Game analysis

On February 1, 2020, designer Martijn Althuizen sadly left this world. Martijn was from the Netherlands and only 46 years old. I had some interactions with Martijn regarding his games and he always struck me as someone passionate about his craft and always eager to push the envelope and experiment with new, quirky ideas. He was always polite and available to answer questions and explore suggestions made by anyone interested on his games. With this review, my intent is to honour part of his work and shed a light on his most well-known designs, collectively known as the Tixel family.

A quick search on BoardGameGeek shows those were the designs Martijn spent the most time on, from 2007 to 2019, spanning a total of six games. Although the Tixel series/family is comprised of six members, most would consider only four of them, given they share the most similarities, as well as a publishing/designing evolution of sorts. They are, in order of design: Tix, Tixel, Regatta, and Poka Yoke. An attentive reader may notice that, although Tix is the first in chronological order, it is Tixel that names the family. The reason for this is that "Tixel" is the game that was actually published by Nestorgames, with add-on expansions allowing one to play Tix and Poka Yoke, but not Regatta (for clear reasons below). Therefore, it makes sense from a marketing standpoint to name the series after its flagship game.

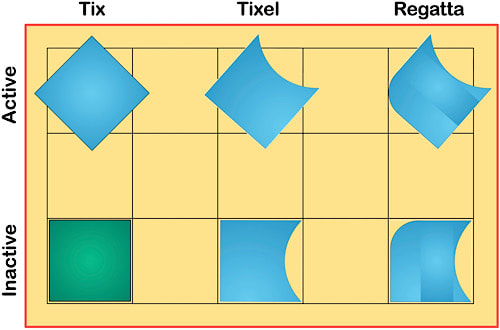

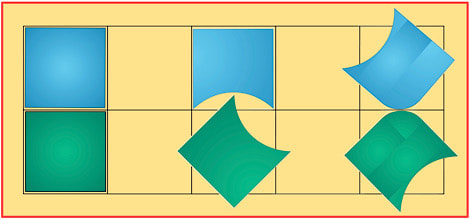

The games are played in a square board of at least 6 spaces per side that may or may not have bounded edges. Bounded edges mean pieces cannot protrude beyond the edge of the board and it is only recommended for board sizes of 8 or larger. The pieces, the star of the show, vary in quantity, variety and shape between games: Tix is played with 8 square pieces (from now on called Tix pieces); Tixel is played with 10 pieces, each of which has one hollow edge (the Tixel pieces); Regatta has 21 pieces, each with one hollow edge and one rounded corner (the Regatta pieces)—see Figure 1. Poka Yoke does not introduce a new type of piece and is played with 10 Tixel pieces but allows two of them to be promoted to Regatta pieces. The interesting thing about the Tixel family is not the shape of the pieces itself, but how Martijn made them interact with the board and each other. A piece adopts two different states: active, which means tilted 45º so its corners are outside the board squares; and inactive, when its sides are aligned with the board squares—see Figure 1. Only an active piece can be slidable (i.e., moved), but this requires it to have the space to do so. This is important, because games effectively end when one player does not have at least one slidable piece, and cannot therefore make a move.

A quick search on BoardGameGeek shows those were the designs Martijn spent the most time on, from 2007 to 2019, spanning a total of six games. Although the Tixel series/family is comprised of six members, most would consider only four of them, given they share the most similarities, as well as a publishing/designing evolution of sorts. They are, in order of design: Tix, Tixel, Regatta, and Poka Yoke. An attentive reader may notice that, although Tix is the first in chronological order, it is Tixel that names the family. The reason for this is that "Tixel" is the game that was actually published by Nestorgames, with add-on expansions allowing one to play Tix and Poka Yoke, but not Regatta (for clear reasons below). Therefore, it makes sense from a marketing standpoint to name the series after its flagship game.

