Strategic analysis

Push Fight is an excellent modern abstract designed by Brett Picotte in 1980. Somewhere between Arimaa and Abalone, it is a game which manages to generate considerable intrigue from a very simple set of rules. In this piece we will explore some of the basic tactical patterns and strategic principles in the game.

Rules

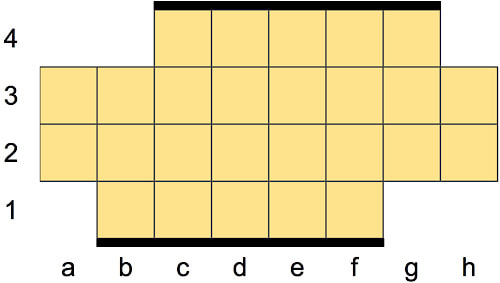

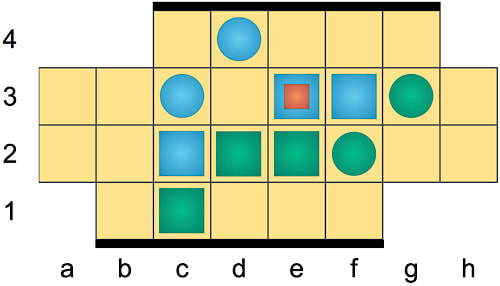

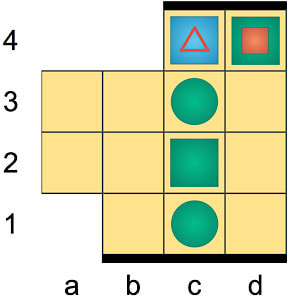

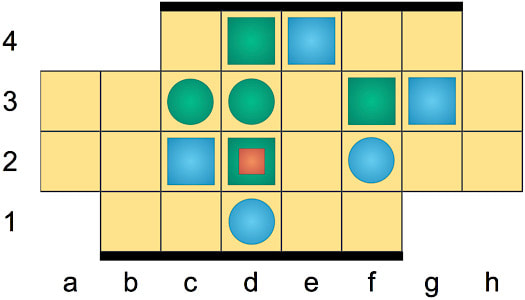

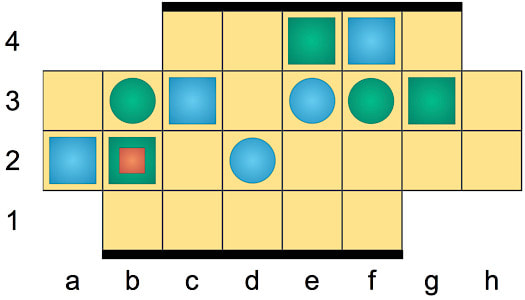

Push Fight is played on an irregularly shaped square grid, as pictured below. Along the top and bottom edges of the board are placed siderails, which are shown as thickened lines in the diagram. Each player owns three square pieces and two circular pieces of her own colour. There is also a neutral piece, called the anchor, which can rest on the square-shaped pieces.

Rules

Push Fight is played on an irregularly shaped square grid, as pictured below. Along the top and bottom edges of the board are placed siderails, which are shown as thickened lines in the diagram. Each player owns three square pieces and two circular pieces of her own colour. There is also a neutral piece, called the anchor, which can rest on the square-shaped pieces.

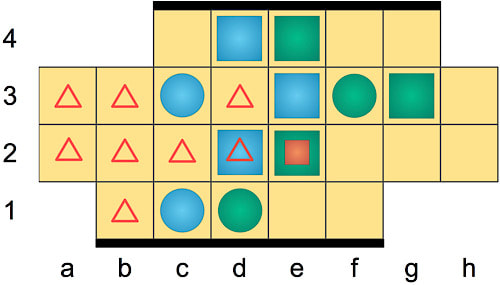

Setup: Initially, the board is empty. Blue (often White in physical sets) begins by placing her five pieces on the left half of the board (columns a through d) however she likes. Then, Green (often Black in physical sets) does the same with the right half of the board (columns e through h).

