Interview

Kate Jones is the founder and owner of Kadon Enterprises, which has been producing gorgeous games and puzzles for decades. Many of the images throughout this interview illustrate the geometrical puzzles created by Kate and her associates. However, Kadon also offers a selection of traditional and modern abstract games in beautiful editions. In particular, the Game of Y and *Star, both created by the legendary Ea Ea (Craige Schensted), are sold in high-quality wooden editions—I don't think Ea Ea's creations are available anywhere else. Another interesting game produced exclusively by Kadon is Quantum, which has a brilliant and unusual way of randomizing the initial position. I hope we can take a close look at Quantum in a future issue. John McCallion's questions below are italicized. ~ Ed.

Dare I say that your website is the most seductively dazzling in the world of games and puzzles? Have you been interested in this world from an early age, and what prompted your first step on a remarkable journey that began over 40 years ago?

Well, thank you for the compliment on the website that I have been building almost singlehandedly since 1998. My graphic art background and predilection for structure helped.

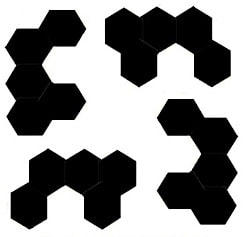

As for my interest and first steps in this direction, my short answer is Spock-like: “It was the logical thing to do.” A somewhat extended string of causality found me playing with mosaic wood tiles while bedridden with chicken pox at age 4. I would sit there and make new designs for hours. That’s probably what planted the seed of system, order, variety, combinations and permutations, symmetry and creativity, and stirred certain brain functions to life. Of course, I had no knowledge of any of those words or their meanings until decades later. I was just having fun. Decades later, this little puzzle, Rombix Jr., top left, the closest relative to my childhood set, became one of our products. As Spock would say, “Fascinating.”

As all this happened in “the old country” in a previous century, my family played classical games like Parcheesi, Rummy, Nine Men’s Morris (Muhle), and Chess, and outdoors hopscotch on the sidewalk or bouncing a tennis ball against the outside house wall, batting it with my palm sequentially from one to twenty times. All still were played with patterns and rhythms.

Geometry had captured my imagination, and later, in all my years of schooling in Germany and Connecticut, my best subjects were math and art and geometry. So were languages, since grammar and vocabulary I saw as a kind of assembly of puzzle parts into coherent structures. I loved “diagramming” sentences, a method I learned in seventh grade. And my mind made the connection to logic, order, coherence, epistemology, and truth. Of course, I knew nothing of those concepts at the time, either, though I was joyfully swimming in them with every breath.

Upon graduation from high school I worked as a Girl Friday in the advertising office of a department store in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where I learned on the job about layout (structure), copywriting (language use), and illustration (art). On the side I was offering proofreading, editing, and document preparation for individual clients. And evenings I learned to become a ballroom dance teacher, which expanded my system and structure into 3D geometry of movement and the 4th dimension of time with the rhythm of music. All fed my future path.

Fast forward past marriage, children, and divorce, I had a variety of jobs in offices dealing with documents, with private clients who needed editing and proofreading, and an evening job of teaching at a dance studio in Washington, DC. There I met the love of my life, married him, won many trophies in dance competitions, quit my day job and started my own graphic arts business in Virginia. In 1975 we moved to Iran when his engineering job sent him abroad to “transfer technology” to the Shah. As an expatriate wife, I occupied myself with helping out in a local printshop and running some dance classes for the American community. Fate took a hand.

While on a weekend jaunt to Dubai in 1976, in the airport newsstand, I came across and purchased a new book by one of my favourite sci-fi authors, Arthur C. Clarke: Imperial Earth. Fate swatted me alongside the head, because in that book Clarke described a puzzle set of 12 pieces, each a different arrangement of 5 squares. Later I learned that their name was "pentominoes.” A galactic plot hinged on forming them into a 3x20 rectangle. That task was irresistible to me, so I set the book aside and made myself some cardboard cutouts of the pieces and proceeded to try to solve them. By the time I succeeded, I was thoroughly hooked, and as the months went by, my research with them filled notebooks. Now it so happened that Iran, and particularly the city of Shiraz where we lived, has some incredible craftspeople skilled in the art of inlay. On a visit to the bazaar, filled with the aroma of a hundred spices, I searched out a craftsman and commissioned him to make me a formal set of the 12 shapes. It took a while and cost a bunch, but is probably my most beautiful possession.