The games are played in a square board of at least 6 spaces per side that may or may not have bounded edges. Bounded edges mean pieces cannot protrude beyond the edge of the board and it is only recommended for board sizes of 8 or larger. The pieces, the star of the show, vary in quantity, variety and shape between games: Tix is played with 8 square pieces (from now on called Tix pieces); Tixel is played with 10 pieces, each of which has one hollow edge (the Tixel pieces); Regatta has 21 pieces, each with one hollow edge and one rounded corner (the Regatta pieces)—see Figure 1. Poka Yoke does not introduce a new type of piece and is played with 10 Tixel pieces but allows two of them to be promoted to Regatta pieces. The interesting thing about the Tixel family is not the shape of the pieces itself, but how Martijn made them interact with the board and each other. A piece adopts two different states: active, which means tilted 45º so its corners are outside the board squares; and inactive, when its sides are aligned with the board squares—see Figure 1. Only an active piece can be slidable (i.e., moved), but this requires it to have the space to do so. This is important, because games effectively end when one player does not have at least one slidable piece, and cannot therefore make a move.

On a player’s turn, the player must either add a piece to the board or slide a slidable piece.

To add a piece, the player must have at least one slidable piece on the board—except, of course, for the first piece that each person places. When adding a piece, it must be placed in an active stance if the spot allows for that. In Tix, a piece can be placed in an active position if there are no orthogonally adjacent squares that are occupied, for otherwise its corner would protrude into an occupied spot. (In Tixel and Regatta, it is possible that a piece can be placed in an active position even if there are adjacent occupied squares, provided the adjacent pieces have the right orientation to allow an active piece to intrude on their square without overlapping.) Pieces can be placed on spots where they must be inactive.

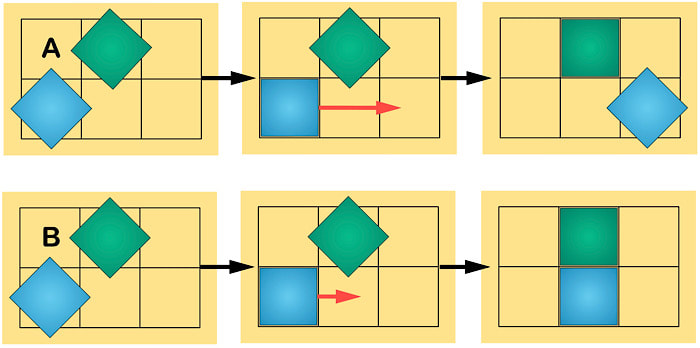

To slide a piece, the piece is moved any number of empty squares orthogonally in a straight line. To slide a piece, a player first pivots the piece to an inactive stance (tilting it by 45º), and then slides it orthogonally to the desired spot, activating it again if possible (Figure 2A). During its sliding movement, it inactivates pieces that it passes next to and may also end up inactive. Active pieces flanking both the sides and end of its movement path are made inactive. In the case the sliding piece becomes inactive, the active player gets an optional bonus move (Figure 2B).

To add a piece, the player must have at least one slidable piece on the board—except, of course, for the first piece that each person places. When adding a piece, it must be placed in an active stance if the spot allows for that. In Tix, a piece can be placed in an active position if there are no orthogonally adjacent squares that are occupied, for otherwise its corner would protrude into an occupied spot. (In Tixel and Regatta, it is possible that a piece can be placed in an active position even if there are adjacent occupied squares, provided the adjacent pieces have the right orientation to allow an active piece to intrude on their square without overlapping.) Pieces can be placed on spots where they must be inactive.

To slide a piece, the piece is moved any number of empty squares orthogonally in a straight line. To slide a piece, a player first pivots the piece to an inactive stance (tilting it by 45º), and then slides it orthogonally to the desired spot, activating it again if possible (Figure 2A). During its sliding movement, it inactivates pieces that it passes next to and may also end up inactive. Active pieces flanking both the sides and end of its movement path are made inactive. In the case the sliding piece becomes inactive, the active player gets an optional bonus move (Figure 2B).

The available bonus moves vary with each game and are the following: ADD a piece to the board, following the standard procedures; SLIDE another piece (with a bonus move if the slid piece ends inactive); REMOVE a friendly piece from the board back to the player’s reserve; ACTIVATE an inactive piece by rotating it, if possible; PIVOT a Tixel or Regatta piece in quarter turn increments; and PROMOTE the first two removed Tixel pieces to Regatta pieces (in Poka Yoke). The game continues turn by turn, with alternating turns, until one player cannot make a move, in which case the player loses. The differences between the games of the family are summarized in the table below.

