Game development

The origin of the game

In October 2019 at the Essen Game Fair, HUCH! at last launched my game Fenix after three years of negotiation and testing. Three years seems to be a long time. However, at the same time as they took an option on Fenix in 2017, HUCH! licensed Kris Burm's GIPF series. The latter was prioritized, delaying the publication of Fenix. But for me the wait was really not that long. Fenix originated four decades ago when I was still young and at the dawn of my game-design career. I am really proud that this game at last reached the market in such a wonderful design.

The story of how this game was developed and why I think it is my best strategic abstract game will be explained in telling you its history. The game Fenix has existed, although under a different name, for over 45 years. I had it registered and copyrighted in July 1975 in the (now defunct) SEBA Foundation under the name Strike.

In 1974 my day job was in administration of accommodation at the University of Amsterdam. Over lunch, my colleagues used to play games. They played Chess or International Checkers, but the Chess players did not like to play Checkers, and vice versa the Checkers players did not want to play Chess. To cool tempers down, when at a certain moment they wanted to split up and go their separate ways, I said, "There is no need to quarrel! I will invent another game as interesting as both of these so we can all keep on playing together.”

At that time, I had been thinking for a year about a game-mechanism for an abstract game in which captured higher-valued pieces could be reconstituted out of other pieces on the board. Of course, this was a nice idea, but to get from idea to reality within the boundaries of a game proved to be not so easy. What should be the size of the board? How many game pieces were needed? How could I make the game interesting and with an internal consistency? And above all, the game should be playable in the duration of lunchtime!

After much trial and error and a lot of playtesting with my game-loving friends the 9x9 squared board and 28 playing discs per player proved to be the best option for an interesting game.

I provided a few game sets for my colleagues. The boards were drawn on cardboard. For the pieces, I was lucky to find in the Waterlooplein (a famous flea-market in Amsterdam) some cheap boxes of damstenen (checkers). After I explained the rules and donated the sets, everybody adopted Strike enthusiastically, and from that moment on Strike was the only game played at the office during lunchtime. For some 20 years thereafter the game was stored in my files. I took out the prototype once in a while when interested players asked to play Strike on our game nights.

I could not have been more surprised when some 25 years later, in early 2000, I stumbled upon a former colleague from the Univesity of Amsterdam. After we exchanged greetings, he jabbed a finger at my chest and said, “Do you remember that game of yours, Strike? We’re still playing it!” I was flabbergasted that the game was still being played in that same office after all this time. It certainly says something about the longevity and durability of the game!

Earlier, in the 1990's I was introduced to the famous game inventor Alex Randolph at a Board Games Studies (BGS) Colloquium. I had brought the game Strike along with me and showed it to Alex. He was interested in Strike and above all in the principle of reconstituting higher-valued pieces—which he thought was a real innovation. We exchanged addresses, and I sent him a prototype copy of Strike. In a return letter Alex suggested a different name. In his opinion, the game deserved a “better” name and his suggestion was Phoenix, after the mythological bird which rises again from its own ashes.

Then, when HUCH! expressed interest in Strike, because of their plans to publish a series of abstract games, I immediately proposed Alex’s suggestion, Phoenix, instead of the original name, as a way of honouring Alex. HUCH! agreed with the name-change, although they thought it was better written in a more “international” way: Fenix.

In addition, although HUCH!'s test panel found the game very interesting, they thought it was in some ways too complicated. They asked me to develop a “junior” or “simpler” version, which players could start with to learn the rules and some tactics before graduating to the “regular” game. They reduced the board to 8 x 7 squares and the number of pieces for a player to 21, for a less complicated and faster game. In tests the gameplay was definitely easier, but at the same time players had to use slightly different tactics. Both versions are included in the box of the published game.

Before HUCH! took an option on the game it was used in 2005 as a Christmas gift for the members of a volunteer organization, where I was the Chairman of the Board. One hundred cardboard game boxes with wooden game materials inside were manufactured by Gerhards Spiel & Design in their usual wonderful execution. Three of my games were playable with each of these sets, Strike, Fianco, and Renpaarden. The director of the firm, my friend Ludwig Gerhards, gave me a more luxurious game set with steel pieces as a “Thank you!” for the order. (See the image below.)

In October 2019 at the Essen Game Fair, HUCH! at last launched my game Fenix after three years of negotiation and testing. Three years seems to be a long time. However, at the same time as they took an option on Fenix in 2017, HUCH! licensed Kris Burm's GIPF series. The latter was prioritized, delaying the publication of Fenix. But for me the wait was really not that long. Fenix originated four decades ago when I was still young and at the dawn of my game-design career. I am really proud that this game at last reached the market in such a wonderful design.

