Solitaire abstract games

Spiral is a game developed by Raymond Gallardo in 2016. Actually, it is a pair of games, a trick-taking and connection game for two players, and a card-solitaire and connection game for one player. The author refers to the former as The Gift and the latter as Grazing. Since we are concerned here only with the solitaire game, I will refer to it simply as "Spiral." Despite the use of the card layout, at heart Spiral is a solitaire connection game rather than a card solitaire. The AI opponent is well designed and formidable. The author dubs her Dr. Harriet Brooks after the Canadian nuclear physicist.

Rules

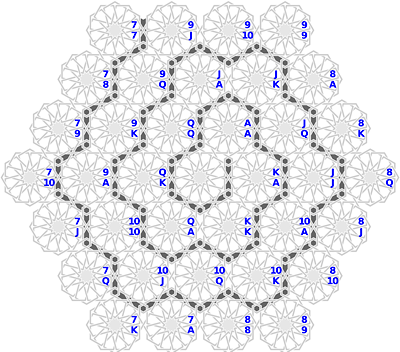

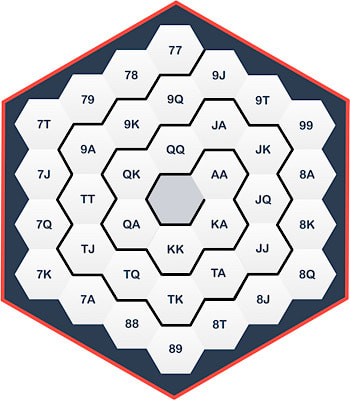

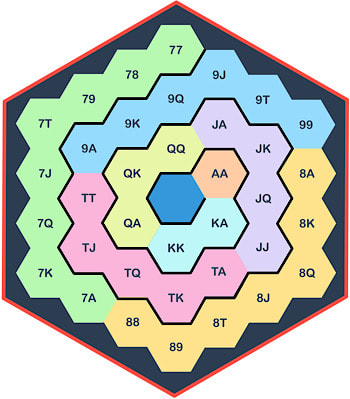

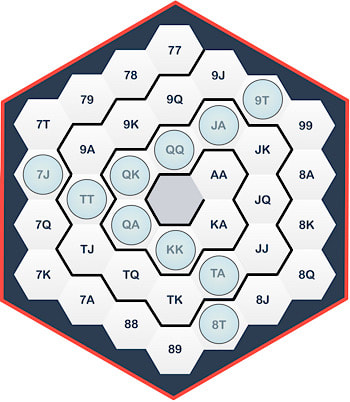

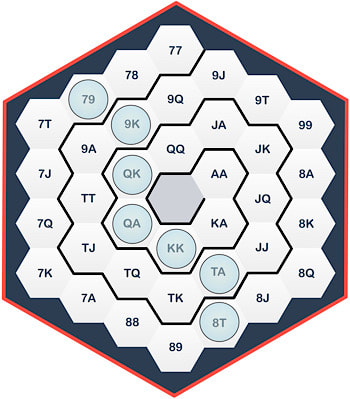

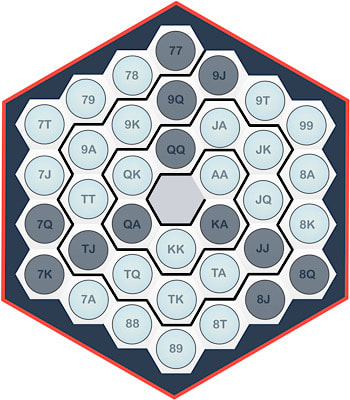

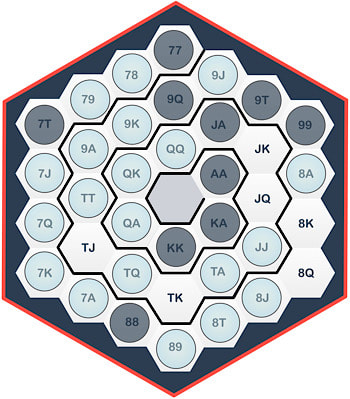

The board is a base 4 hex-hex board, containing 37 spaces. Each space, except for the centre space, is marked with a pair of letters or numbers, corresponding to the card values: 7, 8, 9, Ten, Jack, Queen, King, Ace. All 36 possible combinations of pairs of values are used. The designations of the spaces are arranged in a spiral pattern, as shown in Figures 1 and 2 and the header image, which gives the game its name.

