedia of Chess Variants (Games & Puzzles Publications, 1994) describes well over 1,000. A common theme that has attracted the attention even of world champion Chess players over the years is the extension of the orthodox game by increasing the size of the board to 10x8 or 10x10 with the addition of new pieces. The goal is often to overcome perceived deficiencies of the standard game, such as the prevalence of draws among high-ranked players.

Given that the Queen is a combination of Rook and Bishop (R+B), obvious choices for new pieces are to take the Knight's move and combine it with the power of Rook or Bishop. The 10x10 Grand Chess (Christian Freeling, 1984; AG3 and others) does just this, with the Marshall (R+N) and Cardinal (B+N). Grand Chess has antecedents utilizing just this solution going back centuries, including Carrera's Chess (Pietro Carrera, 1617), Bird's Chess (Henry Edward Bird, 1874), and Capablanca Chess (Jose Raul Capablanca, 1920's)—see David Pritchard's book. Gothic Chess (Ed Trice, 2000) is a more recent chess variant that uses R+N and B+N.

Other 10x10 chess variants have kept the basic chess army, although supplemented with quite different pieces. Omega Chess (Daniel MacDonald, 1992, AG8) is notable in this regard, with Champion and Wizard. Actually, the Omega Chess board contains 104 squares, with the addition of an extra square diagonally attached to each corner. The Wizards, with extended Knight's moves, start in these additional squares. The Champions can jump two squares in any direction or step one square orthogonally.

Grand Chess and Omega Chess stand out from many of their competitors because they were commercially produced games that attracted a following. Super Chess (Ed Ginsberg, 1976) is another large chess variant that was commercially produced. Super Chess, too, is played on a 10x10 board and retains the complete army of standard Chess. The two new pieces in Super Chess, the Cyclops and Archer, are not so powerful as the Marshall or Cardinal, but they are more unusual even than the Wizard or Champion of Omega Chess. In addition, two of the Pawns of Super Chess are replaced with more powerful foot soldiers called Super Pawns, or Deacons. Like Grand Chess and Omega Chess, Super Chess attracted a body of enthusiastic players, at least for a while.

The Super Chess opening setup is somewhat variable, in that the Deacons can be placed on any of the second row squares among the Pawns, and the Cyclops can face in any direction—the orientation of the Cyclops determines its move. The different opening setups make it more difficult for one player to gain an advantage through memorization of opening sequences, although the variability is not so extreme that one has to start from scratch every game when thinking about the opening. Moreover, the Cyclops and Archer both give rise to unusual tactics. Indeed, as we will show below, the Cyclops and Archer are ideally suited to breaking down positions to reach the enemy King. Perhaps it is this feature of Super Chess that has led to the very low proportion of draws among recorded games.

As mentioned above, Cyclops and Archer are less powerful than their Grand Chess equivalents, Marshal and Cardinal. Moreover, the Super Chess Rooks can be slower to enter the fray than in Grand Chess. These two factors mean that Super Chess has less of a “wild” feeling than is sometimes the case with Grand Chess—although I know that Christian Freeling was very deliberate in designing the powerful Grand Chess army, with its highly mobile Rooks. In addition, the Super Chess Pawns start on the second rank and retain the move from standard Chess, unlike in Grand Chess, whose Pawns start on the third rank, and unlike in Omega Chess, whose Pawns can move three squares forward initially. The Super Chess forces are thus slower to engage than either in Grand Chess or in Omega Chess. Nevertheless, the additional powers of the Deacons offer some flexibility and focus in the opening.

The eccentricity of games might refer to features of games that are creatively different and unusual. Rodney Frederickson's games Zhadu (AG11, AG17), Qyshinsu, and Karvilaj (the latter to be described in AG20) all exhibit high levels of eccentricity, which is one of the reasons I like them. The Onyx board design (AG4 and others) might well be described as eccentric, and the same is true of Push Fight (AG18 and this issue). Eccentricity implies uncommon or even completely original ludemes (see the interview with Cameron Browne in AG17). The Cyclops and Archer are certainly more eccentric than the Marshall and Cardinal of Grand Chess, and perhaps this is a good thing.

The variability of the Super Chess opening and the eccentric powers of Cyclops and Archer ensure that Super Chess stands out among the 10x10 chess variants that extend regular Chess. I do not claim that Super Chess is better than the other 10x10 chess variants, merely that it has its own unique character and that it is worthy of comparison with the finest of the genre.

Ed Ginsberg first developed Super Chess in 1976. His wife sculpted the new pieces, Cyclops and Archer, and in 1981 Ed's company, Super Chess Inc., produced 10,000 sets. He introduced Super Chess to kNights Of the Square Table (NOST), a prominent society for the play of abstract games by correspondence, and went to Chess tournaments to give sets to highly ranked players. The photograph below, for example, shows Ed giving a Super Chess set to former Chess World Champion Anatoly Karpov, in New York in 1990. After Karpov spoke supportively of the game in the mid-1980's, 3,000 sets were sold in the old Soviet Union, alone. Super Chess underwent extensive testing, with more than 1,500 games played, and it was among Games magazine’s top-ten strategy games for 1987. After the game caught on, Ed offered a US$1,000 prize to the winner of a Super Chess worldwide tournament played by correspondence—this was before the Internet, of course. The tournament had 64 players and it took three and a half years to complete. The final game of this tournament is annotated below.

When the 10,000 sets of the initial production run were sold, Ed did not manufacture more. Like many abstract games before and since, Super Chess fell into obscurity. However, Super Chess is historically significant among abstract games and is a very good game that deserves a second look.

In my presentation of Super Chess, below, much of the material comes from Ed Ginsberg's own writing on his game, although edited somewhat to fit the context of this article. Effectively, however, Ed is the co-author of this article.

