Vintage games

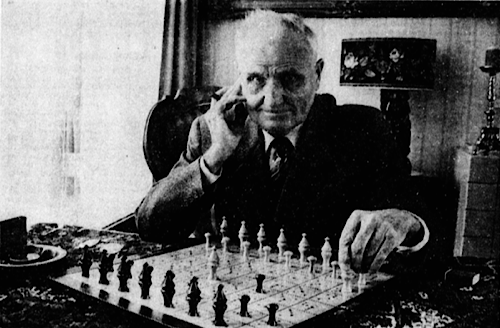

On June 24, 1974 the daily newspaper De Tijd published an article about Jan Boogerd from Rotterdam, inventor of "De grootste denkmeter ter wereld [The greatest measure of thought in the world]"—in Boogerd’s own words. At the time, Jan Boogerd was 77 years old, and he gave a contact address in Rotterdam so that potential publishers of his latest invention, a dexterity-game for children, could easily contact him. Boogerd is quoted as saying, he was pleased that a game manufacturer had bought Schada, and he thought Schada would be in the shops that autumn. As it happened, Schada was not republished at that time. Nevertheless, Schada has an interesting earlier history spanning World War II, which is the topic of this investigation.

I started my research into Schada and its inventor in the the early 1980's. At the time, I had no knowledge of the De Tijd article. I had a copy of the game, I knew about its inventor, J. Boogerd of Rotterdam, and I wanted to know more about the history of Schada and its development. The first step, searching through the telephone directory of Rotterdam, did not lead to any clues about Boogerd. More research into his personal life was blocked by the Dutch privacy laws, which give only relatives the opportunity to explore official files and archives. Thus, only a very limited history of the game Schada was possible at that time.

Decades later, in 2015, I continued my research, and I uncovered more information about J. Boogerd, because his name and other data were put into an online genealogy registration. Thus, Jan Boogerd was born on April 10, 1897 in Goes, a small town in the Dutch province of Zeeland; he died in Rotterdam on November 2, 1985; he married Pieternella van der Doe, and the couple had two sons; in 1940, the family lived in West Rotterdam.

Around the same time, I discovered the De Tijd article, and one more article from February 19, 1974 in the newspaper Nieuwsblad van het Noorden. Suddenly, there was more background information available than at the time of my first research in the 1980's.

Subsequently, I started investigating patents. In those days, the Dutch Patent Office was available and open to the public each day. After spending a whole day there, I had identified all the available patent information on Schada.

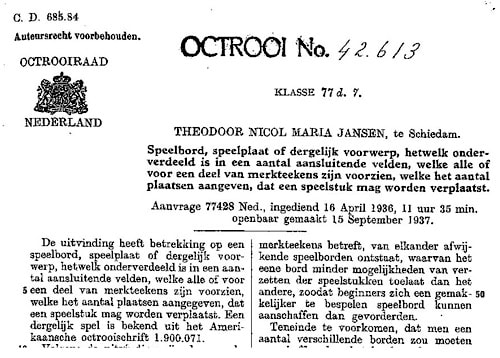

The De Tijd article referred to a patent number identified by Boogerd as 77428. Actually, 77428 is a request number; the real patent number was 42.613. The Dutch patent is shown below, and as you can see, it is held by Theodoor Nicol Maria Jansen of Schiedam, and dated April 16, 1936. Note, however, that this patent is for a game board only, and not for the game of Schada.

I started my research into Schada and its inventor in the the early 1980's. At the time, I had no knowledge of the De Tijd article. I had a copy of the game, I knew about its inventor, J. Boogerd of Rotterdam, and I wanted to know more about the history of Schada and its development. The first step, searching through the telephone directory of Rotterdam, did not lead to any clues about Boogerd. More research into his personal life was blocked by the Dutch privacy laws, which give only relatives the opportunity to explore official files and archives. Thus, only a very limited history of the game Schada was possible at that time.