The story of how this game was developed and why I think it is my best strategic abstract game will be explained in telling you its history. The game Fenix has existed, although under a different name, for over 45 years. I had it registered and copyrighted in July 1975 in the (now defunct) SEBA Foundation under the name Strike.

In 1974 my day job was in administration of accommodation at the University of Amsterdam. Over lunch, my colleagues used to play games. They played Chess or International Checkers, but the Chess players did not like to play Checkers, and vice versa the Checkers players did not want to play Chess. To cool tempers down, when at a certain moment they wanted to split up and go their separate ways, I said, "There is no need to quarrel! I will invent another game as interesting as both of these so we can all keep on playing together.”

At that time, I had been thinking for a year about a game-mechanism for an abstract game in which captured higher-valued pieces could be reconstituted out of other pieces on the board. Of course, this was a nice idea, but to get from idea to reality within the boundaries of a game proved to be not so easy. What should be the size of the board? How many game pieces were needed? How could I make the game interesting and with an internal consistency? And above all, the game should be playable in the duration of lunchtime!

After much trial and error and a lot of playtesting with my game-loving friends the 9x9 squared board and 28 playing discs per player proved to be the best option for an interesting game.

I provided a few game sets for my colleagues. The boards were drawn on cardboard. For the pieces, I was lucky to find in the Waterlooplein (a famous flea-market in Amsterdam) some cheap boxes of damstenen (checkers). After I explained the rules and donated the sets, everybody adopted Strike enthusiastically, and from that moment on Strike was the only game played at the office during lunchtime. For some 20 years thereafter the game was stored in my files. I took out the prototype once in a while when interested players asked to play Strike on our game nights.

I could not have been more surprised when some 25 years later, in early 2000, I stumbled upon a former colleague from the Univesity of Amsterdam. After we exchanged greetings, he jabbed a finger at my chest and said, “Do you remember that game of yours, Strike? We’re still playing it!” I was flabbergasted that the game was still being played in that same office after all this time. It certainly says something about the longevity and durability of the game!

Earlier, in the 1990's I was introduced to the famous game inventor Alex Randolph at a Board Games Studies (BGS) Colloquium. I had brought the game Strike along with me and showed it to Alex. He was interested in Strike and above all in the principle of reconstituting higher-valued pieces—which he thought was a real innovation. We exchanged addresses, and I sent him a prototype copy of Strike. In a return letter Alex suggested a different name. In his opinion, the game deserved a “better” name and his suggestion was Phoenix, after the mythological bird which rises again from its own ashes.

Then, when HUCH! expressed interest in Strike, because of their plans to publish a series of abstract games, I immediately proposed Alex’s suggestion, Phoenix, instead of the original name, as a way of honouring Alex. HUCH! agreed with the name-change, although they thought it was better written in a more “international” way: Fenix.

In addition, although HUCH!'s test panel found the game very interesting, they thought it was in some ways too complicated. They asked me to develop a “junior” or “simpler” version, which players could start with to learn the rules and some tactics before graduating to the “regular” game. They reduced the board to 8 x 7 squares and the number of pieces for a player to 21, for a less complicated and faster game. In tests the gameplay was definitely easier, but at the same time players had to use slightly different tactics. Both versions are included in the box of the published game.

Before HUCH! took an option on the game it was used in 2005 as a Christmas gift for the members of a volunteer organization, where I was the Chairman of the Board. One hundred cardboard game boxes with wooden game materials inside were manufactured by Gerhards Spiel & Design in their usual wonderful execution. Three of my games were playable with each of these sets, Strike, Fianco, and Renpaarden. The director of the firm, my friend Ludwig Gerhards, gave me a more luxurious game set with steel pieces as a “Thank you!” for the order. (See the image below.)

In the same year of 2005, the basic principles of Strike were used in a proposal by the small company Nova Carta (a company with which I was associated) for a series of games for the television company TALPA. On a board inspired by the TALPA logo I had developed a simple version of Strike. In the end this venture was not to be, as everything was canceled by TALPA.

In any case, finally HUCH! has published Strike/Fenix, and now, 45 years after its conception the game is on the market in a really beautiful execution.

In any case, finally HUCH! has published Strike/Fenix, and now, 45 years after its conception the game is on the market in a really beautiful execution.

🔴⚫️🔴⚫️🔴⚫️🔴

Original rules

Here now are the original rules of Fenix, as recorded by my game friend David Parlett. [We have made minor edits and added diagrams. ~ Ed.]

1. Strike is played on a board of 81 squares (9x9) with 56 pieces divided into two sets of 28 pieces of different colours, conventionally red and black.