Given that the Queen is a combination of Rook and Bishop (R+B), obvious choices for new pieces are to take the Knight's move and combine it with the power of Rook or Bishop. The 10x10 Grand Chess (Christian Freeling, 1984; AG3 and others) does just this, with the Marshall (R+N) and Cardinal (B+N). Grand Chess has antecedents utilizing just this solution going back centuries, including Carrera's Chess (Pietro Carrera, 1617), Bird's Chess (Henry Edward Bird, 1874), and Capablanca Chess (Jose Raul Capablanca, 1920's)—see David Pritchard's book. Gothic Chess (Ed Trice, 2000) is a more recent chess variant that uses R+N and B+N.

Other 10x10 chess variants have kept the basic chess army, although supplemented with quite different pieces. Omega Chess (Daniel MacDonald, 1992, AG8) is notable in this regard, with Champion and Wizard. Actually, the Omega Chess board contains 104 squares, with the addition of an extra square diagonally attached to each corner. The Wizards, with extended Knight's moves, start in these additional squares. The Champions can jump two squares in any direction or step one square orthogonally.

Grand Chess and Omega Chess stand out from many of their competitors because they were commercially produced games that attracted a following. Super Chess (Ed Ginsberg, 1976) is another large chess variant that was commercially produced. Super Chess, too, is played on a 10x10 board and retains the complete army of standard Chess. The two new pieces in Super Chess, the Cyclops and Archer, are not so powerful as the Marshall or Cardinal, but they are more unusual even than the Wizard or Champion of Omega Chess. In addition, two of the Pawns of Super Chess are replaced with more powerful foot soldiers called Super Pawns, or Deacons. Like Grand Chess and Omega Chess, Super Chess attracted a body of enthusiastic players, at least for a while.

The Super Chess opening setup is somewhat variable, in that the Deacons can be placed on any of the second row squares among the Pawns, and the Cyclops can face in any direction—the orientation of the Cyclops determines its move. The different opening setups make it more difficult for one player to gain an advantage through memorization of opening sequences, although the variability is not so extreme that one has to start from scratch every game when thinking about the opening. Moreover, the Cyclops and Archer both give rise to unusual tactics. Indeed, as we will show below, the Cyclops and Archer are ideally suited to breaking down positions to reach the enemy King. Perhaps it is this feature of Super Chess that has led to the very low proportion of draws among recorded games.

As mentioned above, Cyclops and Archer are less powerful than their Grand Chess equivalents, Marshal and Cardinal. Moreover, the Super Chess Rooks can be slower to enter the fray than in Grand Chess. These two factors mean that Super Chess has less of a “wild” feeling than is sometimes the case with Grand Chess—although I know that Christian Freeling was very deliberate in designing the powerful Grand Chess army, with its highly mobile Rooks. In addition, the Super Chess Pawns start on the second rank and retain the move from standard Chess, unlike in Grand Chess, whose Pawns start on the third rank, and unlike in Omega Chess, whose Pawns can move three squares forward initially. The Super Chess forces are thus slower to engage than either in Grand Chess or in Omega Chess. Nevertheless, the additional powers of the Deacons offer some flexibility and focus in the opening.

The eccentricity of games might refer to features of games that are creatively different and unusual. Rodney Frederickson's games Zhadu (AG11, AG17), Qyshinsu, and Karvilaj (the latter to be described in AG20) all exhibit high levels of eccentricity, which is one of the reasons I like them. The Onyx board design (AG4 and others) might well be described as eccentric, and the same is true of Push Fight (AG18 and this issue). Eccentricity implies uncommon or even completely original ludemes (see the interview with Cameron Browne in AG17). The Cyclops and Archer are certainly more eccentric than the Marshall and Cardinal of Grand Chess, and perhaps this is a good thing.

The variability of the Super Chess opening and the eccentric powers of Cyclops and Archer ensure that Super Chess stands out among the 10x10 chess variants that extend regular Chess. I do not claim that Super Chess is better than the other 10x10 chess variants, merely that it has its own unique character and that it is worthy of comparison with the finest of the genre.

Ed Ginsberg first developed Super Chess in 1976. His wife sculpted the new pieces, Cyclops and Archer, and in 1981 Ed's company, Super Chess Inc., produced 10,000 sets. He introduced Super Chess to kNights Of the Square Table (NOST), a prominent society for the play of abstract games by correspondence, and went to Chess tournaments to give sets to highly ranked players. The photograph below, for example, shows Ed giving a Super Chess set to former Chess World Champion Anatoly Karpov, in New York in 1990. After Karpov spoke supportively of the game in the mid-1980's, 3,000 sets were sold in the old Soviet Union, alone. Super Chess underwent extensive testing, with more than 1,500 games played, and it was among Games magazine’s top-ten strategy games for 1987. After the game caught on, Ed offered a US$1,000 prize to the winner of a Super Chess worldwide tournament played by correspondence—this was before the Internet, of course. The tournament had 64 players and it took three and a half years to complete. The final game of this tournament is annotated below.

When the 10,000 sets of the initial production run were sold, Ed did not manufacture more. Like many abstract games before and since, Super Chess fell into obscurity. However, Super Chess is historically significant among abstract games and is a very good game that deserves a second look.

In my presentation of Super Chess, below, much of the material comes from Ed Ginsberg's own writing on his game, although edited somewhat to fit the context of this article. Effectively, however, Ed is the co-author of this article.

Rules

(Based on the Second Edition rules, with some edits.)