Decades later, in 2015, I continued my research, and I uncovered more information about J. Boogerd, because his name and other data were put into an online genealogy registration. Thus, Jan Boogerd was born on April 10, 1897 in Goes, a small town in the Dutch province of Zeeland; he died in Rotterdam on November 2, 1985; he married Pieternella van der Doe, and the couple had two sons; in 1940, the family lived in West Rotterdam.

Around the same time, I discovered the De Tijd article, and one more article from February 19, 1974 in the newspaper Nieuwsblad van het Noorden. Suddenly, there was more background information available than at the time of my first research in the 1980's.

Subsequently, I started investigating patents. In those days, the Dutch Patent Office was available and open to the public each day. After spending a whole day there, I had identified all the available patent information on Schada.

The De Tijd article referred to a patent number identified by Boogerd as 77428. Actually, 77428 is a request number; the real patent number was 42.613. The Dutch patent is shown below, and as you can see, it is held by Theodoor Nicol Maria Jansen of Schiedam, and dated April 16, 1936. Note, however, that this patent is for a game board only, and not for the game of Schada.

On February 15, 1938 an identical patent was filed by Firma Groenteman & Co. of Amsterdam, shown below. The same company registered the same text and drawings on April 30, 1938 as patent number 426980 in Belgium.

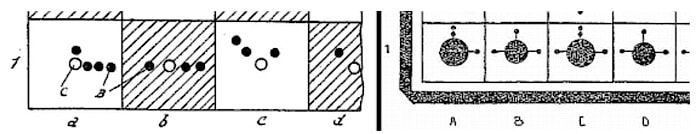

These various, but essentially identical, patents show a game board, where the board spaces are marked with circles and lines indicating movement directions. As noted above, the patents do not describe the game Schada itself, but rather the Schada game equipment.

How did the game Schada develop out of this board idea? In the De Tijd article Boogerd claims says that he purchased rights to the game before the War, while admitting that the patent had expired. Actually, Boogerd claims “author’s rights” to the game in the De Tijd article, rather than ownership of the patent, which implies that Boogerd is the game’s designer. Boogerd must have developed the game Schada, based on Theodoor Nicol Maria Jansen's original game board patent. A reasonable guess is that Firma Groenteman & Co. of Amsterdam acquired the patent, and subsequently asked Boogerd to develop a game on the basis of the board.

Boogerd says in the De Tijd article that he first named the game "Janbo" (after himself!), but soon thereafter chose the name Schada, from schaak and damspel, the Dutch words for Chess and Checkers, respectively.

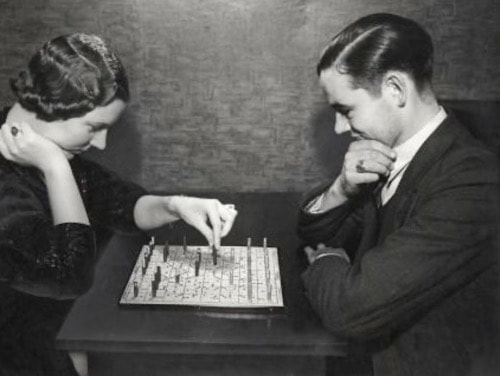

Actually, an identical game called Schaakdam was published in 1936 by Schilte & Zonen of Ysselsteyn. In the photoarchives of the printing company Spaarnestad of Haarlem, some photographs of this version have survived, and one is shown below. The Schaakdam material states only, "Alle rechten voorbehouden" [All rights reserved], with no indication of the author or any patent application. We must suppose it is Boogerd's game with a different name. In any case, it pushes the design of the game back to the year of the original patent for the board.

Boogerd says in the De Tijd article that he first named the game "Janbo" (after himself!), but soon thereafter chose the name Schada, from schaak and damspel, the Dutch words for Chess and Checkers, respectively.

Actually, an identical game called Schaakdam was published in 1936 by Schilte & Zonen of Ysselsteyn. In the photoarchives of the printing company Spaarnestad of Haarlem, some photographs of this version have survived, and one is shown below. The Schaakdam material states only, "Alle rechten voorbehouden" [All rights reserved], with no indication of the author or any patent application. We must suppose it is Boogerd's game with a different name. In any case, it pushes the design of the game back to the year of the original patent for the board.