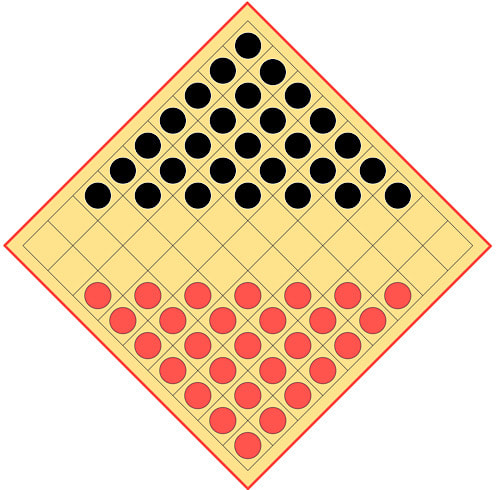

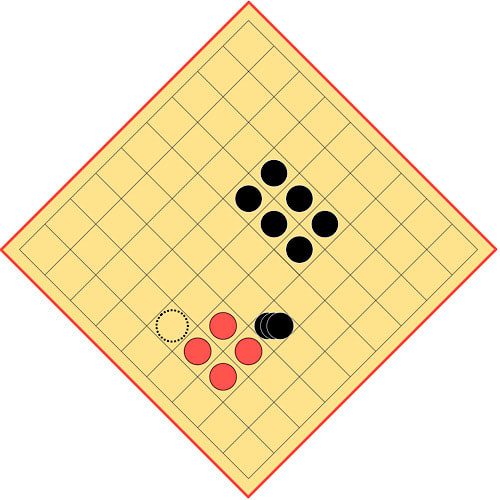

2. At the start of each game the pieces are arranged as shown in Figure 1.

Here now are the original rules of Fenix, as recorded by my game friend David Parlett. [We have made minor edits and added diagrams. ~ Ed.]

1. Strike is played on a board of 81 squares (9x9) with 56 pieces divided into two sets of 28 pieces of different colours, conventionally red and black.

2. At the start of each game the pieces are arranged as shown in Figure 1.

3. Red starts and the turn to play alternates. A piece once touched must be played.

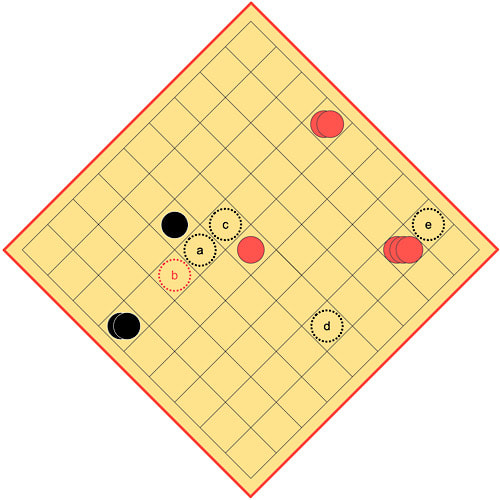

4. Each player, on their first five turns, uses some of their own pieces to create one King and three Generals [the latter alternatively called "Councillors"], in any preferred order. A General is made by placing any single piece on top of an orthogonally adjacent piece, and a King is made by placing any single piece on top of an orthogonally adjacent General. After the first five turns you will therefore possess: 1 King (a stack of three pieces); 3 Generals (stacks of two pieces each); and 19 Soldiers (singletons).

5. To continue, Red starts by moving a Soldier, a General, or his King.

4. Each player, on their first five turns, uses some of their own pieces to create one King and three Generals [the latter alternatively called "Councillors"], in any preferred order. A General is made by placing any single piece on top of an orthogonally adjacent piece, and a King is made by placing any single piece on top of an orthogonally adjacent General. After the first five turns you will therefore possess: 1 King (a stack of three pieces); 3 Generals (stacks of two pieces each); and 19 Soldiers (singletons).

5. To continue, Red starts by moving a Soldier, a General, or his King.

- Soldiers move orthogonally one step to an adjacent square.

- Generals move any distance in a straight line orthogonally, like a Chess Rook.

- The King moves one step to any adjacent square, like a Chess King.

6. Capture is compulsory if possible.

7. If more than one capture is possible you must choose that which captures the greatest number of pieces, counting a King as three, a General as two, and a Soldier as one. If two possible capturing moves offer an equal number of pieces, you may freely choose between them.

- A Soldier or King captures by jumping over an enemy piece occupying a square to which it can legally move and landing on the square immediately beyond it in the same direction, provided that the landing square is vacant.

- A General captures in the same way, but may move any number of vacant squares before the captured piece, and may land on any successive vacant square in line of travel beyond the captured piece.