Figure 1 shows my design, and Figure 2 is the same design with some colour coding, which may make it easier to locate specific spaces quickly. PDF files of these two designs are available here and here, respectively. The header shows the author's own beautiful and intricate design, available here, and the reader can choose which of the three is preferable.

Rules

The board is a base 4 hex-hex board, containing 37 spaces. Each space, except for the centre space, is marked with a pair of letters or numbers, corresponding to the card values: 7, 8, 9, Ten, Jack, Queen, King, Ace. All 36 possible combinations of pairs of values are used. The designations of the spaces are arranged in a spiral pattern, as shown in Figures 1 and 2 and the header image, which gives the game its name.

Figure 1 shows my design, and Figure 2 is the same design with some colour coding, which may make it easier to locate specific spaces quickly. PDF files of these two designs are available here and here, respectively. The header shows the author's own beautiful and intricate design, available here, and the reader can choose which of the three is preferable.

Since you still need to see the space designations, even when the spaces are occupied, you must use transparent counters (or something similar) with my designs—which are cheaply and easily available from stores that sell learning resources. The author's own designations are off to the side of each space, meaning that transparent counters are not necessary. You need 13 counters for yourself and 24 counters of a different colour for Dr. Brooks. Lastly, you need a 32-card deck, sometimes referred to as a Piquet deck, in which card ranks from 2 to 6 have been removed from a regular deck.

The board starts empty. You shuffle the deck and deal the cards face up in four columns of eight cards each, as shown in the sample position in Figure 7, below.

You and Dr. Brooks alternate turns. You move first. For your first and subsequent turns, you select a pair of cards, one from the bottom of one of the four columns, and one from the bottom of another of the four columns. Place a piece on the board in the space indicated by the pair of cards you have chosen. If that space is occupied, place a piece in the next vacant space, moving down the spiral towards the outside of the board; if all spaces in that direction are occupied, then place a piece in the next vacant space moving up the spiral towards the centre of the board. After the move, place the pair of cards in a discard pile.

Dr. Brooks places two pieces each turn, one according to the pair of cards at the bottom of the first two columns, one according to the pair of cards at the bottom of the last two columns. The rules regarding placement of pieces on occupied spaces are the same: go down the spiral towards the outside, and if all spaces towards the outside are occupied, move up the spiral towards the centre. Pairs of cards are placed in the discard pile as they are used.

If after your turn or Dr. Brooks' turn one or more of the columns of cards has been emptied, then shuffle any remaining cards in the layout together with all the discards, and deal the cards out again to form four columns of eight cards each. In a typical game, you will have to deal the cards three times, with three different layouts, and the game should finish fairly quickly into the third layout. If one of the first two columns is emptied with Dr. Brooks' move, then complete her turn with the last two columns before redealing the cards.

You win immediately if your pieces on the board form a fork, joining three non-adjacent sides of the board, as shown in Figure 3. You lose immediately if your pieces on the board form a bridge, joining two opposite sides of the board, as shown in Figure 4. If your move creates a fork and a bridge simultaneously, you win. Dr. Brooks wins immediately if her pieces form either a fork or a bridge. In addition to the two moves on a turn, Dr. Brooks has easier winning conditions! Note that corner pieces belong to both sides that they connect, as with Hex.

The board starts empty. You shuffle the deck and deal the cards face up in four columns of eight cards each, as shown in the sample position in Figure 7, below.

You and Dr. Brooks alternate turns. You move first. For your first and subsequent turns, you select a pair of cards, one from the bottom of one of the four columns, and one from the bottom of another of the four columns. Place a piece on the board in the space indicated by the pair of cards you have chosen. If that space is occupied, place a piece in the next vacant space, moving down the spiral towards the outside of the board; if all spaces in that direction are occupied, then place a piece in the next vacant space moving up the spiral towards the centre of the board. After the move, place the pair of cards in a discard pile.

Dr. Brooks places two pieces each turn, one according to the pair of cards at the bottom of the first two columns, one according to the pair of cards at the bottom of the last two columns. The rules regarding placement of pieces on occupied spaces are the same: go down the spiral towards the outside, and if all spaces towards the outside are occupied, move up the spiral towards the centre. Pairs of cards are placed in the discard pile as they are used.