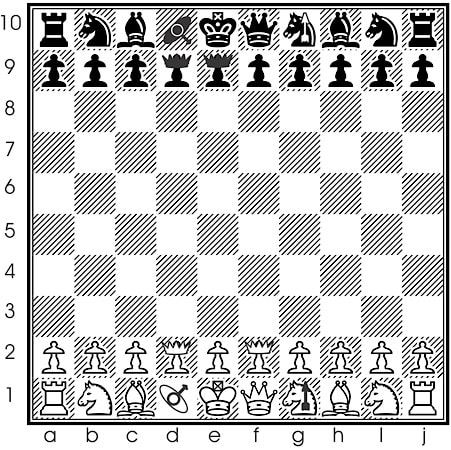

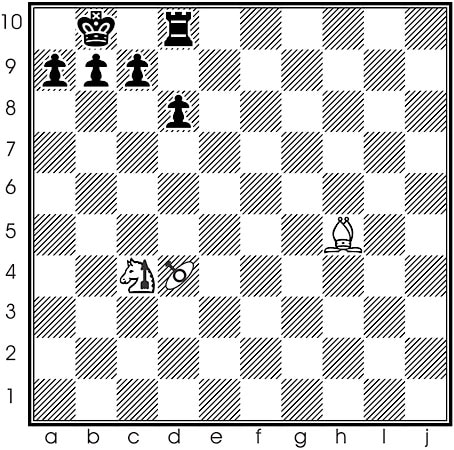

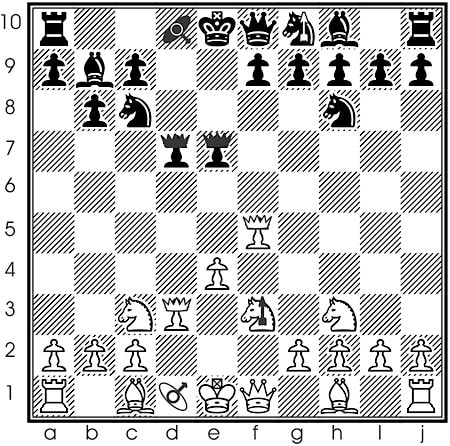

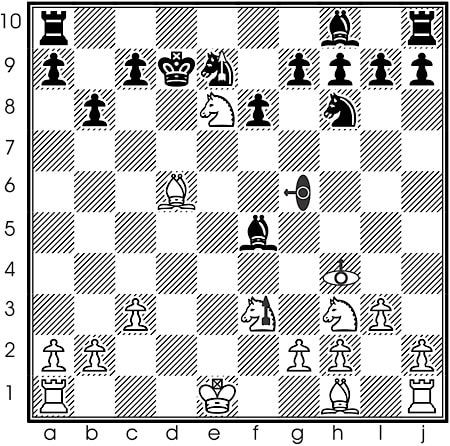

Super Chess is played on a 10x10 checkered board with a regular Chess set, with the addition on each side of one Cyclops, one Archer, and two Super Pawns, or Deacons. I will usually refer to the Super Pawns as Deacons, because then they need just a "D" for notation—and also I prefer the name! Diagram 1 gives one possible starting position. The piece represented by the eye is the Cyclops, the one-eyed creature of legend. It must always be oriented in one of the eight directions, as shown by the arrow. The Knight with the arrow is the Archer, and the Pawns with the spiky caps are Deacons.

To set up, the players first place their pieces on the back ranks. White chooses an initial orientation for the Cyclops, and then Black orientates her Cyclops. Then White chooses two positions on the second rank to place her Deacons, and Black follows by choosing two positions on the ninth rank for her Deacons. Set up is completed by filling in the remaining positions with Pawns on the respective ranks. Allowing Black to follow White in choosing the variable set-up is designed to equalize White’s advantage of the first move.

(Based on the Second Edition rules, with some edits.)

Super Chess is played on a 10x10 checkered board with a regular Chess set, with the addition on each side of one Cyclops, one Archer, and two Super Pawns, or Deacons. I will usually refer to the Super Pawns as Deacons, because then they need just a "D" for notation—and also I prefer the name! Diagram 1 gives one possible starting position. The piece represented by the eye is the Cyclops, the one-eyed creature of legend. It must always be oriented in one of the eight directions, as shown by the arrow. The Knight with the arrow is the Archer, and the Pawns with the spiky caps are Deacons.

To set up, the players first place their pieces on the back ranks. White chooses an initial orientation for the Cyclops, and then Black orientates her Cyclops. Then White chooses two positions on the second rank to place her Deacons, and Black follows by choosing two positions on the ninth rank for her Deacons. Set up is completed by filling in the remaining positions with Pawns on the respective ranks. Allowing Black to follow White in choosing the variable set-up is designed to equalize White’s advantage of the first move.

The rules are those of orthodox Chess except for the following:

Cyclops

The Cyclops can move one, two, or three squares in the direction of its orientation. Any enemy pieces on squares it moves over or lands on are captured, but it can move over friendly pieces without damaging them. Alternatively, the Cyclops can make a “blind retreat” up to three squares in a direction directly opposite to its orientation. In this case, however, all pieces are captured, friendly or enemy, on the squares it moves over or lands on. (When moving forward, the Cyclops cannot finish its move on a square occupied by a friendly piece, but there is nothing to stop it doing so when making a blind retreat.) After locating to its new square the Cyclops’ movement is completed by choosing a new orientation, if so desired. The Cyclops can rotate to a new direction on its original square without relocating to another square, and this is counted as a complete move. Note that the Cyclops cannot simply rotate in a complete circle, effectively allowing a player to pass a turn.

The value of the Cyclops is estimated at 4 points (compared with standard values associated with Chess pieces).

Archer

The Archer moves and captures like a Chess Knight. Alternatively, the Archer may capture without moving: an enemy piece exactly four squares from the Archer in an orthogonal direction is simply removed from play, and this counts as a complete move for the Archer. It does not matter whether there are friendly or enemy pieces interposed between the Archer and the piece it is capturing in this manner. (Note that the arrow on the Archer in the diagrams is for identification only—the Archer is not orientable like the Cyclops.)