After the initial setup, each turn consists of the following two phases, in order:

1) Movement: Up to two times, a player may move one of their pieces. A move consists of a player selecting one of her five pieces, and sliding that piece to an orthogonally adjacent empty square any number of times. Note that movement is optional: a player can move 0, 1, or 2 pieces in any given turn.

2) Push: To end the turn, a player must execute a push with one of her three squares. Pushes can only be executed by squares and can only be done in the four cardinal directions. A push is possible if:

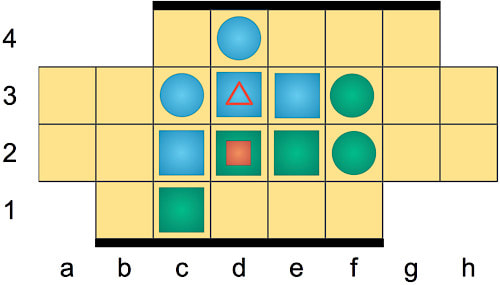

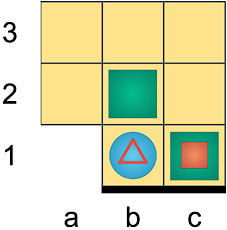

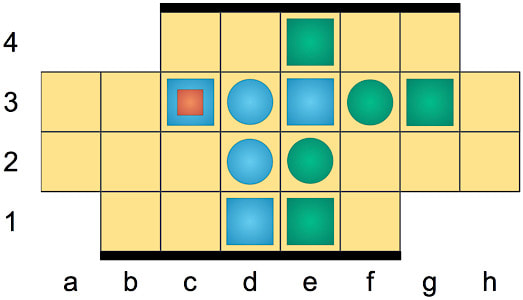

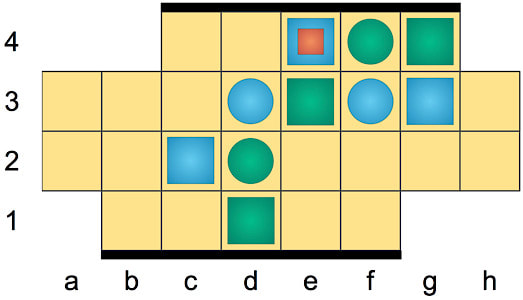

In particular, it is not possible to make a push which would send a piece through the siderail. Diagram 2 below demonstrates legal moves and pushes. Diagram 2a shows all legal moves of the d2 square. In Diagram 2b, Blue's d3 piece could push to the left or to the right, but not up (because of the siderail) nor down (because of the anchor). The result of a rightward push is shown in Diagram 2c.

After the initial setup, each turn consists of the following two phases, in order:

1) Movement: Up to two times, a player may move one of their pieces. A move consists of a player selecting one of her five pieces, and sliding that piece to an orthogonally adjacent empty square any number of times. Note that movement is optional: a player can move 0, 1, or 2 pieces in any given turn.

2) Push: To end the turn, a player must execute a push with one of her three squares. Pushes can only be executed by squares and can only be done in the four cardinal directions. A push is possible if:

- The immediate neighbour of the chosen square in the chosen direction is nonempty, and

- The line of pieces immediately in that direction terminates either in an empty space or a space off the board, and none of the pieces in that line hold the anchor.

In particular, it is not possible to make a push which would send a piece through the siderail. Diagram 2 below demonstrates legal moves and pushes. Diagram 2a shows all legal moves of the d2 square. In Diagram 2b, Blue's d3 piece could push to the left or to the right, but not up (because of the siderail) nor down (because of the anchor). The result of a rightward push is shown in Diagram 2c.

Goal: The first player to have one of their pieces pushed off the edge loses, and the other player is declared the winner.

A quick note on terminology: we call the squares b1, g4 the strong corners and c4, f1 the weak corners. The strategic distinction between the two will be examined later. Also, one advantage of the anchor mechanics is that it is easy to tell which side has the move in a given position. Namely, it is Blue to play if Green has the anchor, and vice versa.