7. If more than one capture is possible you must choose that which captures the greatest number of pieces, counting a King as three, a General as two, and a Soldier as one. If two possible capturing moves offer an equal number of pieces, you may freely choose between them.

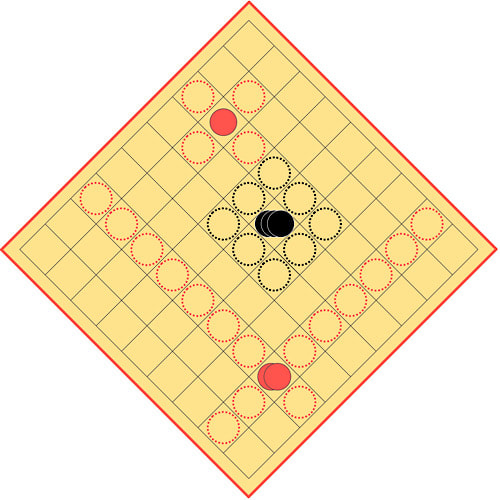

Figure 3: The black Soldier can capture a King and Soldier by jumping to a then b. The Soldier cannot continue capturing to c because it does not move diagonally. The black General has a possible capture of three Soldiers by jumping to e, f, and g; however, alternatively the black General can capture a Soldier and King by moving to h and i, say; the latter option must be taken, because it results in four pieces captured, rather than three, even though there are fewer jumps. The black King can capture a single Soldier by jumping to j; however, it can also capture King and Soldier by jumping to f and k; this latter option must be selected.

8. If one or more of your Generals is captured in one turn, you may use your next turn to create just one General (not more) from two orthogonally adjacent Soldiers anywhere on the board. However, you may not also move in the same turn. If you do move, instead of creating another General, then the right to create a General is lost.

9. If your King is captured you must, if possible, use your next turn to create another King by placing a Soldier on top of an adjacent General. This counts as a turn, and it prevents you from creating another General if one or more was taken in the same turn as the King. [To clarify, re-instantiating a General or King takes precedence over a capture; the capture would otherwise be compulsory. ~ Ed.]

10. If you are unable to create another King, when your King is captured, you lose the game.

11. You also lose if you repeat the same sequence of moves for the third time.

12. If neither player can capture the other’s King, the game is drawn.

Published rules

The published rules with the HUCH! set differ from the rules above. The word "adjacent" is missing when creation of the Generals and King at the start of the game is described. It makes for a slightly different game. In my discussion with the publisher, after receiving the printed games, we agreed that changing was no option, so I returned to my test-players and we tried it in this new way.

The judgment was unanimous that you could start the game very well this way. However, it generated a different strategy in the opening phase of the game, if Soldiers are stacked that do not have to start orthogonally adjacent to each other. In the original game it is risky to use pieces from the "frontline" to make a General or a King. Now it is easy to take a piece from the frontline and use it in a crowd of Soldiers further back to make a General or King.

In the original rules, one of the key strategic factors of the first phase is the compulsory creation of empty squares within the players' starting formations. This is what I planned when inventing the game. With the new rule it is possible to create a tight-knit army without empty squares in its midst.

Note that the new rule has even more impact when playing with the smaller board, as we found out when test-playing.

I myself prefer the original way of making the Generals and King—I have no hard proof, but I think it the game is strategically more interesting if you are forced to create "holes" in your army. Nevertheless, I have to accept that people will tend to play the game according to the published rules. Readers of this article, and anyone else who knows Strike/Fenix can make their own choice.

9. If your King is captured you must, if possible, use your next turn to create another King by placing a Soldier on top of an adjacent General. This counts as a turn, and it prevents you from creating another General if one or more was taken in the same turn as the King. [To clarify, re-instantiating a General or King takes precedence over a capture; the capture would otherwise be compulsory. ~ Ed.]

10. If you are unable to create another King, when your King is captured, you lose the game.

11. You also lose if you repeat the same sequence of moves for the third time.

12. If neither player can capture the other’s King, the game is drawn.

Published rules

The published rules with the HUCH! set differ from the rules above. The word "adjacent" is missing when creation of the Generals and King at the start of the game is described. It makes for a slightly different game. In my discussion with the publisher, after receiving the printed games, we agreed that changing was no option, so I returned to my test-players and we tried it in this new way.

The judgment was unanimous that you could start the game very well this way. However, it generated a different strategy in the opening phase of the game, if Soldiers are stacked that do not have to start orthogonally adjacent to each other. In the original game it is risky to use pieces from the "frontline" to make a General or a King. Now it is easy to take a piece from the frontline and use it in a crowd of Soldiers further back to make a General or King.