Feature |

Tix |

Tixel |

Regatta |

Poka Yoke |

Pieces per player |

8 |

10 |

21 |

10 Tixel 2 Regatta |

Board size |

6x6 |

6x6 |

8x8 |

6x6 |

Board edges |

Unbounded |

Unbounded |

Bounded |

Unbounded |

Bonus actions |

|

|

|

|

The play of the games differs as a result of three factors: the type (and number) of pieces, the official size of the board, and whether or not the board edges are bounded. Most interesting for the discussion is the type of piece, since different pieces lead to different bonus-move and tactical possibilities. This is the question I set myself to answer in this essay: How does the shape of the pieces influence gameplay. Since I am most familiar with Tix, and I did not want to play the three other games ad nauseam, I decided to enlist the help of Stephen Tavener’s Ai Ai. Ai Ai is a Java-based general game-playing engine based on Mogal (an earlier system designed and developed by Stephen himself and Cameron Browne). Ai Ai features many games and is capable of generating reports by playing itself over a period of time. Many thanks to Stephen Tavener for allowing me to use his engine, and I cannot stress enough just how powerful a tool Ai Ai is, for abstract game players and designers alike. See the interview with Stephen Tavener in this issue.

In order to see the effect of the pieces, Regatta was set to have the same board settings (6x6, unbounded edges) as the other games. To compensate for this, 6x6 Regatta was arbitrarily set with 15 pieces per player. Although the investigation did not use the same ratio as standard Regatta, one should remember that the Regatta official rules ask for bounded edges, which makes edges more deadly. Bounded edges require a Regatta piece to have its square corner facing inwards, increasing the interaction between pieces; while on an unbounded board, a Regatta piece can be placed with its round corner inwards instead, making it less prone to inactivation. This number of pieces more than satisfied the goal of limiting the draw rate, due to the extra liberties of the pieces (see the table below).

In order to see the effect of the pieces, Regatta was set to have the same board settings (6x6, unbounded edges) as the other games. To compensate for this, 6x6 Regatta was arbitrarily set with 15 pieces per player. Although the investigation did not use the same ratio as standard Regatta, one should remember that the Regatta official rules ask for bounded edges, which makes edges more deadly. Bounded edges require a Regatta piece to have its square corner facing inwards, increasing the interaction between pieces; while on an unbounded board, a Regatta piece can be placed with its round corner inwards instead, making it less prone to inactivation. This number of pieces more than satisfied the goal of limiting the draw rate, due to the extra liberties of the pieces (see the table below).

Aspect |

Tix piece |

Tixel piece |

Regatta piece |

Game length (a) |

36.38 |

48.65 |

38.84 |

Branching factor (b) |

27.05 |

117.17 |

177.97 |

Complexity (log10) (c) |

46.27 |

82.74 |

75.62 |

Board coverage (%) (d) |

52.58 |

46.43 |

59.79 |

First player win (%) |

67.30 |

65.75 |

65.95 |

Draw rate (%) |

4.20 |

5.10 |

0.90 |

(a) Average number of moves in a game (including bonus moves).

(b) Average number of moves in a turn.

(c) Based on game length and branching factor.

(d) Mean average of board locations used per game.

(b) Average number of moves in a turn.

(c) Based on game length and branching factor.

(d) Mean average of board locations used per game.

It is easy to understand why the branching factor is higher in Tixel and Regatta than in Tix: their shapes allow for orientation during placement, while Tix pieces do not. For example, Tixel pieces can be placed with their hollow side facing NW, NE, SW and SE adding 4 options in every single possible active placement. This factor is even more drastic for Regatta pieces, since they also have reflection, totalling 8 active possible orientations.

The changes also affect how the pieces interact with each other. Tix pieces effectively block active pieces being placed in or slid to squares orthogonally adjacent to them, while Tixel pieces can be placed or slid in an inactive state with their hollow side facing the active piece, and Regatta pieces can be active if both pieces have their rounded corners facing each other (Figure 3).

The changes also affect how the pieces interact with each other. Tix pieces effectively block active pieces being placed in or slid to squares orthogonally adjacent to them, while Tixel pieces can be placed or slid in an inactive state with their hollow side facing the active piece, and Regatta pieces can be active if both pieces have their rounded corners facing each other (Figure 3).