The value of the Archer is estimated at 4 points.

Cyclops

The Cyclops can move one, two, or three squares in the direction of its orientation. Any enemy pieces on squares it moves over or lands on are captured, but it can move over friendly pieces without damaging them. Alternatively, the Cyclops can make a “blind retreat” up to three squares in a direction directly opposite to its orientation. In this case, however, all pieces are captured, friendly or enemy, on the squares it moves over or lands on. (When moving forward, the Cyclops cannot finish its move on a square occupied by a friendly piece, but there is nothing to stop it doing so when making a blind retreat.) After locating to its new square the Cyclops’ movement is completed by choosing a new orientation, if so desired. The Cyclops can rotate to a new direction on its original square without relocating to another square, and this is counted as a complete move. Note that the Cyclops cannot simply rotate in a complete circle, effectively allowing a player to pass a turn.

The value of the Cyclops is estimated at 4 points (compared with standard values associated with Chess pieces).

Archer

The Archer moves and captures like a Chess Knight. Alternatively, the Archer may capture without moving: an enemy piece exactly four squares from the Archer in an orthogonal direction is simply removed from play, and this counts as a complete move for the Archer. It does not matter whether there are friendly or enemy pieces interposed between the Archer and the piece it is capturing in this manner. (Note that the arrow on the Archer in the diagrams is for identification only—the Archer is not orientable like the Cyclops.)

The value of the Archer is estimated at 4 points.

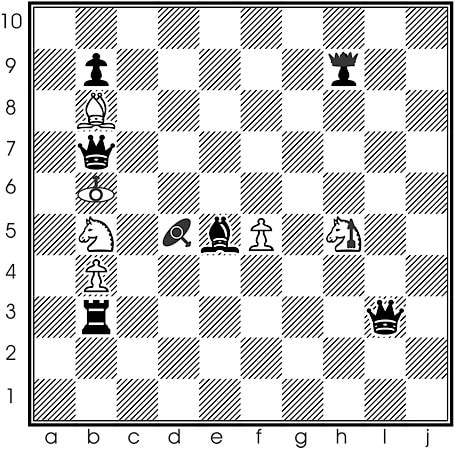

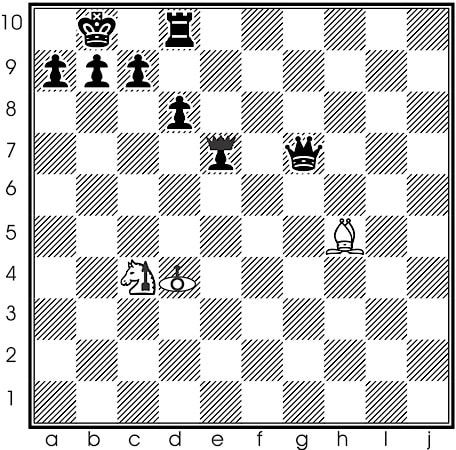

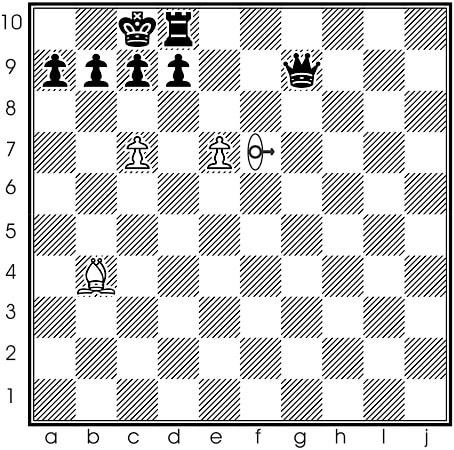

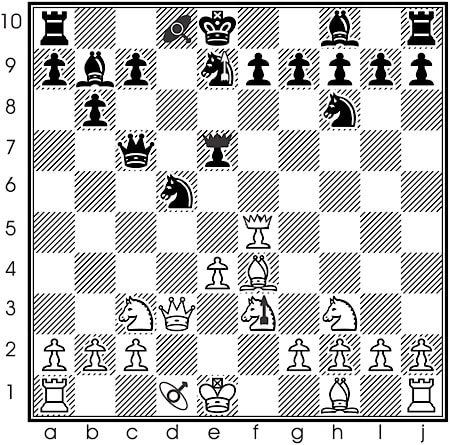

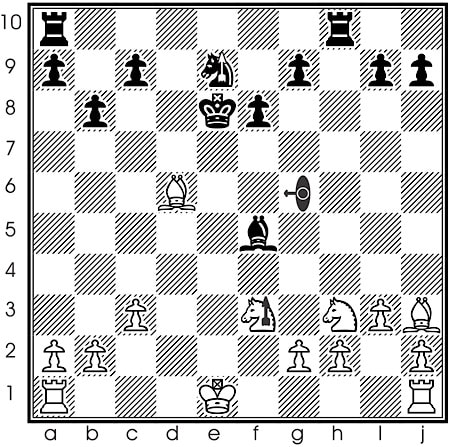

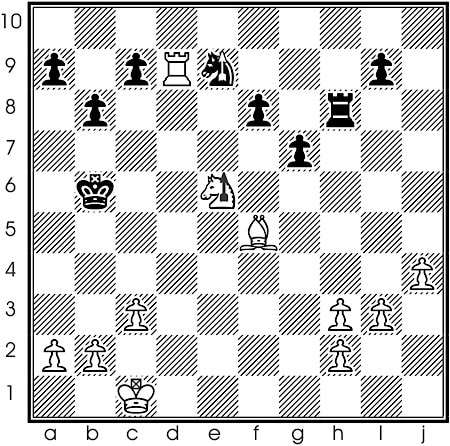

In Diagram 2, the white Cyclops on b6 can move to b7 capturing the black Queen; or it can move to b9, capturing the black Pawn as well as the Queen, but jumping over the white Bishop on b8. The white Cyclops could also make a “blind retreat” and capture the black Rook on b2, but in this case both the white Pawn and white Knight would also be removed from play. The white Archer on h5 can capture the Cyclops on d5 or the Deacon on h9, without moving. On the other hand, the Archer could simply move like a Knight and capture the Queen on i3.