In the original rules, one of the key strategic factors of the first phase is the compulsory creation of empty squares within the players' starting formations. This is what I planned when inventing the game. With the new rule it is possible to create a tight-knit army without empty squares in its midst.

Note that the new rule has even more impact when playing with the smaller board, as we found out when test-playing.

I myself prefer the original way of making the Generals and King—I have no hard proof, but I think it the game is strategically more interesting if you are forced to create "holes" in your army. Nevertheless, I have to accept that people will tend to play the game according to the published rules. Readers of this article, and anyone else who knows Strike/Fenix can make their own choice.

🔴⚫️🔴⚫️🔴⚫️🔴

Strategy

All comments on strategy concern the game on the larger 9x9 board with the original rules. As mentioned above, the smaller board was the publisher's initiative. I tested the small version many times with other game-buffs. Our opinion was that the game’s strategy was not very different, except that attacking starts immediately and the game moves to the endgame much more quickly than on the larger board.

Although I invented Fenix, I am not a good player because, as is the case with most of my game playing, I play by intuition rather than analysis. Hopefully, nevertheless, I can tell you something of the strategic ideas in the game.

Opening

In the opening the players start to arrange their armies to provide a maximum of defence, while keeping some pieces positioned such that a quick attack is possible.

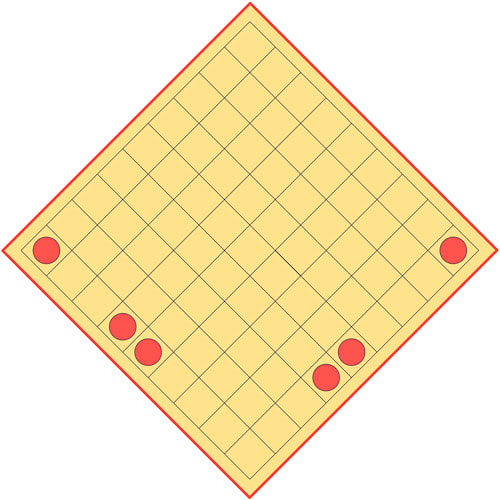

The two corners to either side are strong places to occupy with a Soldier. This creation of a tactically strong place for Soldiers can also happen at the edges of the board with two soldiers.

All comments on strategy concern the game on the larger 9x9 board with the original rules. As mentioned above, the smaller board was the publisher's initiative. I tested the small version many times with other game-buffs. Our opinion was that the game’s strategy was not very different, except that attacking starts immediately and the game moves to the endgame much more quickly than on the larger board.

Although I invented Fenix, I am not a good player because, as is the case with most of my game playing, I play by intuition rather than analysis. Hopefully, nevertheless, I can tell you something of the strategic ideas in the game.

Opening

In the opening the players start to arrange their armies to provide a maximum of defence, while keeping some pieces positioned such that a quick attack is possible.

The two corners to either side are strong places to occupy with a Soldier. This creation of a tactically strong place for Soldiers can also happen at the edges of the board with two soldiers.

However, to come into play and have room for manoeuvring, the Generals need open lines behind the army. Thus, the first and second rows of squares next to the edge of the board have a dual function: as defence lines to keep pieces invulnerable from capture, as well as creating space to get the Generals into play.

Of course, holding your own corner occupied is an easy way for defending your territory. Most first time players use this square for positioning their King, but in reality, it makes your King (one of the strongest pieces on the board) nearly powerless.

Good defence asks for well-built fortifications. A square of four adjacent Soldiers on the board is a stronghold which is capable of responding well when the opponent begins an attack. Each Soldier in the square of four is invulnerable to capture by any piece except the King. An extension of this fortress is a well built defence line!

Good defence asks for well-built fortifications. A square of four adjacent Soldiers on the board is a stronghold which is capable of responding well when the opponent begins an attack. Each Soldier in the square of four is invulnerable to capture by any piece except the King. An extension of this fortress is a well built defence line!

When positioning Generals behind these fortifications, plans can be made for attacking the opponent’s forces. Note, however, that bringing all pieces towards the centre, away from the edges of the board, can allow for a quick destruction!