Where pieces can interact more, the game length should increase, if stalemating your opponent is the goal. In addition, it makes the game less decisive, since it is easier to find active placements and slides that are undisturbed by other pieces. What was observed is that Tix and Regatta shared a similar game length, both smaller than Tixel. The results for Tix were as expected, but not for Regatta. Regatta’s shorter games (than Tixel) might be due to the more forgiving shape of Regatta pieces—they allow for easier reactivation after slides, limiting the number of bonus moves. A lot of the length comes from bonus moves, since Ai Ai counts them just like regular moves. The higher interaction of Regatta pieces justifies the higher board coverage in this game, but not in Tixel. Tixel showed more bonus moves than Tix, meaning more opportunities to remove pieces, probably reducing board coverage in this game.

Games showed a bias towards the first player, with a 67.30, 65.75 and 65.95% win rate in 6x6 Tix, Tixel, and Regatta, respectively. (Note: standard Regatta also has a first player bias of 61.60%). Firstly, it is always important to highlight that win/loss statistics may vary depending on thinking time (the horizon effect, etc.), bad heuristics, bugs, and other factors, so they should be taken with a pinch of salt. However, win/loss statistics can be used to indicate how suitable the game is for competitive play between non-perfect human players. As usual, one can consider using the pie rule, but it would take a substantial number of recorded games to find a first move that would result in balanced chances, so I am not confident in providing a possible balancing first move.

Another balancing option is playing two games with alternating positions. I believe this is only an option if the game has a built-in scoring system, which the Tixel family lacks. A possible quantitative measure to gauge success could be how many tempi the winner has after stalemating their opponent, which would be the number of slidable pieces on the board plus remaining pieces in their reserve after winning the game. It is possible for a game to end with the loser having more pieces in reserve than the winner (if the loser focuses more on moving than placing), in which case it might be better to reward the winner points equal to slidable pieces on board plus total number of pieces in both players' reserves. That may mean shifting the game more towards a placement game, which the designer disliked (something we discussed years ago), because it would take the focus away from what he thought was the most interesting aspect of the game: "en passant” inactivations and combinations.

As an exercise, I tried another approach. I set unbounded 6x6 Tix and Tixel with the second player owning an extra piece. My reasoning was that this off-board material advantage could offset what might be the first player’s advantage of an early presence on the board. That seemed to work for both games: the first player won 53.20% and 59.70% of the games in Tix and Tixel, respectively (instead of the nearly 67% and 65% with the standard rules). A following report showed Tixel could be further improved with a second extra black piece, the first player winning 56.75% of the games with this setting (with the collateral effect of reducing draws by half—see the argument below). I leave Regatta’s and Poka Yoke’s improvement to the reader.

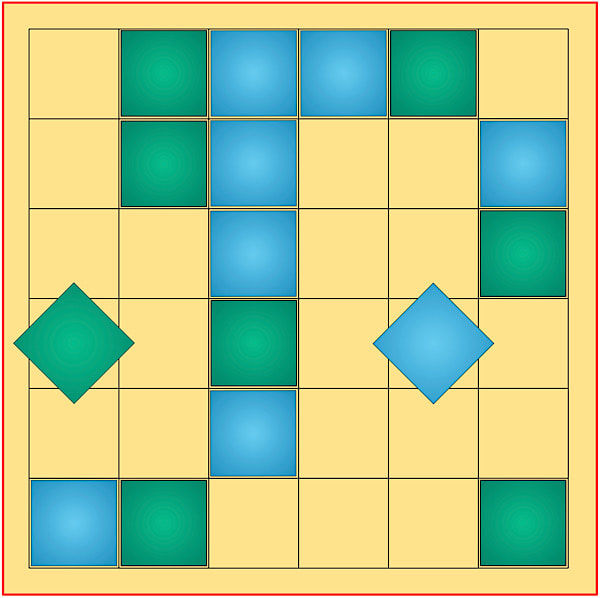

By the rules, it is not possible to draw in the sense of a tie, so the tie results found by Ai Ai are games that were abandoned after a certain number of moves (according to Stephen, this amount is set to 512 moves at present). This is a consequence of gameplay. At the beginning of the game, players jockey for protective positions for their pieces and, after some inactivation exchanges, defensive pockets where players can slide pieces back and forth naturally occur. See Figure 4, where Green and Blue can both move their active pieces one space up and down indefinitely.

