As we become more mature our understanding of the world grows. We become wiser, more ethical and overall better human beings. There are however two disadvantages to becoming older. First our analytical power drops; second our memory deteriorates. And if that alone was not enough, modern Chess is filled with youngsters and computers, both known for their great tactical skills and memory of sharp opening variations. Chess is no longer the game it was, but there is solution to all of this—start playing Shatranj instead! The game is slower and more strategic, and you do not need to memorize long forced-move sequences. Just set up a Tabiyah and start to play!

Shatranj, or Chatrang, is the oldest known chess variant, with references and archeology dating back to Sixth Century Persia, and descriptions of the rules dating back to Arabic manuscripts from the Ninth Century. Because it is widely believed among chess historians that Arabic Shatranj only differed from Persian Chatrang in piece design and piece names, the game has a unique continuity of around 1500 years. No other chess variant has close to Shatranj's longevity—the modern Chinese XiangQi being closest, with its history dating from the Eleventh Century up to the present.

In this first part of the article, the main issue is to talk about the science of the game with reference to the strongest Arabic players. In the second part of the article, we will take a closer look at the rule changes in the European Middle ages. What consequences did these rule changes have for the game? My special thanks go to H.G. Muller for adjusting his Shatranj Tablebase to rules of the European Middle Ages, and for solving the most interesting endings. The final part of this article will also deal with Shatranj and computers, and present my own games against different Shatranj engines.

The second and third parts will be presented in future issues of Abstract Games. The reference list for the whole series is given at the end of this first part, although direct citations are sometimes informal or even omitted.

Shatranj pieces

The Arabic Shatranj game probably did not differ from the original Persian Chatrang that the conquering Arabs found in Persia. However, the piece design became non-figurative due to the aniconism of Islamic art, which avoids the images of sentient beings. Islamic aniconism stems in part from the prohibition of idolatry, and in part from the belief that the creation of living forms is God's prerogative. However as pointed out by Ferlito (1994) the non-figurative piece form seemed more like a functional fashion than a religious ban. The abstract pieces were more durable, and hence popular even later in Europe.

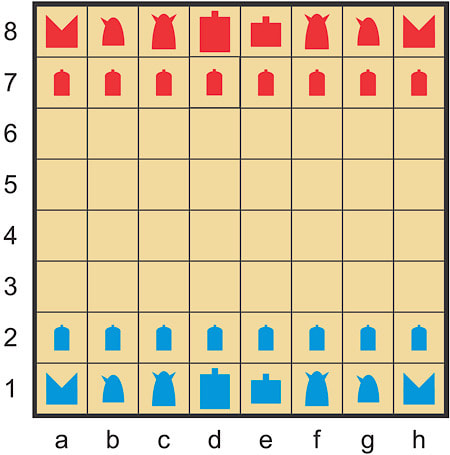

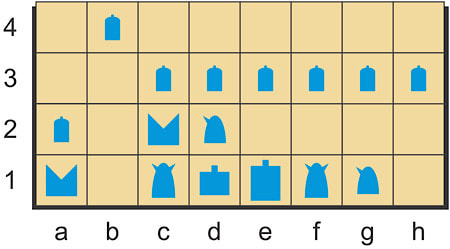

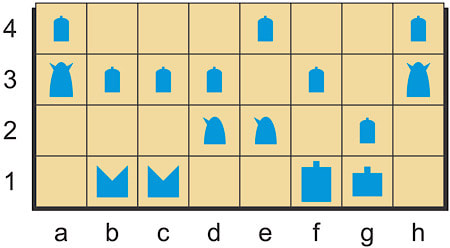

The design we will use for the diagrams throughout our discussion of Shatranj is shown below. It follows fairly closely the design of a traditional Arabic Shatranj set, although somewhat more stylized. The colours of each side were typically blue or black and red. It did not matter which colour moved first. In our presentation, Blue will have the first move.

Shatranj, or Chatrang, is the oldest known chess variant, with references and archeology dating back to Sixth Century Persia, and descriptions of the rules dating back to Arabic manuscripts from the Ninth Century. Because it is widely believed among chess historians that Arabic Shatranj only differed from Persian Chatrang in piece design and piece names, the game has a unique continuity of around 1500 years. No other chess variant has close to Shatranj's longevity—the modern Chinese XiangQi being closest, with its history dating from the Eleventh Century up to the present.

In this first part of the article, the main issue is to talk about the science of the game with reference to the strongest Arabic players. In the second part of the article, we will take a closer look at the rule changes in the European Middle ages. What consequences did these rule changes have for the game? My special thanks go to H.G. Muller for adjusting his Shatranj Tablebase to rules of the European Middle Ages, and for solving the most interesting endings. The final part of this article will also deal with Shatranj and computers, and present my own games against different Shatranj engines.

The second and third parts will be presented in future issues of Abstract Games. The reference list for the whole series is given at the end of this first part, although direct citations are sometimes informal or even omitted.

Shatranj pieces

The Arabic Shatranj game probably did not differ from the original Persian Chatrang that the conquering Arabs found in Persia. However, the piece design became non-figurative due to the aniconism of Islamic art, which avoids the images of sentient beings. Islamic aniconism stems in part from the prohibition of idolatry, and in part from the belief that the creation of living forms is God's prerogative. However as pointed out by Ferlito (1994) the non-figurative piece form seemed more like a functional fashion than a religious ban. The abstract pieces were more durable, and hence popular even later in Europe.