Middle game

In middle game, players try to attack the opponent’s forces in such a way that for themselves, after capturing moves, a better territorial position is realized on the board. Because capture is compulsory, one of the real tactical features of this game is forcing the opponent to make one or more, captures that are to your advantage. By forcing the opponent to capture, you may be able to respond by capturing more Soldiers or even a General or King. Typically, you offer one of your own pieces to force the opponent into a position that is to your benefit rather than his. Be sure, however, to know which move is the compulsory capture of most pieces

Middle game

In middle game, players try to attack the opponent’s forces in such a way that for themselves, after capturing moves, a better territorial position is realized on the board. Because capture is compulsory, one of the real tactical features of this game is forcing the opponent to make one or more, captures that are to your advantage. By forcing the opponent to capture, you may be able to respond by capturing more Soldiers or even a General or King. Typically, you offer one of your own pieces to force the opponent into a position that is to your benefit rather than his. Be sure, however, to know which move is the compulsory capture of most pieces

Capturing one more Generals in one capture move gives an advantage in addition to material, because the other player loses tempo. However, be careful, because capturing an opponent’s General gives him the possibility to make a new General elsewhere in the next move. This is the really new feature of the game. When losing one or more Generals, the player is allowed to make one new General in the next move from two orthogonally adjacent Soldiers. It is comparable to "dropping" a previously captured piece in Shogi.

Note that it is not compulsory to create a new General when one is captured, and this might be a good plan if a nice multiple-capture is possible.

In middle game, the players try to spread their opponent’s pieces over the board, which makes it much easier to use Generals for capture. Also, when there is more space on the board, the use of the King for captures can be the start of winning the game. The King may be able to approach Soldiers and Generals with impunity for diagonal captures.

When material is low, you may need to make sure you still have adjacent Soldiers in case you need to recreate a General. Likewise, always keep a General with an orthogonally adjacent Soldier for making a new King when you must sacrifice your own King.

Endgame

The endgame is a chase to capture the opposing King. There are many tactical considerations that are similar to those in other checkers-type games, but Fenix has a whole other set of tactics because of the manner in which Generals and the King are reconstituted after capture. I leave it to you to make your own discoveries. The author wishes you, "Good play with Fenix!"

Note that it is not compulsory to create a new General when one is captured, and this might be a good plan if a nice multiple-capture is possible.

In middle game, the players try to spread their opponent’s pieces over the board, which makes it much easier to use Generals for capture. Also, when there is more space on the board, the use of the King for captures can be the start of winning the game. The King may be able to approach Soldiers and Generals with impunity for diagonal captures.

When material is low, you may need to make sure you still have adjacent Soldiers in case you need to recreate a General. Likewise, always keep a General with an orthogonally adjacent Soldier for making a new King when you must sacrifice your own King.

Endgame

The endgame is a chase to capture the opposing King. There are many tactical considerations that are similar to those in other checkers-type games, but Fenix has a whole other set of tactics because of the manner in which Generals and the King are reconstituted after capture. I leave it to you to make your own discoveries. The author wishes you, "Good play with Fenix!"

🔴⚫️🔴⚫️🔴⚫️🔴

Review

by Kerry Handscomb

Originally, I had planned to write a simple review of Fenix, or Strike. However, Fred replied to my questions with such detail that we decided to make his responses the main item. Nevertheless, Fenix is such a good game that it deserves a review, and so here it is.

Fenix is most definitely a combination of Chess and Checkers, because it was precisely designed to appeal both to Chess players and Checkers players by combining elements of both games. Nevertheless, Fenix is not advertised as a combination of Chess and Checkers. It is its own game. Chess is present in the pieces of different powers, and also in its object, effectively to capture the opponent's King—in such a way, however, that a new King cannot be recreated in the defender's next turn. Checkers is present in the capturing rules, and in particular that capturing is compulsory, the source of so many tactical combinations in the checkers games.

Nevertheless, the manner of making Generals and Kings is original and brilliant. The creation and recreation of Generals and Kings by stacking lower-valued pieces has a GIPF-like feel to it. As Fred notes above, HUCH! prioritized republication of the GIPF games over Fenix, although Fenix does compare well in my estimation with the best of the GIPF series. As we can see from Fred's comments, Fenix has a number of interesting strategies that are within fairly easy reach for beginners, guaranteeing that it is a fun game for thoughtful players.

Several tactical and strategical considerations arise immediately from the rules governing the re-instantiation of Generals and Kings, but are not explicit within these rules. I usually think this is the sign of a good design, where the simplicity of a rule belies its significance. For example, a King has to be created from a General, and when a King is created a General disappears. Since there can never be more than three Generals of a colour, the King can only be re-instantiated a maximum of three times, maybe less if a General has already been lost for other reasons. This very fact is a good argument for (almost) always to re-instantiate a General when you can, and (almost) always to keep a pair of orthogonally adjacent Soldiers so that the General can be re-instantiated.