Games showed a bias towards the first player, with a 67.30, 65.75 and 65.95% win rate in 6x6 Tix, Tixel, and Regatta, respectively. (Note: standard Regatta also has a first player bias of 61.60%). Firstly, it is always important to highlight that win/loss statistics may vary depending on thinking time (the horizon effect, etc.), bad heuristics, bugs, and other factors, so they should be taken with a pinch of salt. However, win/loss statistics can be used to indicate how suitable the game is for competitive play between non-perfect human players. As usual, one can consider using the pie rule, but it would take a substantial number of recorded games to find a first move that would result in balanced chances, so I am not confident in providing a possible balancing first move.

Another balancing option is playing two games with alternating positions. I believe this is only an option if the game has a built-in scoring system, which the Tixel family lacks. A possible quantitative measure to gauge success could be how many tempi the winner has after stalemating their opponent, which would be the number of slidable pieces on the board plus remaining pieces in their reserve after winning the game. It is possible for a game to end with the loser having more pieces in reserve than the winner (if the loser focuses more on moving than placing), in which case it might be better to reward the winner points equal to slidable pieces on board plus total number of pieces in both players' reserves. That may mean shifting the game more towards a placement game, which the designer disliked (something we discussed years ago), because it would take the focus away from what he thought was the most interesting aspect of the game: "en passant” inactivations and combinations.

As an exercise, I tried another approach. I set unbounded 6x6 Tix and Tixel with the second player owning an extra piece. My reasoning was that this off-board material advantage could offset what might be the first player’s advantage of an early presence on the board. That seemed to work for both games: the first player won 53.20% and 59.70% of the games in Tix and Tixel, respectively (instead of the nearly 67% and 65% with the standard rules). A following report showed Tixel could be further improved with a second extra black piece, the first player winning 56.75% of the games with this setting (with the collateral effect of reducing draws by half—see the argument below). I leave Regatta’s and Poka Yoke’s improvement to the reader.

By the rules, it is not possible to draw in the sense of a tie, so the tie results found by Ai Ai are games that were abandoned after a certain number of moves (according to Stephen, this amount is set to 512 moves at present). This is a consequence of gameplay. At the beginning of the game, players jockey for protective positions for their pieces and, after some inactivation exchanges, defensive pockets where players can slide pieces back and forth naturally occur. See Figure 4, where Green and Blue can both move their active pieces one space up and down indefinitely.

These kinds of draws are reflected in Tix and Tixel, which have around 5% of drawn games each. Regatta does not have so many draws, because of the number of pieces I set to each player—the amount was high enough that players could slowly chip away at the safe spots of their opponents, squeezing the active pieces until they could no longer move (even considering unbounded edges). Other simulations (data not shown) showed a greater than 10% draw rate in unbounded 8x8 Tix and Tixel, as well as in standard Regatta. I do not personally mind a 5% draw rate, but for the more draw-adverse out there, the most logical solution is to add more pieces to a player’s reserve. For example, in Figure 4, an extra piece would give a victory to the player moving last. I suspect one or two pieces will be enough in 6x6 Tix and Tixel, while unbounded 8x8 Tix and Tixel and standard Regatta would benefit from 2 to 4 more pieces. Again, this would mean a shift towards more placements, which Martijn was not fond of. In case an extra piece is not available, a threefold repetition or Ko rule may be warranted.

Statistics aside, the game feels quite tactical, with players jockeying for position and trying to create safe spots. At the beginning, players spread pieces and try to create formations to avoid their pieces being inactivated by slides. As the game progresses, it is hard to avoid inactivation opportunities and inactive pieces start to clog the board, making it hard to find placements as well as creating some safe spots. The endgame is a matter of saving tempo and chipping away the opponent’s safe spots, making the opponent spend reserves until forced to move the last active piece. Aside from the shape of the pieces, the possibility of several extra turns, in the form of bonus moves, is one of the most interesting traits of this game. To find a string of bonus slides that allow you to inactivate several opponent's pieces, shifting the game into your favour, is akin to the opportunity to set off a brilliant multiple capture move in Checkers.