Traps

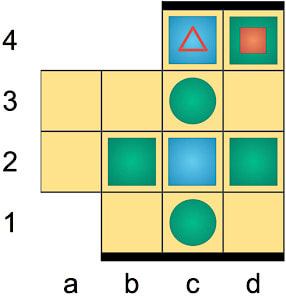

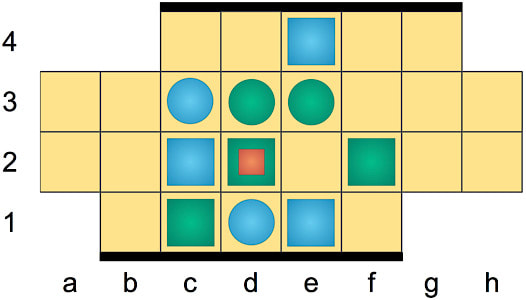

Traps in Push Fight are the equivalent of mating patterns in Chess. They are arrangements of pieces which signal unavoidable doom for the opponent. This game’s sole win condition is pushing an opponent’s piece off the edge, so recognizing these traps (and avoiding falling into them!) is essential to playing the game well. Since circles cannot execute pushes, they are more vulnerable to being trapped. Below are pictured several common examples of circle traps.

A quick note on terminology: we call the squares b1, g4 the strong corners and c4, f1 the weak corners. The strategic distinction between the two will be examined later. Also, one advantage of the anchor mechanics is that it is easy to tell which side has the move in a given position. Namely, it is Blue to play if Green has the anchor, and vice versa.

Traps

Traps in Push Fight are the equivalent of mating patterns in Chess. They are arrangements of pieces which signal unavoidable doom for the opponent. This game’s sole win condition is pushing an opponent’s piece off the edge, so recognizing these traps (and avoiding falling into them!) is essential to playing the game well. Since circles cannot execute pushes, they are more vulnerable to being trapped. Below are pictured several common examples of circle traps.

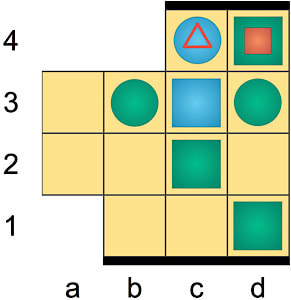

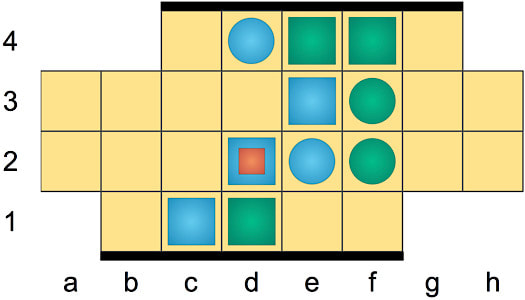

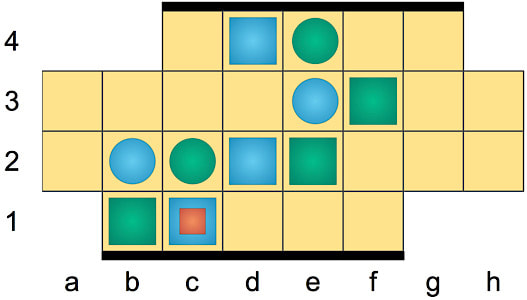

In Diagrams 3a and 3b, the marked blue circle cannot move, and a loss in the following turn is inevitable. In Diagram 3c, the blue circle can move, but none of the three available squares are safe. Note that circles can be trapped in both strong and weak corners, as well as along both the left and right edges.

