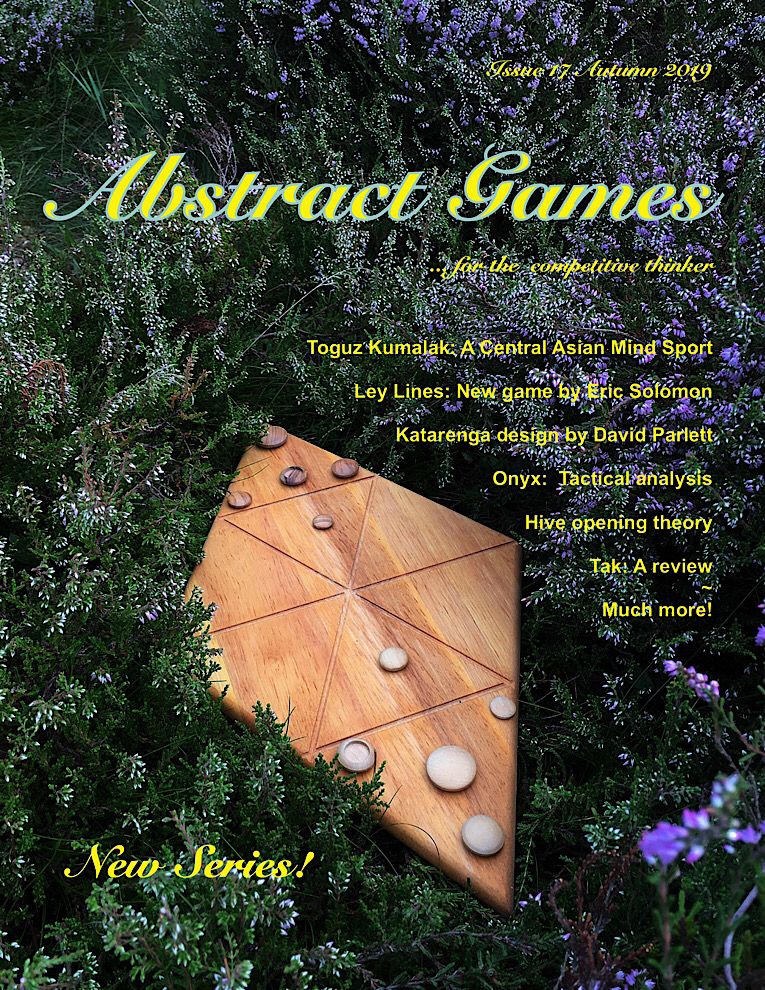

Issue 17 - Autumn 2019

Zhadu was designed by Rodney Frederickson in 1995 and was first made available around 2000-2001. Rodney's second actually published game is Qyshinsu, although he has designed several other games. We reviewed Zhadu briefly in AG11, and we will cover his new game, Karvilaj, in the next issue.

Zhadu is a small game, as each player has only five pieces, the 1-stone, 2-stone, 3-stone, 4-stone, and 1-2-3-stone. Pieces may occupy the corners or the centres of triangles on the board, and must move a number of spaces equal to their name designations. Capture is by replacement, as in Chess. A key feature of Zhadu, the source of its strategy and enduring interest, is its objective: you win when the first and last of the pieces you capture total four. Achieving the winning condition is called, remembering the Sharing. For example, an initial capture of the 4-stone is an immediate win, because it is simultaneously the first and last piece captured. On the other hand, capture of the 4-stone after capturing any other piece is not a win. The 1-2-3-stone is particularly important because it can combine with three other pieces for a win.

The second interesting feature of Zhadu is that the game is situated within a particular world, which is hinted at in the literature originally distributed by its designer—see Zhadu: The legend of the sharing. In this world, the play of the game has metaphorical significance. Zhadu is a game that I keep returning to over the years, and one of the charms of Zhadu is that it is so well suited to be the special game of an ancient culture. Even the effort needed to see move options in this game somehow seems appropriate: "Clarity comes with practice."

The use of a game as an anchor for world-building is interesting, and perhaps a reversal of the usual order. Jetan, for example, is a game of Mars, from the Martian series of Edgar Rice Burroughs, as covered in AG6, AG7, AG8, and AG14. Tak, reviewed in this issue, began as a fictional game in Patrick Rothfuss's fantasy world. Star Trek 3D Chess, discussed in AG13, is a science fiction icon.

Zhadu and Tak have no theme, and Jetan and Star Trek 3D Chess have wargame themes only to the extent that Chess also is a wargame. However, all four games are situated in particular fictional contexts—virtual themes. The games remain abstract, but they are games that belong to fictional worlds. The virtual theme of a game is irrelevant to the game itself, even as it may contribute to a game's charm. ~ Ed.

Zhadu is a small game, as each player has only five pieces, the 1-stone, 2-stone, 3-stone, 4-stone, and 1-2-3-stone. Pieces may occupy the corners or the centres of triangles on the board, and must move a number of spaces equal to their name designations. Capture is by replacement, as in Chess. A key feature of Zhadu, the source of its strategy and enduring interest, is its objective: you win when the first and last of the pieces you capture total four. Achieving the winning condition is called, remembering the Sharing. For example, an initial capture of the 4-stone is an immediate win, because it is simultaneously the first and last piece captured. On the other hand, capture of the 4-stone after capturing any other piece is not a win. The 1-2-3-stone is particularly important because it can combine with three other pieces for a win.

The second interesting feature of Zhadu is that the game is situated within a particular world, which is hinted at in the literature originally distributed by its designer—see Zhadu: The legend of the sharing. In this world, the play of the game has metaphorical significance. Zhadu is a game that I keep returning to over the years, and one of the charms of Zhadu is that it is so well suited to be the special game of an ancient culture. Even the effort needed to see move options in this game somehow seems appropriate: "Clarity comes with practice."

The use of a game as an anchor for world-building is interesting, and perhaps a reversal of the usual order. Jetan, for example, is a game of Mars, from the Martian series of Edgar Rice Burroughs, as covered in AG6, AG7, AG8, and AG14. Tak, reviewed in this issue, began as a fictional game in Patrick Rothfuss's fantasy world. Star Trek 3D Chess, discussed in AG13, is a science fiction icon.

Zhadu and Tak have no theme, and Jetan and Star Trek 3D Chess have wargame themes only to the extent that Chess also is a wargame. However, all four games are situated in particular fictional contexts—virtual themes. The games remain abstract, but they are games that belong to fictional worlds. The virtual theme of a game is irrelevant to the game itself, even as it may contribute to a game's charm. ~ Ed.