For those that really like puzzly, tactical games, I recommend the Tixel family. It is different from almost anything that I have seen in terms of abstract games and engages players in a different way. The piece tweaks create more rules that definitely add complexity and choices, but also cause a certain amount of analysis-paralysis. Also, they add some decisions during placement that I feel are too opaque: I find it hard to visualize the consequences further down the road of such and such way of placing a piece. This is exacerbated in Regatta, given the complexity of the pieces and considering the standard board for this game is 8x8. Because of that, the best order to learn the games are Tix, Tixel, Poka Yoke, and lastly Regatta. I know I did not discuss Poka Yoke, mostly because I was focusing on the type (instead of the variety) of pieces, but the game might be a good middle ground between Tixel and Regatta. Caveat: Poka Yoke also had a first player bias (67.50%), so adjustments of the number of pieces (and/or possibly the number of promotions) could be explored—though not by me!

Conclusions

In a more personal note, it is my hope this review and analysis has shown readers a little of Martijn’s work. Believe it or not, he designed even more unusual games throughout his short life, and readers are encouraged to explore some of those games. Not only his death, but Eric Solomon’s (author of Hyle, Billabong, Black box, among others) and Rich Gowell’s (designer of Entrapment) made this a sad year for abstract game enthusiasts. Martijn and Rich, in particular, were members of the BoardGameGeek forum, and we often had discussions in the Abstract Games sub-forum, which make their deaths more impactful to me. To all of them, rest in peace.

Statistics aside, the game feels quite tactical, with players jockeying for position and trying to create safe spots. At the beginning, players spread pieces and try to create formations to avoid their pieces being inactivated by slides. As the game progresses, it is hard to avoid inactivation opportunities and inactive pieces start to clog the board, making it hard to find placements as well as creating some safe spots. The endgame is a matter of saving tempo and chipping away the opponent’s safe spots, making the opponent spend reserves until forced to move the last active piece. Aside from the shape of the pieces, the possibility of several extra turns, in the form of bonus moves, is one of the most interesting traits of this game. To find a string of bonus slides that allow you to inactivate several opponent's pieces, shifting the game into your favour, is akin to the opportunity to set off a brilliant multiple capture move in Checkers.

For those that really like puzzly, tactical games, I recommend the Tixel family. It is different from almost anything that I have seen in terms of abstract games and engages players in a different way. The piece tweaks create more rules that definitely add complexity and choices, but also cause a certain amount of analysis-paralysis. Also, they add some decisions during placement that I feel are too opaque: I find it hard to visualize the consequences further down the road of such and such way of placing a piece. This is exacerbated in Regatta, given the complexity of the pieces and considering the standard board for this game is 8x8. Because of that, the best order to learn the games are Tix, Tixel, Poka Yoke, and lastly Regatta. I know I did not discuss Poka Yoke, mostly because I was focusing on the type (instead of the variety) of pieces, but the game might be a good middle ground between Tixel and Regatta. Caveat: Poka Yoke also had a first player bias (67.50%), so adjustments of the number of pieces (and/or possibly the number of promotions) could be explored—though not by me!

Conclusions

- Avoid large board sizes, they increase the number of draws (unless using extra pieces to account for that).

- An uneven number of pieces offsets the first player advantage. One extra black piece is enough for 6x6 Tix; two improve 6x6 Tixel.

- Unbounded 6x6 Regatta seems to be viable (in terms of draws), although some tests are required to find a number of pieces that could offset player bias.

- I still prefer Tix, and could see myself going for Tixel, but not 8x8 Regatta.

- Ai Ai is awesome.

In a more personal note, it is my hope this review and analysis has shown readers a little of Martijn’s work. Believe it or not, he designed even more unusual games throughout his short life, and readers are encouraged to explore some of those games. Not only his death, but Eric Solomon’s (author of Hyle, Billabong, Black box, among others) and Rich Gowell’s (designer of Entrapment) made this a sad year for abstract game enthusiasts. Martijn and Rich, in particular, were members of the BoardGameGeek forum, and we often had discussions in the Abstract Games sub-forum, which make their deaths more impactful to me. To all of them, rest in peace.

Header image

Craft-store glass mosaic tiles on a 6''x6'' board printed on aluminum.

Craft-store glass mosaic tiles on a 6''x6'' board printed on aluminum.