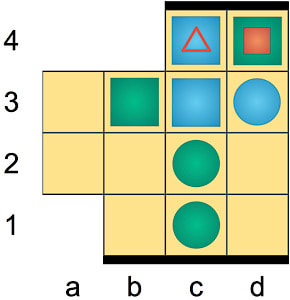

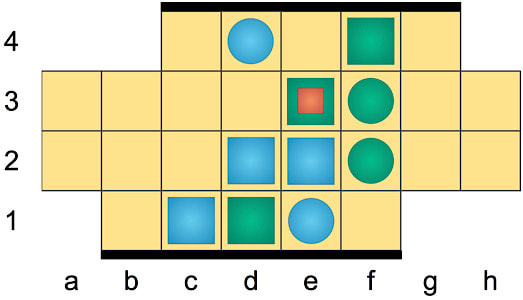

Squares are more resilient, but they can also be trapped under certain conditions. In particular, squares are susceptible in the weak corners, c4 and f1. This is demonstrated below:

Squares are more resilient, but they can also be trapped under certain conditions. In particular, squares are susceptible in the weak corners, c4 and f1. This is demonstrated below:

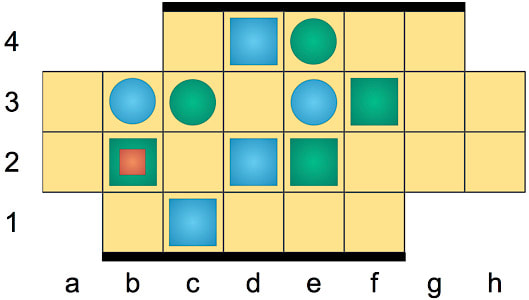

In all three diagrams, the marked blue square is doomed to be pushed off in the following turn. The siderail is instrumental in this setup; without it, Blue would be able to simply push downwards to get out of danger. This explains why squares can only be trapped in the weak corners.

Here are a few sample puzzles, demonstrating various kinds of game-ending traps. The solutions can be found here. All puzzles are Blue to move and win in two.

Here are a few sample puzzles, demonstrating various kinds of game-ending traps. The solutions can be found here. All puzzles are Blue to move and win in two.

Since there are normally an enormous number of possible moves per turn, it is rarely feasible to calculate more than a move or two in advance outside of correspondence play. With that in mind, we will discuss now the essential strategic principles of Push Fight.

Strategy

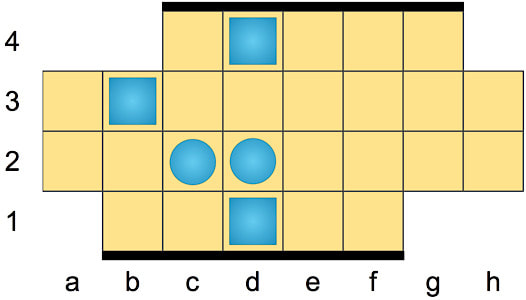

We start with the game’s opening. Openings in Push Fight are characterized by the battle for territory. As its name suggests, a player’s territory describes the set of board spaces which are inaccessible to any of her opponent’s pieces. Expanding one’s territory grants greater piece manoeuverability and piece safety.

Since Blue has the first move, Blue also has somewhat more flexibility in the opening configuration. Green has somewhat less flexibility but does have the advantage of being able to respond to Blue's setup. Green should always place four of their five pieces along the E column in order to cede as little territory to Blue as possible.

Strategy

We start with the game’s opening. Openings in Push Fight are characterized by the battle for territory. As its name suggests, a player’s territory describes the set of board spaces which are inaccessible to any of her opponent’s pieces. Expanding one’s territory grants greater piece manoeuverability and piece safety.

Since Blue has the first move, Blue also has somewhat more flexibility in the opening configuration. Green has somewhat less flexibility but does have the advantage of being able to respond to Blue's setup. Green should always place four of their five pieces along the E column in order to cede as little territory to Blue as possible.