Deacon

The Deacon behaves exactly like a regular Pawn, except for additional features:

The en passant rules are applicable to Deacons. Thus, Deacons can capture or be captured en passant by regular Pawns or other Deacons. A Deacon can use its extra power when capturing en passant. On the other hand, if a Deacon makes a two space leap over an occupied square, then it is immune from capture by en passant.

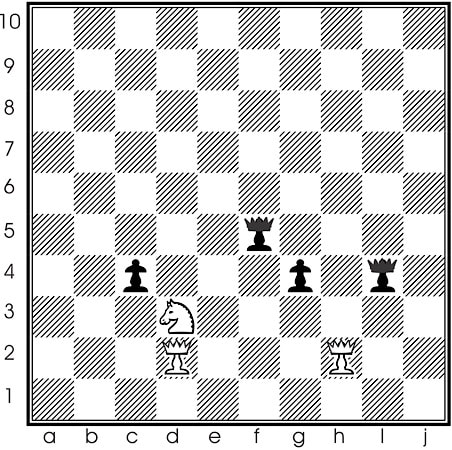

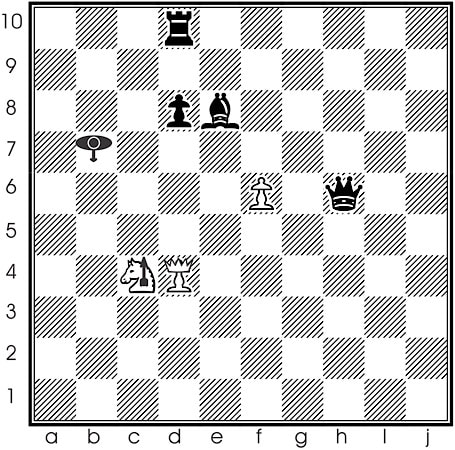

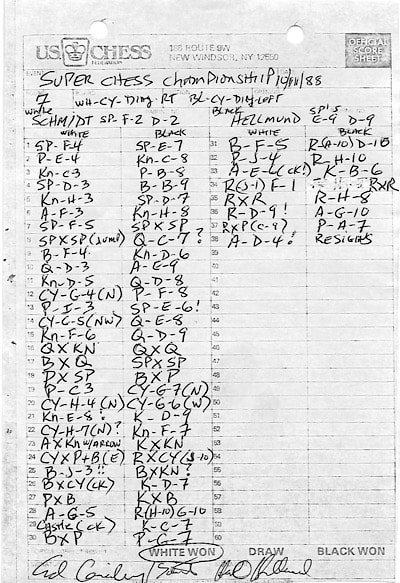

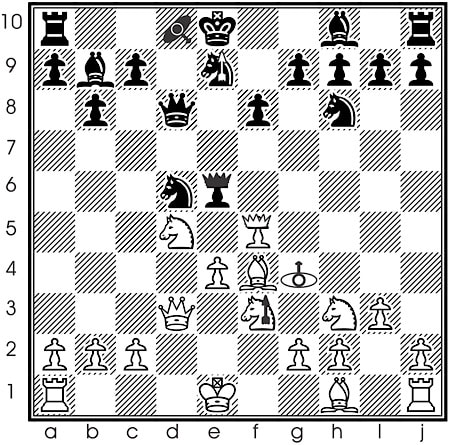

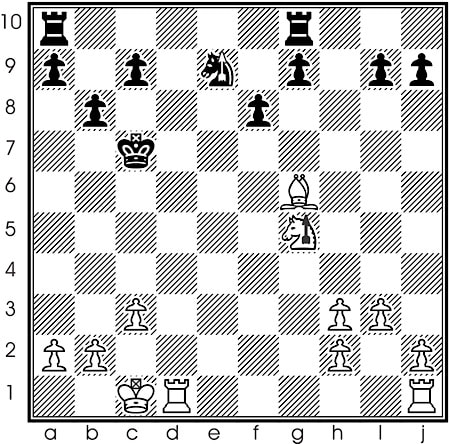

In Diagram 3, if White moves the Deacon to d4, then Black cannot capture en passant either with the Pawn or Deacon. On the other hand, if White moves the Deacon to h4, Black can capture en passant with either of the two Deacons or the Pawn by moving to h3.

The value of the Deacon is estimated at 2 points.

Promotion

Pawns and Deacons promote upon reaching the opponent’s back rank. Promotion may be to any piece except a Pawn, Deacon, or King.

Castling

The regular Orthodox Chess rules of castling apply, except for some necessary clarifications: on the King’s side the King moves to the King’s Bishop position, and the Rook moves to the Cyclops position; on the Queen’s side the King moves to the Queen’s Bishop position and the Rook moves to the Archer position.

Deacon

The Deacon behaves exactly like a regular Pawn, except for additional features:

- On a Deacon’s initial move of two squares directly forward, it does not matter if the first square is occupied, whether by a friendly piece or an enemy piece. Enemy pieces jumped over are not captured, and of course the square moved to must be vacant.

- A Deacon can capture on a square that is either one or two spaces away diagonally forward. When capturing two squares away, it does not matter if the first square diagonally forward is occupied, whether by a friendly piece or an enemy piece. Again, enemy pieces jumped over are not captured.