Nevertheless, the available information is not clear about the nature and the timing of the cooperation between Boogerd and Firma Groenteman & Co. The owner of the company, Mr. Groenteman himself, was chairman of Den Amsterdamschen Dambond [The Amsterdam Checkers Society]. Did Groenteman ask Boogerd to invent a game after buying the patent, or did Boogerd contact Groentman after the first venture with Schilte & Zonen? We do not know.

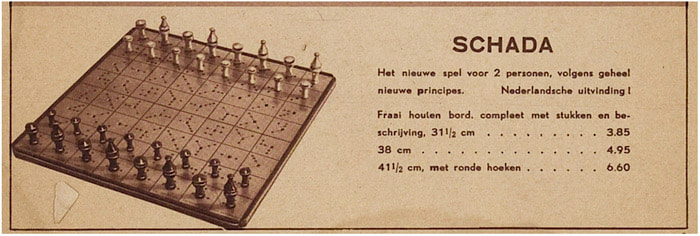

In these years just before the War, when Schada was published by Groenteman & Co., the game was actively distributed and promoted. See the flier below, for example, by the distributor Perry & Co.

In these years just before the War, when Schada was published by Groenteman & Co., the game was actively distributed and promoted. See the flier below, for example, by the distributor Perry & Co.

The paper Het Vaderland of December 13, 1937 reports on a Schada demonstration, with Mr. Groenteman present in person. In his rules from 1939, Boogerd himself cites a game from the Rotterdam Individual Championship of 1938 and 1939.

With good publicity drummed up by Groenteman & Co., and a lot of attention from Chess players and Checkers players, the future for Schada looked promising. However, neither "the greatest measure of thought in the world" nor Groenteman & Co. itself survived long after World War II.

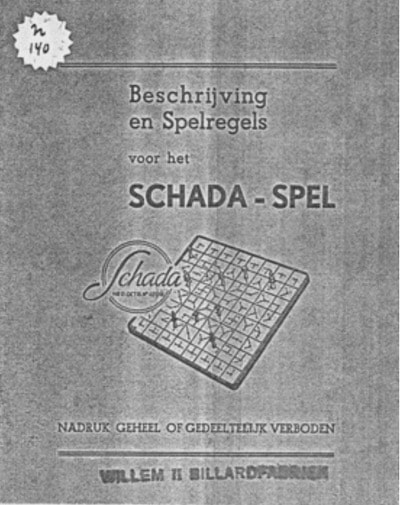

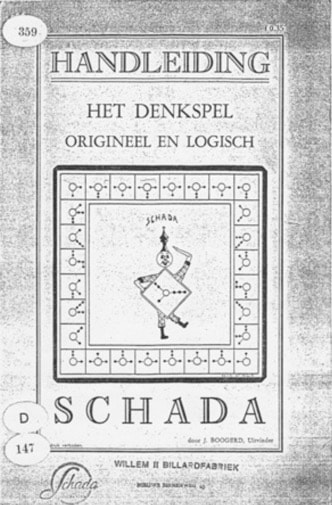

Shown below are two documents from 1939 giving the rules of Schada, from the collection of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in Den Haag. Boogerd’s "Handleiding" on the right, meaning rules, describes "an original and logical mindgame." This version was the basis for the Rules section below.

With good publicity drummed up by Groenteman & Co., and a lot of attention from Chess players and Checkers players, the future for Schada looked promising. However, neither "the greatest measure of thought in the world" nor Groenteman & Co. itself survived long after World War II.

Shown below are two documents from 1939 giving the rules of Schada, from the collection of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in Den Haag. Boogerd’s "Handleiding" on the right, meaning rules, describes "an original and logical mindgame." This version was the basis for the Rules section below.

As we have seen, Schada was developed probably in 1936, and then played and promoted in the Netherlands, perhaps primarily in Rotterdam, Boogerd's home town, from 1937 to 1939. However, World War II did not end the career of Schada immediately, as various versions were published during and even a little after the War.