Well, thank you for the compliment on the website that I have been building almost singlehandedly since 1998. My graphic art background and predilection for structure helped.

As for my interest and first steps in this direction, my short answer is Spock-like: “It was the logical thing to do.” A somewhat extended string of causality found me playing with mosaic wood tiles while bedridden with chicken pox at age 4. I would sit there and make new designs for hours. That’s probably what planted the seed of system, order, variety, combinations and permutations, symmetry and creativity, and stirred certain brain functions to life. Of course, I had no knowledge of any of those words or their meanings until decades later. I was just having fun. Decades later, this little puzzle, Rombix Jr., top left, the closest relative to my childhood set, became one of our products. As Spock would say, “Fascinating.”

As all this happened in “the old country” in a previous century, my family played classical games like Parcheesi, Rummy, Nine Men’s Morris (Muhle), and Chess, and outdoors hopscotch on the sidewalk or bouncing a tennis ball against the outside house wall, batting it with my palm sequentially from one to twenty times. All still were played with patterns and rhythms.

Geometry had captured my imagination, and later, in all my years of schooling in Germany and Connecticut, my best subjects were math and art and geometry. So were languages, since grammar and vocabulary I saw as a kind of assembly of puzzle parts into coherent structures. I loved “diagramming” sentences, a method I learned in seventh grade. And my mind made the connection to logic, order, coherence, epistemology, and truth. Of course, I knew nothing of those concepts at the time, either, though I was joyfully swimming in them with every breath.

Upon graduation from high school I worked as a Girl Friday in the advertising office of a department store in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where I learned on the job about layout (structure), copywriting (language use), and illustration (art). On the side I was offering proofreading, editing, and document preparation for individual clients. And evenings I learned to become a ballroom dance teacher, which expanded my system and structure into 3D geometry of movement and the 4th dimension of time with the rhythm of music. All fed my future path.

Fast forward past marriage, children, and divorce, I had a variety of jobs in offices dealing with documents, with private clients who needed editing and proofreading, and an evening job of teaching at a dance studio in Washington, DC. There I met the love of my life, married him, won many trophies in dance competitions, quit my day job and started my own graphic arts business in Virginia. In 1975 we moved to Iran when his engineering job sent him abroad to “transfer technology” to the Shah. As an expatriate wife, I occupied myself with helping out in a local printshop and running some dance classes for the American community. Fate took a hand.

While on a weekend jaunt to Dubai in 1976, in the airport newsstand, I came across and purchased a new book by one of my favourite sci-fi authors, Arthur C. Clarke: Imperial Earth. Fate swatted me alongside the head, because in that book Clarke described a puzzle set of 12 pieces, each a different arrangement of 5 squares. Later I learned that their name was "pentominoes.” A galactic plot hinged on forming them into a 3x20 rectangle. That task was irresistible to me, so I set the book aside and made myself some cardboard cutouts of the pieces and proceeded to try to solve them. By the time I succeeded, I was thoroughly hooked, and as the months went by, my research with them filled notebooks. Now it so happened that Iran, and particularly the city of Shiraz where we lived, has some incredible craftspeople skilled in the art of inlay. On a visit to the bazaar, filled with the aroma of a hundred spices, I searched out a craftsman and commissioned him to make me a formal set of the 12 shapes. It took a while and cost a bunch, but is probably my most beautiful possession.

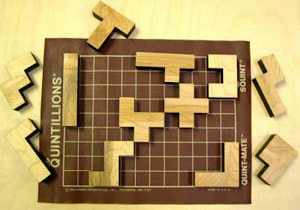

In 1978 a revolution broke out in Iran, and the Americans shipped out on 3 days’ notice. Back in Maryland, after I sold my business in Virginia, the question became: “What do I do next?” A friend suggested starting a business making that puzzle set. We explored making it in wood, found a lasershop to cut them, named them Quintillions, and the rest is history.