The en passant rules are applicable to Deacons. Thus, Deacons can capture or be captured en passant by regular Pawns or other Deacons. A Deacon can use its extra power when capturing en passant. On the other hand, if a Deacon makes a two space leap over an occupied square, then it is immune from capture by en passant.

In Diagram 3, if White moves the Deacon to d4, then Black cannot capture en passant either with the Pawn or Deacon. On the other hand, if White moves the Deacon to h4, Black can capture en passant with either of the two Deacons or the Pawn by moving to h3.

The value of the Deacon is estimated at 2 points.

Promotion

Pawns and Deacons promote upon reaching the opponent’s back rank. Promotion may be to any piece except a Pawn, Deacon, or King.

Castling

The regular Orthodox Chess rules of castling apply, except for some necessary clarifications: on the King’s side the King moves to the King’s Bishop position, and the Rook moves to the Cyclops position; on the Queen’s side the King moves to the Queen’s Bishop position and the Rook moves to the Archer position.

Strategic hints

(Based on the Chess Variants file, with some edits.)

Black should take some care in placing the two Deacons since that placement somewhat offsets White's advantage in moving first.

The true power of the Cyclops or the Archer will appear only after much experience, but some suggestions about strength may be made. In Chess, Knight and Bishop are considered equal and readily exchanged for each other. On the larger board of Super Chess the Bishop has greater mobility and, consequently, greater value. It should not be exchanged for a Knight without significant gain in position or other material. The Archer is somewhat more powerful than the Knight, but the full usefulness of its arrow requires that it stay near the centre of the board. For instance, King and Archer cannot mate a lone King, the Archer being no more effective in this respect than is a Knight. The Archer might be more or less valuable than a Bishop, depending upon the position.

The Cyclops is probably more powerful than a Bishop, though not as strong as a Rook. A mating position is possible for King and Cyclops against the lone King, but it cannot be reached unless the defender makes errors, unlike King and Rook which can force mate against a King. The Cyclops is valuable in crowded positions where it can make multiple captures and open lines.

Here are a few illustrations to give you an idea or two about Cyclops and Archer.

A possible starting position is shown in Diagram 1. (Remember, the Deacons can be placed differently than shown, and either Cyclops is allowed to face in some other direction.) To record the moves, C is used for Cyclops, A for Archer, and D for Deacon. In parentheses after the Cyclops move will be a compass label (NE, S, SW, etc.) to indicate the direction it faces at the end of its move. North is always the direction facing away from White, so that a black Cyclops facing directly down the board towards White is C(S), for example.

To start off, either Cyclops or Archer can mate from the starting position in three moves.

For the Cyclops, for example, Cg4(NW)-Ce6(N)-Ce7(N)++ or Cf3(NW)-Ce4(N)-Ce7(N)++.

For the Archer, for example, Af3-Ag5-Ae6++.

It is important to realize that these are not good ways to open play, being easily countered, but are just included to show how the pieces can be used. They do lead to a more worthwhile observation, too.

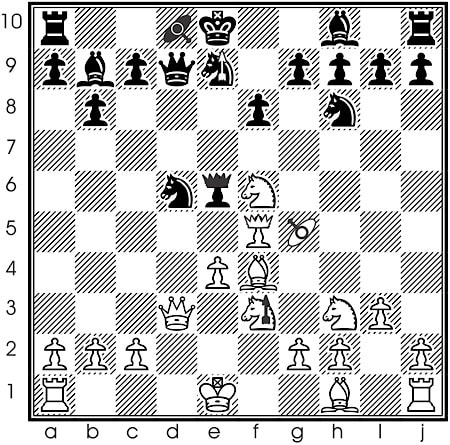

In Chess, castling is used to get the King safely behind a wall of unmoved Pawns. Often the plan of a game is to break through that wall to reach the King. In Super Chess, the Archer can shoot over the wall and the Cyclops can crash right through it, so castling does not provide as much safety as it does in Chess. Look at the position in Diagram 4. Play proceeds, 1.Ab6+ Ka10, 2.Ca7(N)++.

(Based on the Chess Variants file, with some edits.)

Black should take some care in placing the two Deacons since that placement somewhat offsets White's advantage in moving first.

The true power of the Cyclops or the Archer will appear only after much experience, but some suggestions about strength may be made. In Chess, Knight and Bishop are considered equal and readily exchanged for each other. On the larger board of Super Chess the Bishop has greater mobility and, consequently, greater value. It should not be exchanged for a Knight without significant gain in position or other material. The Archer is somewhat more powerful than the Knight, but the full usefulness of its arrow requires that it stay near the centre of the board. For instance, King and Archer cannot mate a lone King, the Archer being no more effective in this respect than is a Knight. The Archer might be more or less valuable than a Bishop, depending upon the position.

The Cyclops is probably more powerful than a Bishop, though not as strong as a Rook. A mating position is possible for King and Cyclops against the lone King, but it cannot be reached unless the defender makes errors, unlike King and Rook which can force mate against a King. The Cyclops is valuable in crowded positions where it can make multiple captures and open lines.

Here are a few illustrations to give you an idea or two about Cyclops and Archer.

A possible starting position is shown in Diagram 1. (Remember, the Deacons can be placed differently than shown, and either Cyclops is allowed to face in some other direction.) To record the moves, C is used for Cyclops, A for Archer, and D for Deacon. In parentheses after the Cyclops move will be a compass label (NE, S, SW, etc.) to indicate the direction it faces at the end of its move. North is always the direction facing away from White, so that a black Cyclops facing directly down the board towards White is C(S), for example.

To start off, either Cyclops or Archer can mate from the starting position in three moves.

For the Cyclops, for example, Cg4(NW)-Ce6(N)-Ce7(N)++ or Cf3(NW)-Ce4(N)-Ce7(N)++.

For the Archer, for example, Af3-Ag5-Ae6++.