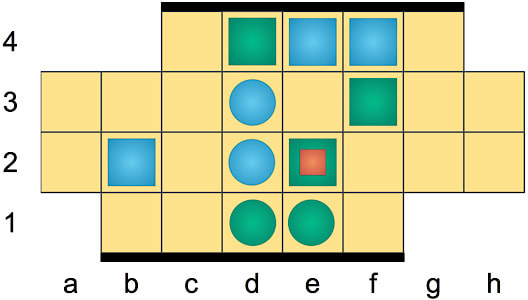

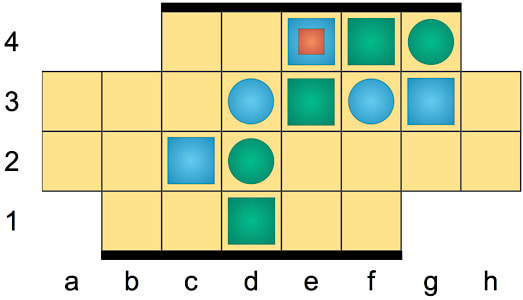

The progression above shows the typical first stages of a game. Blue's setup here is among the most flexible available (and is my personal favourite!) The usual first move, as above, is 1. c2-c3, d4-d3, b3xc3. This creates a “T”-formation out of Blue's pieces. It may seem like this move is giving up territory along the fourth row, but due to the placement of the anchor there is no good way for Green to take advantage of this. Blue often plans to follow this play up with either e3xf3, breaking into Green's territory, or c3-b3, d2-c3, b3xc3 depending on Green's play.

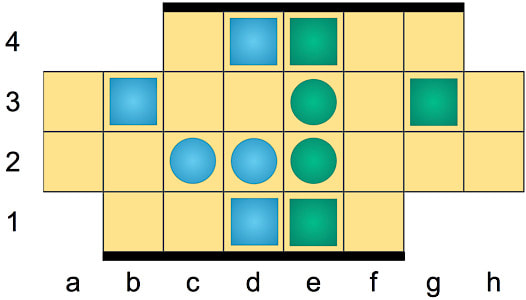

After the initial moves, the game enters its main phase. Here players try to protect their own pieces while targeting their opponent’s. Since circles cannot push, they become very vulnerable when they are separated from all squares of their colour, especially away from the centre of the board. The diagrams below show how this can even happen early on in a game. Here, Blue overextended herself in the opening; Green takes full advantage of this and takes a circle hostage. There is nothing Blue can do to save her e1 circle.

After the initial moves, the game enters its main phase. Here players try to protect their own pieces while targeting their opponent’s. Since circles cannot push, they become very vulnerable when they are separated from all squares of their colour, especially away from the centre of the board. The diagrams below show how this can even happen early on in a game. Here, Blue overextended herself in the opening; Green takes full advantage of this and takes a circle hostage. There is nothing Blue can do to save her e1 circle.

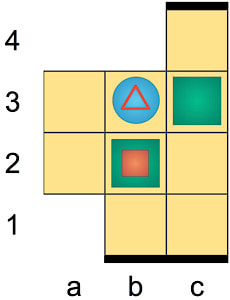

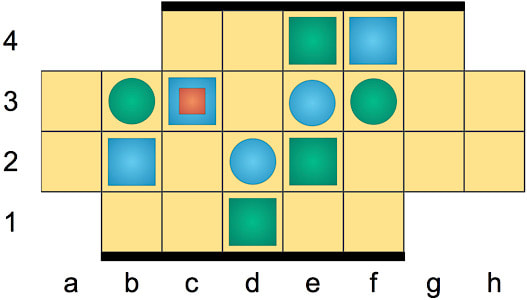

Because of the vulnerability of circles, a good rule of thumb is to try to position friendly squares between circles and the closest edge of the board. Squares in this position can make formidable defenders, as shown below. In Diagram 8a, Green cannot avoid losing her circle (and with it, the game) on the following turn. In Diagram 8b, however, Green is doing completely fine since the g4 square acts as an effective defender to the f4 circle.

Finally, we touch briefly on the subject of making threats. There is an oft-repeated quote from Chess, originally by Bobby Fischer, “Patzer sees a check, Patzer gives a check.” It describes the tendency of newer players to make threats blindly for no good reason. In Push Fight, too, it is not always a good idea to make a threat, as we will see.

The diagrams above demonstrate an extreme example of this. Blue threatens Green's square, and Green responds by forming a winning trap on Blue's circle with c2-c3, b1xb2!