Selling was a whole new adventure, and I quickly learned that stores would not want to sell an item no one knew about or would require the store clerk to explain it. Moreover, a store wanted to buy it so cheap that we’d lose money on every set. So that was a no-go. Finally I found a way to market it that has worked for 40 years: sell our beautiful, unique handcrafted work at art shows, little by little adding interesting new products to our repertoire, inspired by what was becoming our leitmotif: puzzle sets of geometric shapes that represented all the members of a certain concept. Gamepuzzles was born.

Year by year I printed a bigger catalogue and pioneered both wooden and laser-cut acrylic methods of production. In 1998 came the breakthrough to computer use and a fledgling website that eventually relieved us of the expense of a printed catalogue. We owe an enormous debt to the inventors and developers of digital technology and coding. It’s like magic… type a few symbols and see a colourful presentation on-screen. Then, for good measure, print those images onto paper. Today’s generation can take all that for granted as part of normal life, with no clue of the hardships those earlier forms of documentation entailed, back to Mr. Gutenberg.

My late wife, Robin, was the puzzles expert in our household, and she was a great teacher who introduced them to me. I found them so fascinating for all levels of solver that I regret they are not more widely available. Have you ever considered letting others develop them for a mass market, or are they irrevocably destined to remain expensive artistry for connoisseurs? I would add that they are still tremendous value for your prices.

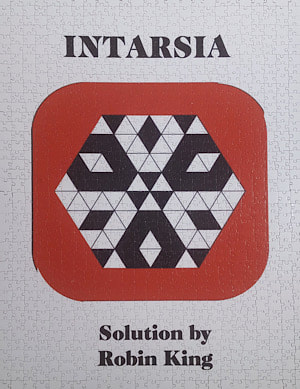

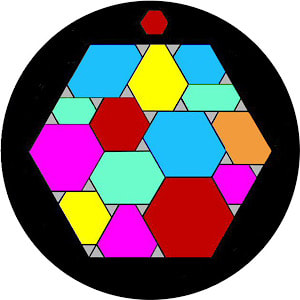

It was very gratifying to have an intellect like Robin embrace our work. I miss her, and to this day her incredible solution of our Intarsia set graces a poster, and the image below shows it made into a jig-saw puzzle.

Selling was a whole new adventure, and I quickly learned that stores would not want to sell an item no one knew about or would require the store clerk to explain it. Moreover, a store wanted to buy it so cheap that we’d lose money on every set. So that was a no-go. Finally I found a way to market it that has worked for 40 years: sell our beautiful, unique handcrafted work at art shows, little by little adding interesting new products to our repertoire, inspired by what was becoming our leitmotif: puzzle sets of geometric shapes that represented all the members of a certain concept. Gamepuzzles was born.

Year by year I printed a bigger catalogue and pioneered both wooden and laser-cut acrylic methods of production. In 1998 came the breakthrough to computer use and a fledgling website that eventually relieved us of the expense of a printed catalogue. We owe an enormous debt to the inventors and developers of digital technology and coding. It’s like magic… type a few symbols and see a colourful presentation on-screen. Then, for good measure, print those images onto paper. Today’s generation can take all that for granted as part of normal life, with no clue of the hardships those earlier forms of documentation entailed, back to Mr. Gutenberg.

My late wife, Robin, was the puzzles expert in our household, and she was a great teacher who introduced them to me. I found them so fascinating for all levels of solver that I regret they are not more widely available. Have you ever considered letting others develop them for a mass market, or are they irrevocably destined to remain expensive artistry for connoisseurs? I would add that they are still tremendous value for your prices.

It was very gratifying to have an intellect like Robin embrace our work. I miss her, and to this day her incredible solution of our Intarsia set graces a poster, and the image below shows it made into a jig-saw puzzle.