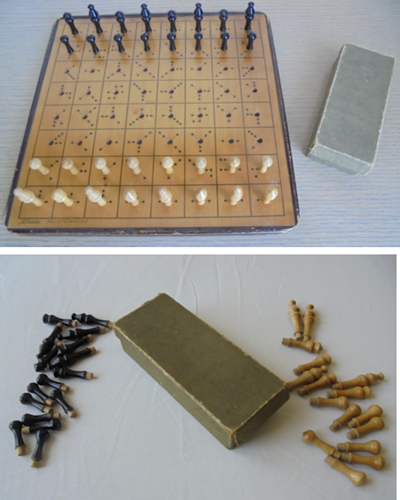

The image below shows a pre-War version of Schada. The board of this time is of thick wood, with rounded or sharp corners. The playing pieces may be metal, as in the De Tijd image in the header, or of wood, as shown below. In this wooden version, the pieces were usually stored in a small box with the name of the game on the lid.

The image below shows a pre-War version of Schada. The board of this time is of thick wood, with rounded or sharp corners. The playing pieces may be metal, as in the De Tijd image in the header, or of wood, as shown below. In this wooden version, the pieces were usually stored in a small box with the name of the game on the lid.

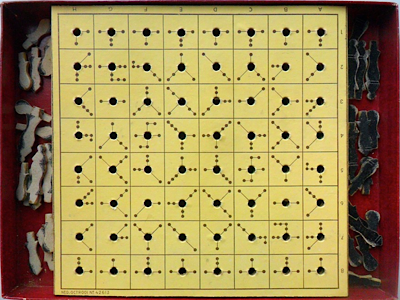

During the War a simplified cardboard version was published by Multicolor of Deventer, as shown below.

The markings on this board are clearly visible, and this image was the inspiration for the reconstructed board, in the Rules section, below.

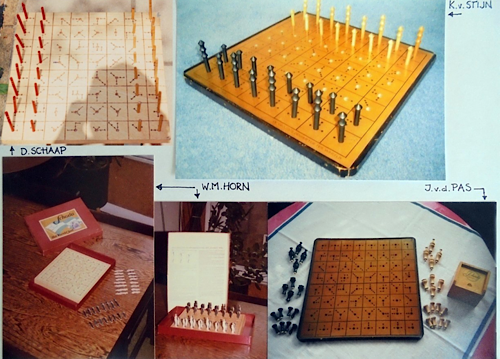

Other versions of board and pieces are known, as shown below, but information about dates of production or the publisher(s) does not exist.

Other versions of board and pieces are known, as shown below, but information about dates of production or the publisher(s) does not exist.

In 1991, Hans Hendrix wrote me to get information about Schada. I sent him the rules and some further information, but I did not hear back until 2020. For all these years, Mr. Hendrix had kept my letter, and after finding my mailing address he offered me his copy of the game for my collection. As it turned out, this game must be a Wartime version, as it bears the patent number 46.213, discussed above, and expected for this period. However, the pieces are stored in a cardboard box, not in one of wood, as shown below.

The date of circa 1941-1942 is substantiated by the use of less material for the board. The board Mr. Hendrix gave me is thinner than boards from before the War, as shown below.

In summary, my investigations of Schada describe yet another game in the long history of abstract gaming, which has been published and strongly promoted by its inventor. The wealth of published versions of the game, as well as the story of the patents and at least one tournament, demonstrate that Schada must have created a stir in the period around World War II. Sadly, like so many other abstract games Schada fell back into obscurity after a few short years. The De Tijd article of 1974 shows that even at that date the inventor was still hoping Schada would be republished. Perhaps the readers of this article will be inspired to try Schada, and re-evaluate it for the modern era.

Rules of Schada

by Kerry Handscomb

by Kerry Handscomb

The rules here are based on those in the rulebook by Jan Boogerd (1939, Rotterdam), which was obtained by Fred Horn from the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in Den Haag. However, the rules below are completely rewritten, rather than a translation, with diagrams and commentary, and hopefully some clarification.