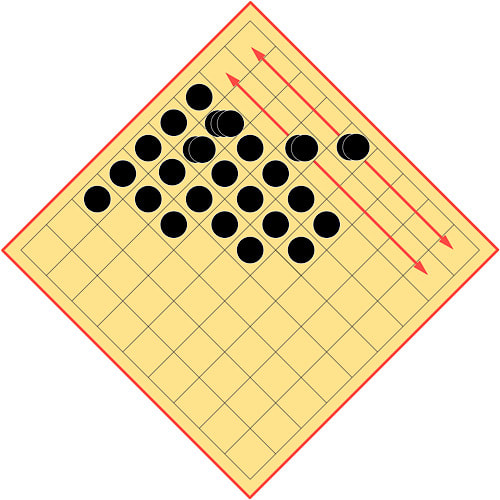

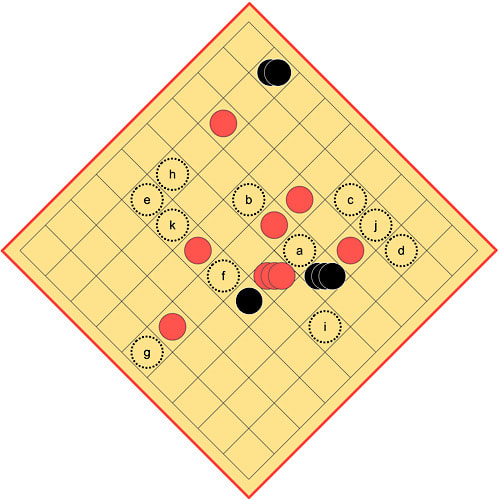

For the opening, Fenix has somewhat of a Chess-like feel, where the armies are disposed for attack and defence and lines are opened for the power-pieces. Perhaps it might be better to have two Generals ranging on one side, as in Figure 5, or better to have one General ranging on one side and one General ranging on the other side—I do not think there is time in the opening before conflict to arrange the army so that all three Generals are able to range freely. These clear strategic options (as well as others, perhaps) are a really nice feature of Fenix.

Like Chess, too, the use of the King as a power-piece in the late middle game and the endgame is interesting. The King is the only piece with the ability to move diagonally, meaning that it can approach and threaten other pieces without necessarily being threatened itself. Many of the interactions between Soldiers and Generals, on the other hand, promise mutual destruction, depending on which side has the tempo. The march of the King on the attack, and its appropriate timing, is a good feature of Fenix.

Aside from these Chess-like aspects of Fenix, the power and beauty of checkers' combinations can be utilized. I am sure that many of the standard tricks and traps of the checkers games are easily portable to Fenix, although I am not well qualified to judge this matter. Nevertheless, many of these tricks and traps rely on the compulsory capture. The compulsory capture is used, of course, to pull pieces out of position from the defensive formations in the corners, at the sides, and in grouped pieces in the centre of the board. It is fun even for a checkers non-expert like myself to sacrifice a Soldier or two for a nice multiple capture. These kinds of manoeuvres are easily within reach for the casual but thoughtful player.

The disputed rule is whether the moves to create Generals and Kings at the beginning of the game need to be between orthogonally adjacent pieces or not. Fred himself prefers the original rule, that the pieces need to be adjacent and that holes in the players' armies will naturally arise. I prefer this rule, too, as I think it naturally provides for a greater variety of strategic options in the opening. This may appear to be paradoxical, because allowing non-adjacent moves means that many more sets of opening moves are possible. Like Fred, I have no clear proof that the original rule will lead to more varied games. However, perhaps the best reason for preferring the original rule is that it logically follows the rules of the rest of the game, where Soldiers can only move one space orthogonally. The "flying" pieces for the setup seem to be out of character with the rest of the game.

I prefer also the 9x9 board. The armies on the 7x8 board start very close, and there is no space for manoeuvring to choose a variety of opening setups—hostilities must occur almost immediately.

Fenix may well be one of the very best of the games that combine elements of Chess and Checkers. Moreover, as I mentioned, Fenix is definitely its own game, and brings something completely new to the table. Of the many games we have been playing, Fenix is one of those rare games that we keep bringing back. We know Fenix will be a fun playing experience by offering a variety of nice tactical and strategical options.

Aside from my own strong recommendation for Fenix, Fred's story of its adoption and longevity in the housing administrative office of the University of Amsterdam is a recommendation in itself that is difficult to top. I wonder if they are still playing Fenix there (calling it "Strike"), and whether succeeding "generations" of office staff are passing it down through the decades?

You can buy HUCH!'s set, which is beautiful. As a bonus, the smaller board is perfect for the game Murus Gallicus, and could almost have been designed for Murus Gallicus. Otherwise, all you need is a 9x9 board and some discs, which would be easy for most gamers to find.

by Kerry Handscomb

Originally, I had planned to write a simple review of Fenix, or Strike. However, Fred replied to my questions with such detail that we decided to make his responses the main item. Nevertheless, Fenix is such a good game that it deserves a review, and so here it is.