What we learned through all the years is that quality counts. It doesn’t need to be expensive, though not as cheap as plastic produced in China. We also learned that such intellectually aimed products are what you’d call a “niche” market. The mass market does not have an appreciation or even an interest in such goods, compared to what else is available out there. Also, the popular game forms (Euro games, role-playing games, LARP) and finally electronic games took over as the main interest. Tetris was a great breakthrough in popularizing puzzles of the kind we make, combining the puzzle shapes with electronic manipulation. Tetris turned millions of people into robots operating buttons that moved pieces around—not the same as our self-directed, hands-on constructions.

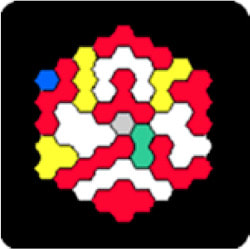

As it turned out, one enlightened game company, CEACO, and its subsidiary, Brainwright, did take the daring step of licensing three of our puzzles for mass production: Roundominoes, Hexnut Jr., and Iamond Hex.

As it turned out, one enlightened game company, CEACO, and its subsidiary, Brainwright, did take the daring step of licensing three of our puzzles for mass production: Roundominoes, Hexnut Jr., and Iamond Hex.

These three were produced in very nice laser-cut plastic in China and sold through bookstores, mainly Barnes & Noble. As the original production run sold off, however, they did not make more, and only a few are still left out there. Stores thrive on novelty and mercilessly purge old stuff, unless it reaches the stature of a standard like Chess, Checkers, Backgammon, Monopoly, or Scrabble. We would consider licensing some of our other original products, if the mass production still respected the quality and aesthetics that are our trademark. Since we never discontinue a product once we publish it, having a temporary version circulating in the commercial world and trickling some royalties our way would be fine.

And yes, our prices are very low, just about at break-even levels. We manage because of lower overhead, working on our own premises, and having a website that spares us from printing costs. And the president of the company works without pay. We give her shares of stock now and then. Most of the other long-time helpers are also shareholders. No, they don’t expect non-existing dividends.

You once stunned me by despising Checkers as a game whose object was “genocide”. Can you not convince yourself, for example, that captured pieces withdraw from society to become very successful hunter-gatherers as predicted by the Libertarian philosophy you candidly support? What is your ideal for a game, and which of those you sell best reflects this?

Wow, that’s a powerful question. Let’s look at early games that humans played. Humans are unique in creating replicas of world situations, either for amusement or for teaching. Humans are also unique in “seeing” equivalent patterns and formulating them as metaphors, similes, analogies, fables, and microcosms that deal with the survival problems in the real world. Our brains work that way. We make comparisons and categorize, replaying the world as we see it.

One of the earliest games we know of is Mancala, probably played with pebbles or kernels or even coins. I can see the caravans that brought goods across the continents, from China across Asia and the Indian subcontinent into Africa and Europe, with elephants and camels. And at night, at camp fires, the merchants would hollow out rows of bowls in the sand and play a calculating game of acquisition. Mancala is one of the oldest formatted games. Our Game of the Labyrinth, researched by Peter Aleff, may be the most ancient game board, from 3500 years ago. It is a race to the finish, not war, and allows a measure of strategic choice, not just pure luck. It is the ancestor of chance games people still play today the world over, such as Candyland, Chutes and Ladders, Parcheesi, and Sorry, that are a race to the finish on spaces the pawns follow.

Chess was born in India around the seventh century, symbolizing two armies at war, each headed by a King and Queen, with the goal of capturing/conquering the opposing king. It’s nice to think that perhaps the game was invented to substitute for actual war, and instead of slaughtering all the combatants, the losing side would simply surrender and save all the bloodshed. We see thereby that violent conquest is a fact of life among the world’s competing populations.

Checkers came from AlQuerques, an Arabic game from the tenth century, with two opposing sets of pieces bent on eliminating all of the other side. Yes, I interpret that as symbolic genocide, a practice not unknown in the ancient world when desired territories had to be emptied of occupants to make room for the conquering tribe. No delicate substitution of plot is acceptable. If the side to be eliminated is not slaughtered outright, they may escape to some other region, or they may be simply enslaved by the conqueror. Those are historical realities. These atrocities begat human invention of weaponry, non-stop, to today’s nuclear arsenal.