Let us begin with the words of the game's designer, taken from the rulebook and translated by Fred Horn:

Let us begin with the words of the game's designer, taken from the rulebook and translated by Fred Horn:

"When looking at the Schada game board you will definitely wonder what these dots on the 64 spaces are for. But these dots, respected reader, represent something new in the sport of thinking. When you glance through the rules, it will be soon clear to you that these dots are very important. The aim of my invention was to make the value and the movement of the game-pieces dependent on the spaces, in contrast with existing board games. Thereby, a real way to measure thinking evolved, according to the powers of the players to win points in the games that they play. The chance of a draw or endless repetition is so small as to be practically zero. This way of measuring thought should seem especially original and logical and conducive to everybody. I have spent a long time practicing Schada, and the game is still becoming more and more difficult and complicated. I advise anyone who starts to play the game Schada not to look at it as easy, because that would lead to disappointment when playing against a more serious player. After a short while, it was clear to me that the problems to solve and the possibilities of play have no limit."

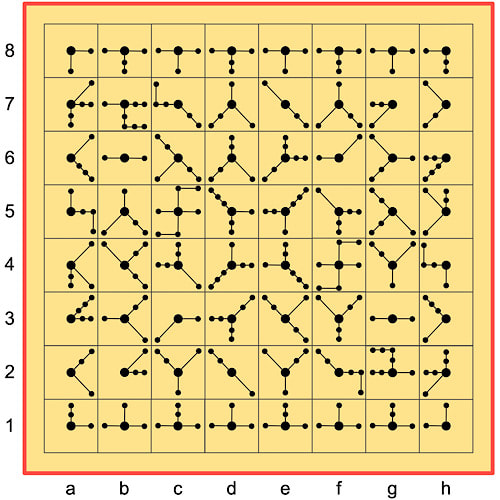

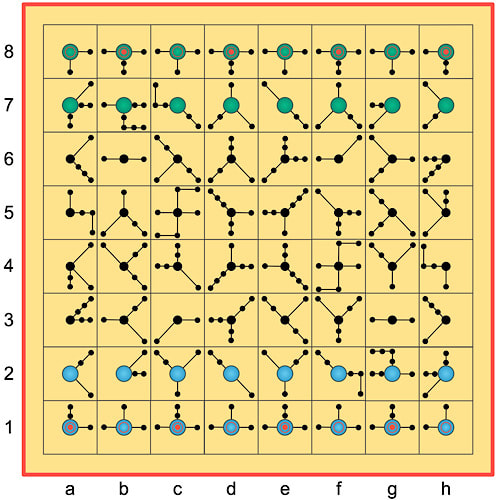

Schada is played on the board shown below, which is available as a PDF file here. Our reproduction of the board is close to the original, although there are minor cosmetic changes that hopefully make the design a little more logical—basically, the lengths of some of the lines are altered. The original pieces were peg-like, and fitted into the holes on the board, like a travel Chess set, and these holes are indicated by the larger circles in the centre of each square. The lines with the smaller circles on each square display the directions and numbers of squares that a piece can move that occupies that square. The lengths of the lines is irrelevant. Each dot on a line just means one square in that direction. You will see that the top half of the board is simply a 180 degree rotation of the bottom half of the board. Some of the squares (f2, f4, g2, and h4) specify that a piece must even change direction during its move.

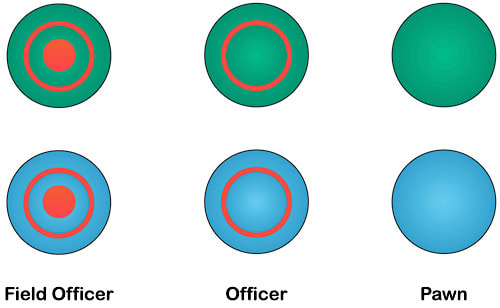

There are three kinds of pieces, Field Officers, Officers, and Pawns (respectively, Hoofd-Officier, Officier, and Pion in the original Dutch). The Field Officers and Officers are collectively referred to as high pieces. I have shown the pieces in blue and green, although the original pieces were shades of brown or white and black. The circular markings on the pieces are purely symbolic, but are meant to represent the kinds of designs used for actual Schada pieces.