It is important to realize that these are not good ways to open play, being easily countered, but are just included to show how the pieces can be used. They do lead to a more worthwhile observation, too.

In Chess, castling is used to get the King safely behind a wall of unmoved Pawns. Often the plan of a game is to break through that wall to reach the King. In Super Chess, the Archer can shoot over the wall and the Cyclops can crash right through it, so castling does not provide as much safety as it does in Chess. Look at the position in Diagram 4. Play proceeds, 1.Ab6+ Ka10, 2.Ca7(N)++.

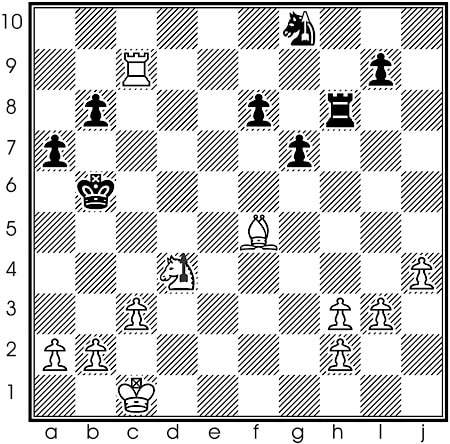

Diagram 5 shows a more complicated version of the same idea. This time, 1.Ab6+ Ka10, 2.Cd7(W). Black's Queen (and Deacon) is threatened, but if she moves to escape, 3.Ca7(N)++, so the Queen falls.

These examples suggest that the King in Super Chess needs more escape squares around him than he usually has in Chess.

The Knight fork is a powerful tool in a Chess player's arsenal. The Archer, by combining that fork with arrow attacks, can be exceedingly dangerous. The position in Diagram 6 is not likely to appear in an actual game, but something like it is worth watching for. The move Ad6 places Black's Queen, Rook, Bishop, and Cyclops all under attack at once. Unless Black has strong counter-attacks, White will win at least two pieces. The Archer seems to be a good piece to save for the middle game and later. Important defensive pieces can be attacked from a distance, making it harder to maintain a good position.

These examples suggest that the King in Super Chess needs more escape squares around him than he usually has in Chess.

The Knight fork is a powerful tool in a Chess player's arsenal. The Archer, by combining that fork with arrow attacks, can be exceedingly dangerous. The position in Diagram 6 is not likely to appear in an actual game, but something like it is worth watching for. The move Ad6 places Black's Queen, Rook, Bishop, and Cyclops all under attack at once. Unless Black has strong counter-attacks, White will win at least two pieces. The Archer seems to be a good piece to save for the middle game and later. Important defensive pieces can be attacked from a distance, making it harder to maintain a good position.

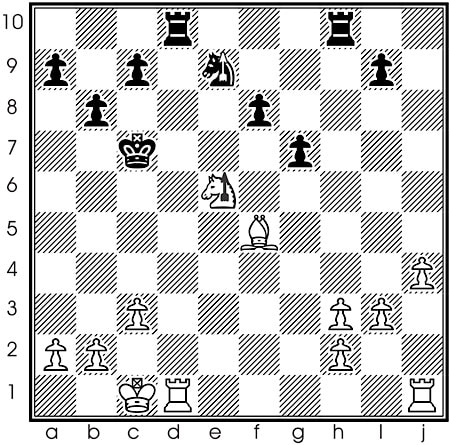

Diagram 7 shows a position in which the Pawn at g9 is important to Black's Pawn structure and the defence of his King. The move Ag5 leaves no hope for saving it.

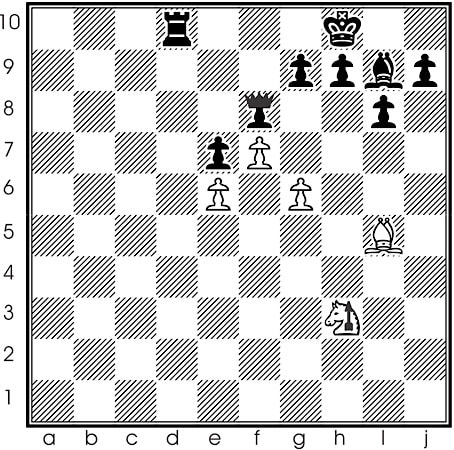

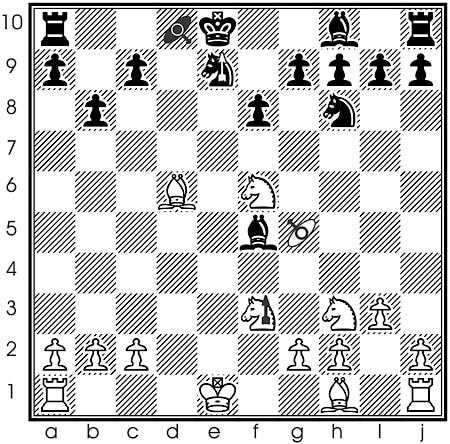

The blind retreat of the Cyclops, which sometimes destroys one's own pieces, seems to be more of a move to avoid, but it can be used as a powerful attacking tool. It may happen that a player's pieces, especially Pawns, can block lines of attack. The Cyclops can be used to get them out of the way. In Diagram 8, White moves Cxe7xc7(N)+. While Black is getting his King out of check, White has the opportunity to take Black's Queen with the Bishop.

The blind retreat of the Cyclops, which sometimes destroys one's own pieces, seems to be more of a move to avoid, but it can be used as a powerful attacking tool. It may happen that a player's pieces, especially Pawns, can block lines of attack. The Cyclops can be used to get them out of the way. In Diagram 8, White moves Cxe7xc7(N)+. While Black is getting his King out of check, White has the opportunity to take Black's Queen with the Bishop.