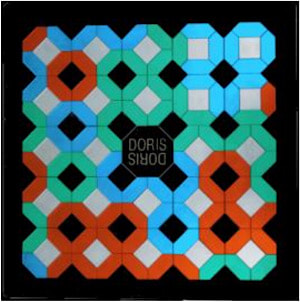

We do make one game that sugarcoats the capturing theme. In Doris, spaceships go across the void and “rescue” the other player’s spaceship by linking to it by colour and towing it back to port.

And yes, our prices are very low, just about at break-even levels. We manage because of lower overhead, working on our own premises, and having a website that spares us from printing costs. And the president of the company works without pay. We give her shares of stock now and then. Most of the other long-time helpers are also shareholders. No, they don’t expect non-existing dividends.

You once stunned me by despising Checkers as a game whose object was “genocide”. Can you not convince yourself, for example, that captured pieces withdraw from society to become very successful hunter-gatherers as predicted by the Libertarian philosophy you candidly support? What is your ideal for a game, and which of those you sell best reflects this?

Wow, that’s a powerful question. Let’s look at early games that humans played. Humans are unique in creating replicas of world situations, either for amusement or for teaching. Humans are also unique in “seeing” equivalent patterns and formulating them as metaphors, similes, analogies, fables, and microcosms that deal with the survival problems in the real world. Our brains work that way. We make comparisons and categorize, replaying the world as we see it.

One of the earliest games we know of is Mancala, probably played with pebbles or kernels or even coins. I can see the caravans that brought goods across the continents, from China across Asia and the Indian subcontinent into Africa and Europe, with elephants and camels. And at night, at camp fires, the merchants would hollow out rows of bowls in the sand and play a calculating game of acquisition. Mancala is one of the oldest formatted games. Our Game of the Labyrinth, researched by Peter Aleff, may be the most ancient game board, from 3500 years ago. It is a race to the finish, not war, and allows a measure of strategic choice, not just pure luck. It is the ancestor of chance games people still play today the world over, such as Candyland, Chutes and Ladders, Parcheesi, and Sorry, that are a race to the finish on spaces the pawns follow.

Chess was born in India around the seventh century, symbolizing two armies at war, each headed by a King and Queen, with the goal of capturing/conquering the opposing king. It’s nice to think that perhaps the game was invented to substitute for actual war, and instead of slaughtering all the combatants, the losing side would simply surrender and save all the bloodshed. We see thereby that violent conquest is a fact of life among the world’s competing populations.

Checkers came from AlQuerques, an Arabic game from the tenth century, with two opposing sets of pieces bent on eliminating all of the other side. Yes, I interpret that as symbolic genocide, a practice not unknown in the ancient world when desired territories had to be emptied of occupants to make room for the conquering tribe. No delicate substitution of plot is acceptable. If the side to be eliminated is not slaughtered outright, they may escape to some other region, or they may be simply enslaved by the conqueror. Those are historical realities. These atrocities begat human invention of weaponry, non-stop, to today’s nuclear arsenal.

We do make one game that sugarcoats the capturing theme. In Doris, spaceships go across the void and “rescue” the other player’s spaceship by linking to it by colour and towing it back to port.

You mention hunter-gatherers. That mentality, unfortunately, is still with us, taking whatever one can, disregarding the civilized development of property rights. Plunder and expropriation are official policy, called taxes. If you become too successful, you are condemned as “rich” and must be made to give it back. That is not Libertarian philosophy. So the game of Monopoly emerged, a tribute to avarice and gloating over the misfortunes of others. Notice that it throws the players into impoverishment not through their own choice but by roll of the dice. In real life, people can avoid going to spaces that impoverish.

Games of chance are a two-edged sword: they can dump the players into misfortune against their better judgment, or they can console a player that next time will be luckier. So I’m not fond of dice games in general.

We can trace social developments through the evolution of games. Conflict is usually the main draw, and overcoming a specific opponent is the usual goal. Educational strategies that apply in real-life situations are a kind of indoctrination. They intend to habituate players’ conscience to accept destruction of the opponent as pleasurable. I consider that unconscionable.