One player takes blue pieces, the other takes the green. Each army consists of four Field Officers, four Officers, and eight Pawns. The starting position is shown below. The pieces must necessarily be compact so as not to obscure the movement indicators on the board.

A player's base line is the row of squares closest to him, which contain his high pieces. His goal line is the row furthest from him, containing his opponent's high pieces. Note that the Field Officers face enemy Officers, and vice versa.

The direction a piece can move and the number of squares it can move is indicated by the square it stands on. For example, a piece on d3 could move to d1, a3, or f5. As I mentioned above, a piece may have to change direction during its move. A piece on f2, for example, can move to d4, but also to h1. A piece must complete its full movement. For example, the piece on f2 cannot stop on g2 or h2 in its journey to h1. All squares along the way must be empty of both enemy and friendly pieces, except if the last square in a move is occupied by an enemy piece. In this case, the enemy piece is captured and removed from the game, and the moving piece takes its place. This is capture by replacement, common to Chess. The Field Officers have an exception in their movement rules: a Field Officer can pass over squares occupied by friendly pieces in the course of its move. No piece can ever land on a space occupied by a friendly piece, not even a Field Officer.

From the starting position, you can see that each of the eight Pawns can move, and the c2 and e2 Pawns have two movement options. The Field Officers on a1, c1, e1, and g1 can each move forward over the intervening Pawns to the third rank at the start of the game. Therefore, there are 14 possible moves from the opening position.

The object of the game is to move your high pieces into your goal line.

A high piece can shuffle left and right on your base line, perhaps to prevent an opponent's high piece from entering your base line. However, once a high piece has left its base line, it cannot return to it. On the other hand, once your high piece reaches its goal line, it can shuffle left and right on the goal line, perhaps to make way for one of its colleagues or block an enemy piece, but it cannot leave its goal line. The Pawns have no restrictions on movement in and of the base line and goal line. Their role is to defend and support the high pieces.

High pieces that have reached their goal line cannot be captured although they can still capture enemy pieces. Otherwise, any type of piece can capture any other type of enemy piece, without restriction. Capture is not compulsory.

The game ends as soon as all of a player's remaining high pieces (those that have not been captured) are in the goal line. The move that accomplishes this objective finishes the game immediately.

There are several other possible end-conditions for the game. As with games like Halma (see AG15 and AG18), pieces may get blocked and not be able to make further progress towards their goal. The game ends if a player has no high pieces outside the goal line that can move, because their movement is blocked. The original rules are vague on this point. However, my interpretation is that the blocking pieces have to be enemy pieces. Friendly pieces blocking a high piece do not trigger the end of the game.

The rules state also that the game ends, by repetition, when the identical board position occurs three times.

Lastly, if both players in consecutive turns shuffle high pieces back and forth within their base line or goal line, the game ends.

When the game ends, the players score to see who has won. A Field Officer in the goal line is worth 2 points; an Officer in the goal line is worth 1 point. The player with the higher score wins. Obviously, you do not want to end the game immediately if you have a lower score than your opponent!

If the scores of high pieces in the goal lines is tied, the player with the highest score of high pieces outside his goal line wins (Field Officers, 2; Officers, 1). In a normal game end, only one person, of course, will have high pieces outside his goal line, and this person will win. However, in the case of a game ended because of repetition, for example, both players may have high pieces outside their goal line.

If the players are still tied, calculate the values of all the high pieces outside their respective goal lines for each player in the following manner. Each row further from the base line counts 2/7 for the Field Officers and 1/7 for the Officers. If even this calculation is equal, the game is genuinely tied.

The rules to decide otherwise drawn games are complex, but I suspect that they are rarely needed. The designer of the game is rewarding firstly accomplishment of the objective of getting high pieces into the goal line, and secondarily the winning of "territory" by moving pieces at least towards the goal line.