Diagram 9 shows a different version of the same idea. Again, White starts with a blind retreat, clearing out the two Pawns which block his attacking Rook and Bishop. 1.Cxe7xc7(N)+ Kb10, 2.Cxc9,c10(W)++. It will be interesting to see how combinations such as these come out of actual games.

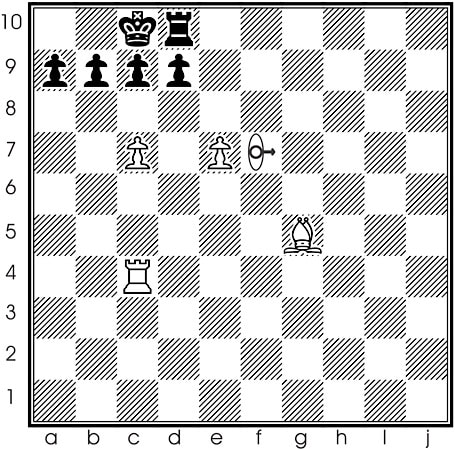

Championship Final Game

The Super Chess correspondence tournament ran for three and a half years, from 1985 to 1988, as players sent moves back and forth by regular mail. Here is the annotated game of the final match for the US$1,000 prize. Henry Schmidt from Germany played White; Henk Hellmund from the Netherlands played Black.

There are some inaccuracies in the play of the game, as you will see. Nevertheless, we reproduce it here for its historical significance in the world of chess variants, and for the way that it illustrates some tactics involving the unique Super Chess pieces, Cyclops, Archer, and Deacon. The annotations "!" and "?" are original, and any other commentary is new.

Championship Final Game

The Super Chess correspondence tournament ran for three and a half years, from 1985 to 1988, as players sent moves back and forth by regular mail. Here is the annotated game of the final match for the US$1,000 prize. Henry Schmidt from Germany played White; Henk Hellmund from the Netherlands played Black.

There are some inaccuracies in the play of the game, as you will see. Nevertheless, we reproduce it here for its historical significance in the world of chess variants, and for the way that it illustrates some tactics involving the unique Super Chess pieces, Cyclops, Archer, and Deacon. The annotations "!" and "?" are original, and any other commentary is new.

White: Henry Schmidt (Germany); Black: Henk Hellmund (Netherlands)

White: C(NE); Black: C(SE)

White: Dd2, Df2; Black: Dd9, De9

(Diagram 1)

White: C(NE); Black: C(SE)

White: Dd2, Df2; Black: Dd9, De9

(Diagram 1)

1.Df4 De7, 2.Pe4 Nc8, 3.Nc3 Pb8, 4.Dd3 Bb9, 5.Nh3 Dd7, 6.Af3 Nh8, 7.Df5 (Diagram 10).

7....Dxf5, 8.Dxf5 Qc7? (Black brings out the Queen too early), 9.Bf4 Nd6, 10.Qd3 Ae9 (Diagram 11) 11.Nd5 Qd8, 12.Cg4(N) Pf8, 13.Pi3 De6! (Diagram 12).

14.Cg5(NW) Qe8, 15.Nf6 Qd9 (Diagram 13--White continues to chase Black's Queen around), 16.Qxd6 Qxd6,17.Bxd6 Dxf5, 18.Pxf5 Bxf5 (Diagram 14).

19.Pc3 Cg7(S), 20.Ch4(N) Cg6(W), 21.Ne8! Kd9 (Diagram 15) 22.Ch7(N)? Nf7 (So that White must use two moves not one to capture N and B), 23.Axf7 Kxe8, 24.Cxh9xh10(E) R(j10)xh10, 25.Bj3!! (Diagram 16—White pins the black Cyclops).

25....Bxh3?, 26.Bxg6+ Kd7, 27.Pxh3 Kxd6, 28.Ag5 R(h10)g10 (Defending against Axg9), 29. 0-0+ Kc7 (Diagram 17), 30.Bxj9 Pg7, 31.Bf5 R(a10)d10, 32.Pj4 Rh10, 33.Ae6+! (Diagram 18).

33....Kb6, 34.R(j1)f1 Rxd1, 35.Rxd1 Rh8, 36.Rd9! (Diagram 19) Ag10, 37.Rxc9 Pa7, 38.Ad4! Resigns (Diagram 20—Black has no attack, he is a Bishop and two Pawns down, and his King is in mortal danger.)

Acknowledgements

It was my good fortune to get a Super Chess set from NOST in 2003. I subsequently wrote the original version of this article, which would have gone into the old AG17. The current version of the article was produced following a number of communications with Ed Ginsberg himself, and I thank him for the permission to reproduce here some of his material about Super Chess. Over the succeeding years since 2003, my set disappeared, and for planning this article now I tried to acquire another copy. Fortunately, one of my old NOST friends, John McCallion (see the interview with Kate Jones in this issue), came through, and his friend Drew Davidson very kindly donated a Super Chess set to Abstract Games. Thank you very much to both John and Drew!

We would be very interested to hear from readers about other chess variants that are worthy of saving from oblivion—modern or historical. Perhaps a game that has eccentric elements....

It was my good fortune to get a Super Chess set from NOST in 2003. I subsequently wrote the original version of this article, which would have gone into the old AG17. The current version of the article was produced following a number of communications with Ed Ginsberg himself, and I thank him for the permission to reproduce here some of his material about Super Chess. Over the succeeding years since 2003, my set disappeared, and for planning this article now I tried to acquire another copy. Fortunately, one of my old NOST friends, John McCallion (see the interview with Kate Jones in this issue), came through, and his friend Drew Davidson very kindly donated a Super Chess set to Abstract Games. Thank you very much to both John and Drew!

We would be very interested to hear from readers about other chess variants that are worthy of saving from oblivion—modern or historical. Perhaps a game that has eccentric elements....