From what I understand of Dungeons & Dragons, it operates on human teams collaborating and pooling their various individual skills and powers to defeat some non-human monsters or other symbolic evils, and that is a historic innovation. Bravo, Gary Gygax.

My ideal for a game is indeed non-predatory, cooperative and mutual problem-solving, positive achievement, not viewing the other player(s) as enemies. In some of my more recent games, players can trade pieces if it helps both of them to complete a figure or goal and even earn bonus points for that. Another theme is where all players contribute to a mutual goal, and where each player’s contribution is important, and all players win. “Trade” is one of the non-predatory objectives, in the games Marshall Squares and MemorIQ.

Games of chance are a two-edged sword: they can dump the players into misfortune against their better judgment, or they can console a player that next time will be luckier. So I’m not fond of dice games in general.

We can trace social developments through the evolution of games. Conflict is usually the main draw, and overcoming a specific opponent is the usual goal. Educational strategies that apply in real-life situations are a kind of indoctrination. They intend to habituate players’ conscience to accept destruction of the opponent as pleasurable. I consider that unconscionable.

From what I understand of Dungeons & Dragons, it operates on human teams collaborating and pooling their various individual skills and powers to defeat some non-human monsters or other symbolic evils, and that is a historic innovation. Bravo, Gary Gygax.

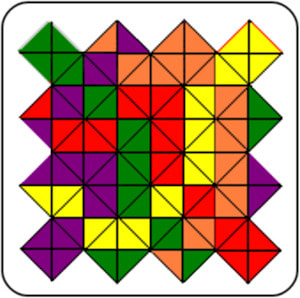

My ideal for a game is indeed non-predatory, cooperative and mutual problem-solving, positive achievement, not viewing the other player(s) as enemies. In some of my more recent games, players can trade pieces if it helps both of them to complete a figure or goal and even earn bonus points for that. Another theme is where all players contribute to a mutual goal, and where each player’s contribution is important, and all players win. “Trade” is one of the non-predatory objectives, in the games Marshall Squares and MemorIQ.

Perhaps my most unusual game is Fox Blox, a set of 4 cubes containing one complete alphabet, one letter per side plus two sides with two letters. The goal is to make sentences using four letters rolled randomly as the initials of different words. Each player rolls and adds a new line, and pairs of lines must rhyme. There are no wrong answers, and players can suggest words even when it’s not their turn. Everyone wins when the opus is complete. It’s hilarious.

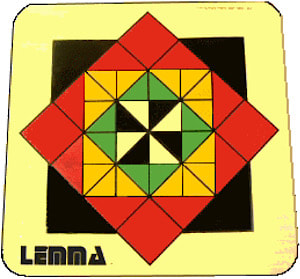

My other unique and non-predatory game is Lemma, a rule-inventing meta-game where each turn adds one new rule, along with a piece placement or movement that shows that rule in action. All rules stay in effect, and no action may go against any previous rule, and no new rule may contradict any previous rule. Wild! The board design lets players use points, lines, and spaces in every possible way their imaginations may suggest. There are even some more normal games playable on this grid, like AlQuerques and a sort of Chinese Checkers, plus hundreds of solitaire puzzles.

If you miraculously find time to explore games not produced by you, what are your favourites? Can you nominate a game you detest even more than Checkers?

Well, I have played and enjoyed several games not of our own making, like Backgammon (learned it in Iran, where it was invented), notwithstanding that it uses dice. It is a race to the finish, not a war of annihilation. Likewise, Chinese Checkers is a race, not war, and there are some very beautiful sets made in wood by craftsmen I know. I absolutely love another game I wish we had made, and that is Set. Find a matching group of cards with all the same or all different characteristics. Superb! One of our products has such a theme, but they did it much better. One other game that I don’t have time to play but wish I could is the very attractive Qwirkle that is a kissing cousin of our style of game.

As for what game I detest more than Checkers, I’m not sure there is anything more despicable than genocide. Football comes close, since it requires players to physically damage each other, notwithstanding helmets and padding, with the symbolism of getting their sperm (the ball) into the other team’s receptacle. Rape? Bet you’ve never thought of football in those terms.

Do you welcome submissions from unknown game designers? How have you found talented designers in the past?