If after your turn or Dr. Brooks' turn one or more of the columns of cards has been emptied, then shuffle any remaining cards in the layout together with all the discards, and deal the cards out again to form four columns of eight cards each. In a typical game, you will have to deal the cards three times, with three different layouts, and the game should finish fairly quickly into the third layout. If one of the first two columns is emptied with Dr. Brooks' move, then complete her turn with the last two columns before redealing the cards.

You win immediately if your pieces on the board form a fork, joining three non-adjacent sides of the board, as shown in Figure 3. You lose immediately if your pieces on the board form a bridge, joining two opposite sides of the board, as shown in Figure 4. If your move creates a fork and a bridge simultaneously, you win. Dr. Brooks wins immediately if her pieces form either a fork or a bridge. In addition to the two moves on a turn, Dr. Brooks has easier winning conditions! Note that corner pieces belong to both sides that they connect, as with Hex.

And that is all there is to the rules. It makes for a fairly challenging solitaire, in which I can win maybe one in three attempts. I suspect that with good play, you ought to be able to beat Dr. Brooks more often than not, although I have yet to reach that level of skill.

Some observations

The centre space cannot be reached directly with any pair of cards. A little thought will demonstrate that the centre space only becomes occupied after all other spaces are full.

Each pair of turns results in three pieces being placed on the board, one of yours and two of Dr. Brooks'. Therefore, if 36 spaces are occupied, except for the centre, then it must be your turn to place the 37th, in the centre, which will decide the game. It is quite possible for the game to last this long, as shown in Figure 5.

Some observations

The centre space cannot be reached directly with any pair of cards. A little thought will demonstrate that the centre space only becomes occupied after all other spaces are full.

Each pair of turns results in three pieces being placed on the board, one of yours and two of Dr. Brooks'. Therefore, if 36 spaces are occupied, except for the centre, then it must be your turn to place the 37th, in the centre, which will decide the game. It is quite possible for the game to last this long, as shown in Figure 5.

Inability to occupy the centre space any earlier means that winning positions before the board is full must detour around the centre. It seems to be a good idea to aim to occupy several several central spaces early in game, before Dr. Brooks can close down your options to go around the centre. On the other hand, if Dr. Brooks is moving to occupy all four spaces along an edge, it is good to get one of your pieces on that edge to keep your options open. Corner spaces are at a premium, as each one gives you a foothold on two sides.

Theoretically, it is possible to look at the initial layout of cards and plan fully your moves for the early part of the game. However, I find it difficult to look that deeply into the game, and often I move according to which pair of cards seems to give me the better move, without much analysis of the full layout. However, the first deal of the cards typically accounts for less than half of the game. Towards the end of the second deal, I might start looking at what is coming up next from Dr. Brooks, in case she has a strong move. Definitely at the start of the third deal, I will be doing more analysis, trying to plan for a win. The sample position below demonstrates the type of thinking required at this stage of the game.

Sample position

Figure 6 shows the beginning of the third deal, and Figure 7 shows the current position on the board.

Theoretically, it is possible to look at the initial layout of cards and plan fully your moves for the early part of the game. However, I find it difficult to look that deeply into the game, and often I move according to which pair of cards seems to give me the better move, without much analysis of the full layout. However, the first deal of the cards typically accounts for less than half of the game. Towards the end of the second deal, I might start looking at what is coming up next from Dr. Brooks, in case she has a strong move. Definitely at the start of the third deal, I will be doing more analysis, trying to plan for a win. The sample position below demonstrates the type of thinking required at this stage of the game.

Sample position

Figure 6 shows the beginning of the third deal, and Figure 7 shows the current position on the board.

Thirty pieces have been placed on the board, a multiple of three, and it is your move. We can see that the key space now is the TK, and whoever manages to occupy this space will win. The TK space can be reached through three possible pairs of cards, JJ, TA, and of course TK itself. Looking at the card layout, the clearest access to one of these pairs is the ♣A together with either ♥T or ♣T. So, if you play ♣Q together with either ♠9 or ♠8, Dr. Brooks will necessarily uncover a TA combination for you with her move. This is the fastest and surest way to win, but are there any other winning moves?