The above demonstrates the “Sully Trap,” coined by Jesse Sullivan. It is often an option when one player leaves an unanchored square on either b2 or g3. After Green's move (e2-g3, d1-c2, c2xb2), Blue will need to spend her next two pushes escaping with the a2 square via a3-b3-c3 or a3-b3-b2. In the meantime, Green can make two pushes to capture Blue's f4 square and win the game.

This ends our short foray into Push Fight tactics and strategy. There’s still quite a lot yet to be discovered about the game, and I am certainly learning new things with each play. I highly recommend fans of push-based abstracts to give this one a go.

This ends our short foray into Push Fight tactics and strategy. There’s still quite a lot yet to be discovered about the game, and I am certainly learning new things with each play. I highly recommend fans of push-based abstracts to give this one a go.

David Stoner is an abstract game designer and enthusiast from the American Southeast. Push Fight is among his favourite modern abstracts, and he’s currently working to develop better bots and opening theory for the game. David is a graduate student pursuing a PhD in mathematics at Stanford University.

In my review of Push Fight in AG18, I mentioned that there were few push games, in my experience, except Push Fight and Shōbu, which we reviewed, and Abalone and Siam. That comment elicited some response, which I have reproduced below. Many thanks to these people for their feedback! Replying to Chris Huntoon's question below, yes, the Unequal Board Spaces Game Design Competition is still a possibility. I'll let you know by AG20. ~ Ed.

In my review of Push Fight in AG18, I mentioned that there were few push games, in my experience, except Push Fight and Shōbu, which we reviewed, and Abalone and Siam. That comment elicited some response, which I have reproduced below. Many thanks to these people for their feedback! Replying to Chris Huntoon's question below, yes, the Unequal Board Spaces Game Design Competition is still a possibility. I'll let you know by AG20. ~ Ed.

Just wanted to chime in on the article “Two Pushing Games: Shōbu and Push Fight” in AG18. I found two (maybe three) examples of other push games. The first one is Oshi, by Tyler Bielman and published in 2006, where the goal is to push seven points worth of the opponent’s game pieces off the board. It twists the formula a little bit by introducing differentiated pieces (three types that have a diferent number of spaces they can move, the maximum number of pieces they can push and the number of points they are worth if pushed off the board. If we consider non-combinatorial games in the mix, there is also Epigo, by Chris Gosselin and Chris Kreuter, published in 2011, where the goal is to push three of the opponents' eight pieces off the edge of the board (where the game is for 2 to 4 players). Epigo has a simultaneous action selection phase and movement programming (you select which three of your pieces and how they will move in each round) as mechanisms. I think it is also worth mentioning Arimaa, by Aamir and Omar Syed (2002), where pieces can push (and also pull) weaker pieces to the four trap squares. Although elimination is not the primary goal, which is reaching the opposite side with one of your Rabbits; elimination is a secondary goal, by eliminating all of your opponent’s Rabbits, thus making it impossible for the opponent to win. I also wanted to say thank you for reviving the magazine, it’s been a joy reading articles focused on abstract games. ~ Pablo Schulman

First off, let me say it is good to see you publishing. I appreciate the diverse range of games, as well as the detailed analysis.

Second, in AG18, in your article on push games, you asked readers to name other push games. Well one of my web-published games, Aries, is a push game. Though when I first conceived it, I didn’t think of it as a “push” game, but rather as a “ramming” game. Which is why the pieces are called “Rams.” Besides eliminating opponent’s pieces by knocking them off the edge of the board, a player can also capture enemy pieces by shoving them into a friendly piece.

Third, any plans on carrying through with that “Unequal Board Spaces Game Design” competition you mentioned in AG17?

Because I have another web-published game, Andalusia, which would fit that perfectly.

Both push games and games with unequal board spaces are very rare types of games, with only a handful of each in existence. It is nice that you are giving them some attention. ~ Chris Huntoon

Concerning push games, there's Kuba variously known by other names including Traboulet. You can play on boardspace.net. Another game which looks similar is Push on BoardGameGeek, but I haven’t yet acquired a copy. ~ Dave Dyer