I frequently receive appeals from designers to publish their work. I have a soft spot in my head and heart for my fellow creative spirits, so will take a thorough look at their sendings. Unfortunately, I have a very specific list of criteria, and very few submissions come close to meeting them. Nevertheless, over the years there have been several designers who have found us—I don’t go looking for them—and come up with great ideas that I’ve been able to develop and style in award-winning ways. I always tell them, though, that they ought to try with the “big” game companies first, since we are a low-circulation niche operation and will not make them rich. The one thing I can promise them is that if I publish it, I will never discontinue it. We pay decent royalties and highlight inventors in our website, so they don’t stay “unknown” for long.

Some of our best ideas have come from within our own team of helpers who get inspired by our product line to create compatible designs, like Thomas Atkinson’s Hopscotch and Elijah Allen’s Four Horses of the Epic Ellipse and MiniTouch-I. I get the fun of naming them. Elijah has a new boardgame we’ll be publishing soon of major philosophical import: the cosmic struggle between good and evil.

If you miraculously find time to explore games not produced by you, what are your favourites? Can you nominate a game you detest even more than Checkers?

Well, I have played and enjoyed several games not of our own making, like Backgammon (learned it in Iran, where it was invented), notwithstanding that it uses dice. It is a race to the finish, not a war of annihilation. Likewise, Chinese Checkers is a race, not war, and there are some very beautiful sets made in wood by craftsmen I know. I absolutely love another game I wish we had made, and that is Set. Find a matching group of cards with all the same or all different characteristics. Superb! One of our products has such a theme, but they did it much better. One other game that I don’t have time to play but wish I could is the very attractive Qwirkle that is a kissing cousin of our style of game.

As for what game I detest more than Checkers, I’m not sure there is anything more despicable than genocide. Football comes close, since it requires players to physically damage each other, notwithstanding helmets and padding, with the symbolism of getting their sperm (the ball) into the other team’s receptacle. Rape? Bet you’ve never thought of football in those terms.

Do you welcome submissions from unknown game designers? How have you found talented designers in the past?

I frequently receive appeals from designers to publish their work. I have a soft spot in my head and heart for my fellow creative spirits, so will take a thorough look at their sendings. Unfortunately, I have a very specific list of criteria, and very few submissions come close to meeting them. Nevertheless, over the years there have been several designers who have found us—I don’t go looking for them—and come up with great ideas that I’ve been able to develop and style in award-winning ways. I always tell them, though, that they ought to try with the “big” game companies first, since we are a low-circulation niche operation and will not make them rich. The one thing I can promise them is that if I publish it, I will never discontinue it. We pay decent royalties and highlight inventors in our website, so they don’t stay “unknown” for long.

Some of our best ideas have come from within our own team of helpers who get inspired by our product line to create compatible designs, like Thomas Atkinson’s Hopscotch and Elijah Allen’s Four Horses of the Epic Ellipse and MiniTouch-I. I get the fun of naming them. Elijah has a new boardgame we’ll be publishing soon of major philosophical import: the cosmic struggle between good and evil.

Our international stable of talents is quite impressive, and many of our products have quite a pedigree. Our youngest was a high school student! We have inventors from Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, France, Brazil, Serbia, England, Switzerland, Thailand, Canada, U.S., Australia, New Zealand… amazing, isn’t it? Sadly, after 40 years a few have passed away; their names continue in the website with an eternal flame.

The one unique aspect of our enterprise is that we don’t borrow. Everything is financed from within, so a new product has to wait until there is enough saved up to launch it and cover the costs of its production and introduction. So there are always new ideas simmering on a backburner and, right now (2020), two hot items are bubbling over in front.

We introduced four terrific new ones by outside designers in 2019: Hex-Pave by Carl Hoff, Shardinaires-9 by George Sicherman, StarHex-I by Theo Geerinck, and Twenty-Tans by Hans Weidig IV.

The one unique aspect of our enterprise is that we don’t borrow. Everything is financed from within, so a new product has to wait until there is enough saved up to launch it and cover the costs of its production and introduction. So there are always new ideas simmering on a backburner and, right now (2020), two hot items are bubbling over in front.