Fenix is most definitely a combination of Chess and Checkers, because it was precisely designed to appeal both to Chess players and Checkers players by combining elements of both games. Nevertheless, Fenix is not advertised as a combination of Chess and Checkers. It is its own game. Chess is present in the pieces of different powers, and also in its object, effectively to capture the opponent's King—in such a way, however, that a new King cannot be recreated in the defender's next turn. Checkers is present in the capturing rules, and in particular that capturing is compulsory, the source of so many tactical combinations in the checkers games.

Nevertheless, the manner of making Generals and Kings is original and brilliant. The creation and recreation of Generals and Kings by stacking lower-valued pieces has a GIPF-like feel to it. As Fred notes above, HUCH! prioritized republication of the GIPF games over Fenix, although Fenix does compare well in my estimation with the best of the GIPF series. As we can see from Fred's comments, Fenix has a number of interesting strategies that are within fairly easy reach for beginners, guaranteeing that it is a fun game for thoughtful players.

Several tactical and strategical considerations arise immediately from the rules governing the re-instantiation of Generals and Kings, but are not explicit within these rules. I usually think this is the sign of a good design, where the simplicity of a rule belies its significance. For example, a King has to be created from a General, and when a King is created a General disappears. Since there can never be more than three Generals of a colour, the King can only be re-instantiated a maximum of three times, maybe less if a General has already been lost for other reasons. This very fact is a good argument for (almost) always to re-instantiate a General when you can, and (almost) always to keep a pair of orthogonally adjacent Soldiers so that the General can be re-instantiated.

For the opening, Fenix has somewhat of a Chess-like feel, where the armies are disposed for attack and defence and lines are opened for the power-pieces. Perhaps it might be better to have two Generals ranging on one side, as in Figure 5, or better to have one General ranging on one side and one General ranging on the other side—I do not think there is time in the opening before conflict to arrange the army so that all three Generals are able to range freely. These clear strategic options (as well as others, perhaps) are a really nice feature of Fenix.

Like Chess, too, the use of the King as a power-piece in the late middle game and the endgame is interesting. The King is the only piece with the ability to move diagonally, meaning that it can approach and threaten other pieces without necessarily being threatened itself. Many of the interactions between Soldiers and Generals, on the other hand, promise mutual destruction, depending on which side has the tempo. The march of the King on the attack, and its appropriate timing, is a good feature of Fenix.

Aside from these Chess-like aspects of Fenix, the power and beauty of checkers' combinations can be utilized. I am sure that many of the standard tricks and traps of the checkers games are easily portable to Fenix, although I am not well qualified to judge this matter. Nevertheless, many of these tricks and traps rely on the compulsory capture. The compulsory capture is used, of course, to pull pieces out of position from the defensive formations in the corners, at the sides, and in grouped pieces in the centre of the board. It is fun even for a checkers non-expert like myself to sacrifice a Soldier or two for a nice multiple capture. These kinds of manoeuvres are easily within reach for the casual but thoughtful player.

The disputed rule is whether the moves to create Generals and Kings at the beginning of the game need to be between orthogonally adjacent pieces or not. Fred himself prefers the original rule, that the pieces need to be adjacent and that holes in the players' armies will naturally arise. I prefer this rule, too, as I think it naturally provides for a greater variety of strategic options in the opening. This may appear to be paradoxical, because allowing non-adjacent moves means that many more sets of opening moves are possible. Like Fred, I have no clear proof that the original rule will lead to more varied games. However, perhaps the best reason for preferring the original rule is that it logically follows the rules of the rest of the game, where Soldiers can only move one space orthogonally. The "flying" pieces for the setup seem to be out of character with the rest of the game.

I prefer also the 9x9 board. The armies on the 7x8 board start very close, and there is no space for manoeuvring to choose a variety of opening setups—hostilities must occur almost immediately.

Fenix may well be one of the very best of the games that combine elements of Chess and Checkers. Moreover, as I mentioned, Fenix is definitely its own game, and brings something completely new to the table. Of the many games we have been playing, Fenix is one of those rare games that we keep bringing back. We know Fenix will be a fun playing experience by offering a variety of nice tactical and strategical options.

Aside from my own strong recommendation for Fenix, Fred's story of its adoption and longevity in the housing administrative office of the University of Amsterdam is a recommendation in itself that is difficult to top. I wonder if they are still playing Fenix there (calling it "Strike"), and whether succeeding "generations" of office staff are passing it down through the decades?

You can buy HUCH!'s set, which is beautiful. As a bonus, the smaller board is perfect for the game Murus Gallicus, and could almost have been designed for Murus Gallicus. Otherwise, all you need is a 9x9 board and some discs, which would be easy for most gamers to find.