The direction a piece can move and the number of squares it can move is indicated by the square it stands on. For example, a piece on d3 could move to d1, a3, or f5. As I mentioned above, a piece may have to change direction during its move. A piece on f2, for example, can move to d4, but also to h1. A piece must complete its full movement. For example, the piece on f2 cannot stop on g2 or h2 in its journey to h1. All squares along the way must be empty of both enemy and friendly pieces, except if the last square in a move is occupied by an enemy piece. In this case, the enemy piece is captured and removed from the game, and the moving piece takes its place. This is capture by replacement, common to Chess. The Field Officers have an exception in their movement rules: a Field Officer can pass over squares occupied by friendly pieces in the course of its move. No piece can ever land on a space occupied by a friendly piece, not even a Field Officer.

From the starting position, you can see that each of the eight Pawns can move, and the c2 and e2 Pawns have two movement options. The Field Officers on a1, c1, e1, and g1 can each move forward over the intervening Pawns to the third rank at the start of the game. Therefore, there are 14 possible moves from the opening position.

The object of the game is to move your high pieces into your goal line.

A high piece can shuffle left and right on your base line, perhaps to prevent an opponent's high piece from entering your base line. However, once a high piece has left its base line, it cannot return to it. On the other hand, once your high piece reaches its goal line, it can shuffle left and right on the goal line, perhaps to make way for one of its colleagues or block an enemy piece, but it cannot leave its goal line. The Pawns have no restrictions on movement in and of the base line and goal line. Their role is to defend and support the high pieces.

High pieces that have reached their goal line cannot be captured although they can still capture enemy pieces. Otherwise, any type of piece can capture any other type of enemy piece, without restriction. Capture is not compulsory.

The game ends as soon as all of a player's remaining high pieces (those that have not been captured) are in the goal line. The move that accomplishes this objective finishes the game immediately.

There are several other possible end-conditions for the game. As with games like Halma (see AG15 and AG18), pieces may get blocked and not be able to make further progress towards their goal. The game ends if a player has no high pieces outside the goal line that can move, because their movement is blocked. The original rules are vague on this point. However, my interpretation is that the blocking pieces have to be enemy pieces. Friendly pieces blocking a high piece do not trigger the end of the game.

The rules state also that the game ends, by repetition, when the identical board position occurs three times.

Lastly, if both players in consecutive turns shuffle high pieces back and forth within their base line or goal line, the game ends.

When the game ends, the players score to see who has won. A Field Officer in the goal line is worth 2 points; an Officer in the goal line is worth 1 point. The player with the higher score wins. Obviously, you do not want to end the game immediately if you have a lower score than your opponent!

If the scores of high pieces in the goal lines is tied, the player with the highest score of high pieces outside his goal line wins (Field Officers, 2; Officers, 1). In a normal game end, only one person, of course, will have high pieces outside his goal line, and this person will win. However, in the case of a game ended because of repetition, for example, both players may have high pieces outside their goal line.

If the players are still tied, calculate the values of all the high pieces outside their respective goal lines for each player in the following manner. Each row further from the base line counts 2/7 for the Field Officers and 1/7 for the Officers. If even this calculation is equal, the game is genuinely tied.

The rules to decide otherwise drawn games are complex, but I suspect that they are rarely needed. The designer of the game is rewarding firstly accomplishment of the objective of getting high pieces into the goal line, and secondarily the winning of "territory" by moving pieces at least towards the goal line.

Acknowledgement

- The 1939 rule booklet that was the basis for the description of Schada was sourced from the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in Den Haag (The Royal Library in The Hague).

- An earlier version of the investigation by Fred Horn was published in the quarterly magazine of the AGPI (Association for Games & Puzzles International), formerly known as the AGPC (Association of Games & Puzzle Collectors), in AGPC V.18 No. 2, Summer 2016. The updated version here is published with permission.

- The article for the AGPI quarterly magazine was the subject for a presentation for the Board Game Studies symposium at Spiele-Archiv Nuremberg on April 13-16, 2016.