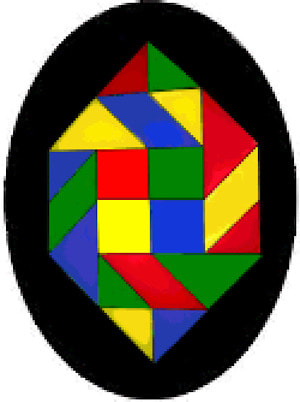

We introduced four terrific new ones by outside designers in 2019: Hex-Pave by Carl Hoff, Shardinaires-9 by George Sicherman, StarHex-I by Theo Geerinck, and Twenty-Tans by Hans Weidig IV.

Hans Weidig has become a member of Kadon’s inner circle of shareholders, helpers, and designers. He is one of the gamemasters at our Maryland Renaissance Festival pavilion, and his Twenty-Tans is a clever take-off on tangrams with four colours and wicked challenges. His new boardgame design is in R&D.

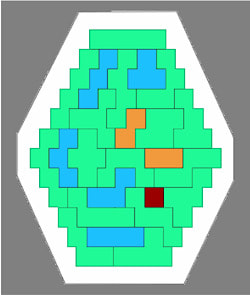

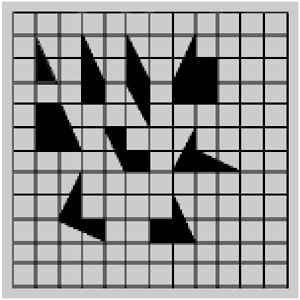

I must mention that the Shardinaires-9 set is especially significant because it represents an amazing dissection of a square into nine all-different tiles that can be arranged to form any of the 12 pentominoes (remember those—our first puzzle?) and any of the five tetrominoes (the shapes that Tetris made famous). That means that five squares can be equal in area to four squares. Whee! See the shapes of the tiles with their hypotenuse cutting through the diagonal of… not a square but a domino! This design of George Sicherman’s is so brilliant that he wins our Gamepuzzles Annual Pentomino Excellence award for 2019. Continuing research with the set is turning up ever new discoveries of symmetries, convex and concave polygons, and fanciful figures, like this little running man below. The strategy game I invented for it is another non-violent new theme: build a polygon by adding one piece at a time and score the number of perimeter edges you form; then reposition any one piece and score the number by which the perimeter length has been reduced.

Play on!

I must mention that the Shardinaires-9 set is especially significant because it represents an amazing dissection of a square into nine all-different tiles that can be arranged to form any of the 12 pentominoes (remember those—our first puzzle?) and any of the five tetrominoes (the shapes that Tetris made famous). That means that five squares can be equal in area to four squares. Whee! See the shapes of the tiles with their hypotenuse cutting through the diagonal of… not a square but a domino! This design of George Sicherman’s is so brilliant that he wins our Gamepuzzles Annual Pentomino Excellence award for 2019. Continuing research with the set is turning up ever new discoveries of symmetries, convex and concave polygons, and fanciful figures, like this little running man below. The strategy game I invented for it is another non-violent new theme: build a polygon by adding one piece at a time and score the number of perimeter edges you form; then reposition any one piece and score the number by which the perimeter length has been reduced.

Play on!

© 2020 Kadon Enterprises,Inc. All product names shown are proprietary trademarks of their respective manufacturers.

We were very pleased for John McCallion to conduct this interview with Kate Jones. John withdrew entirely from the world of games after the passing of his wife, Robin King, in 2013. Only his long and close connection with Kate could entice him to return briefly from retirement for this interview. The story of John and Robin is explained in a BoardGameGeek post. It was a relationship that began with correspondence Chess and continued with their love of games more generally. I have known John since my days with the correspondence games club, kNights of the Square Table (NOST) in the late 1990's, even before the initial run of Abstract Games. (See also the Super Chess article in this issue.) John was then editor of the NOST journal Nost-algia, and subsequently Traditional Boardgames Editor for Games magazine. He and Robin were close associates in New York of iconic game designer, author, and collector Sid Sackson. ~ Ed.