Let us look at the game now as a war of attrition, where the players take turns to fill in non-crucial spaces. The longest sequence of moves will be You - Dr. Brooks - You - Dr. Brooks. If the game lasts that long, with neither player occupying the crucial TK, then at last, Dr. Brooks must get it. You do not have a winning move immediately, and therefore, your winning move must occur in your next move, before Dr. Brooks gets the TK. You cannot win a war of attrition!

So, for the analysis, imagine what Dr. Brooks' move is after each of your possible immediate moves. You must have a winning move after Dr. Brooks' next move, for otherwise you will lose. A little further scrutiny shows that only ♠9♣Q or ♠8♣Q gives the required winning move.

Conclusion

This example above demonstrates the kind of thinking needed to play Spiral successfully. Spiral is an interesting game, requiring some strategic thinking early on and accurate tactical analysis towards the end of a game. Spiral is very unusual in that it is a solitaire connection game. It should be easy for most gamers to put together a set. I highly recommend Spiral—and after the solitaire you can try the excellent two-player trick-taking game!

Let us look at the game now as a war of attrition, where the players take turns to fill in non-crucial spaces. The longest sequence of moves will be You - Dr. Brooks - You - Dr. Brooks. If the game lasts that long, with neither player occupying the crucial TK, then at last, Dr. Brooks must get it. You do not have a winning move immediately, and therefore, your winning move must occur in your next move, before Dr. Brooks gets the TK. You cannot win a war of attrition!

So, for the analysis, imagine what Dr. Brooks' move is after each of your possible immediate moves. You must have a winning move after Dr. Brooks' next move, for otherwise you will lose. A little further scrutiny shows that only ♠9♣Q or ♠8♣Q gives the required winning move.

Conclusion

This example above demonstrates the kind of thinking needed to play Spiral successfully. Spiral is an interesting game, requiring some strategic thinking early on and accurate tactical analysis towards the end of a game. Spiral is very unusual in that it is a solitaire connection game. It should be easy for most gamers to put together a set. I highly recommend Spiral—and after the solitaire you can try the excellent two-player trick-taking game!

Variants

To make the game slightly easier, you may choose the bottom two cards of one column. If you prefer solitaire games with no random elements other than the initial deal (like FreeCell), then instead of discarding cards, move used cards to the top of their respective columns. To save table space, place used cards face down in a stack above the column. Once the column is empty, flip the stack face up and spread it downwards into a column. With this variant, you essentially “reset” a column of cards to its initial state once you’ve played all the cards in it.

Designer notes

The author, Raymond Gallardo, a technical writer from Montreal, makes the following comments about the development of Spiral:

To make the game slightly easier, you may choose the bottom two cards of one column. If you prefer solitaire games with no random elements other than the initial deal (like FreeCell), then instead of discarding cards, move used cards to the top of their respective columns. To save table space, place used cards face down in a stack above the column. Once the column is empty, flip the stack face up and spread it downwards into a column. With this variant, you essentially “reset” a column of cards to its initial state once you’ve played all the cards in it.

Designer notes

The author, Raymond Gallardo, a technical writer from Montreal, makes the following comments about the development of Spiral:

"One of the main design goals for Spiral was combine two of my favourite gaming genres: trick-taking and abstract connection games. Initial prototypes involved labelling every space of a connection game’s board (for example, the rhombic board of Hex) with a playing card. When you win a trick, you place a stone in every space corresponding to the cards you won in the trick. This was not fun, as players would spend too much time locating which card corresponded to which space on the board, slowing down the game too much. To reduce the amount of this cross referencing, I labelled each space with the cards that a trick could contain, minus the suits. But that limited me to a two-player trick taking game—there would be too many possibilities with three or more cards. As for which connection game to use, I opted for Cameron Brown’s Cross and its hex-hex board mostly for aesthetic reasons; a hex-hex board fits on a letter-sized sheet of paper better than a triangular or rhombic one!

"The solo rules of Spiral were an afterthought. I realized that players could claim spaces by simply drafting them from a bunch of face-up cards. I thought of Sid Sackson’s game Suit Yourself where players would draft cards from the bottom of face-up columns of cards. Then I thought of Cross’s predecessor, Jorge Gomez Arrausi’s Unlur, which has different, unbalanced objectives for each player: one has to connect two opposite sides, the other has to connect three non-adjacent sides. What is really cool about unbalanced objectives is that I could play with this imbalance by tinkering with other elements of the game, such as picking who gets what objective and the number of pieces a player may place during a turn."