The design we will use for the diagrams throughout our discussion of Shatranj is shown below. It follows fairly closely the design of a traditional Arabic Shatranj set, although somewhat more stylized. The colours of each side were typically blue or black and red. It did not matter which colour moved first. In our presentation, Blue will have the first move.

Rules

The rules of Shatranj are the same as the standard Western game, with the same setup, except for the following:

The Persian heritage

Ever since the beginning of chess, Persia played the leading role in the development of the game. After the Islamic conquest, in the period 633-651 CE, the leading Shatranj masters continued to come from the original Persian areas of what now became the Islamic Sasanian Empire—including the city of Baghdad, which was earlier the Persian capital and subsequently the residence of the Islamic Sultans. Below, we will refer to "Islamic players," meaning that they resided in the Islamic Empire.

Opening and middle game theory

The Islamic players used Tabiyas—opening piece setups that varied from 8 to 22 moves, and which were more or less independent of the opponent’s moves. In the Tenth Century as-Suli and al-Lajlaj argued for the use of shorter Tabiyas and even abandoning Tabiyas altogether. Al-Lajlaj even published opening analyses stretching up to 20 moves. Modern players, of course, do not have to use a traditional Tabiya.

The skill level of the players seems to have been comparatively high, and we hear about Arabic players in the late Middle Ages playing up to 8-10 games blindfolded (Wilson, 1981; Hearst & Knott, 2009), with Sa’id bin Jubair (665-714 CE) being the first known blindfold chess player ever. In European terms, his achievements are parallel to those of Louis Paulsen and Paul Morphy of the mid-Nineteenth Century.

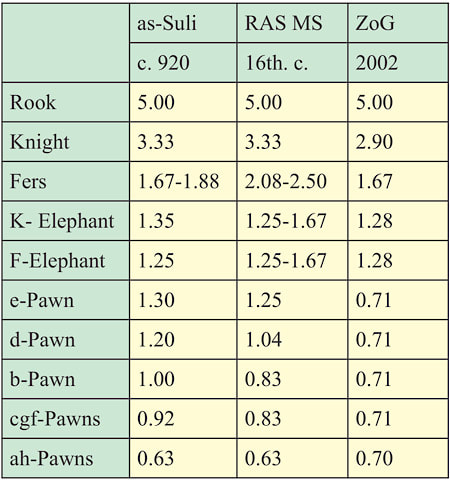

The Islamic players also created piece value tables and below we can see a comparison of piece-values from as-Suli, a Sixteenth Century Persian manuscript, and the modern Zillions of Games engine.

The rules of Shatranj are the same as the standard Western game, with the same setup, except for the following:

- The game is won by checkmate, by capturing all opposing pieces except the enemy King, or by stalemate.

- The Bishop is replaced by the Elephant, which jumps two squares diagonally. This piece is still present in XiangQi.

- The Queen is replaced by the Fers (Advisor) that moves one square diagonally. This piece is still to be found in both Thai Makruk and XiangQi.

- The Pawn moves only one square, even on its first move. There is no en passant.

- When the Pawn reaches the last row, it automatically becomes a Fers. Multiple Ferses are allowed.

- There is no castling.

- Instead of the 50 move draw rule, there is a 70 move draw rule (Hooper and Whyld, 1992). In other words, a player can claim a draw if each player has made 70 moves, during which no capture has been made and no Pawn has been moved.

The Persian heritage

Ever since the beginning of chess, Persia played the leading role in the development of the game. After the Islamic conquest, in the period 633-651 CE, the leading Shatranj masters continued to come from the original Persian areas of what now became the Islamic Sasanian Empire—including the city of Baghdad, which was earlier the Persian capital and subsequently the residence of the Islamic Sultans. Below, we will refer to "Islamic players," meaning that they resided in the Islamic Empire.

Opening and middle game theory

The Islamic players used Tabiyas—opening piece setups that varied from 8 to 22 moves, and which were more or less independent of the opponent’s moves. In the Tenth Century as-Suli and al-Lajlaj argued for the use of shorter Tabiyas and even abandoning Tabiyas altogether. Al-Lajlaj even published opening analyses stretching up to 20 moves. Modern players, of course, do not have to use a traditional Tabiya.

The skill level of the players seems to have been comparatively high, and we hear about Arabic players in the late Middle Ages playing up to 8-10 games blindfolded (Wilson, 1981; Hearst & Knott, 2009), with Sa’id bin Jubair (665-714 CE) being the first known blindfold chess player ever. In European terms, his achievements are parallel to those of Louis Paulsen and Paul Morphy of the mid-Nineteenth Century.

The Islamic players also created piece value tables and below we can see a comparison of piece-values from as-Suli, a Sixteenth Century Persian manuscript, and the modern Zillions of Games engine.

The Islamic players, starting with Rabrab and Abu'n Na'ān, and continuing with as-Suli, had a high opinion of the central Pawns, advocating that two central Pawns, or even two random Pawns, were stronger than a single Fers. As-Suli even tells us that some of his contemporaries thought two central Pawns were stronger than a Knight. The Islamic players were also afraid of using Knights and Rooks in the opening due to the risk of these strong pieces being chased back by weaker pieces. This led them to make many slow Pawn and Elephant moves. The following game is taken from Hesse (2007), and is played between the grand master as-Suli and the reigning Sultan al-Muqtadir.

Yahya as-Suli vs. al-Muqtadir

Baghdad , circa 920.

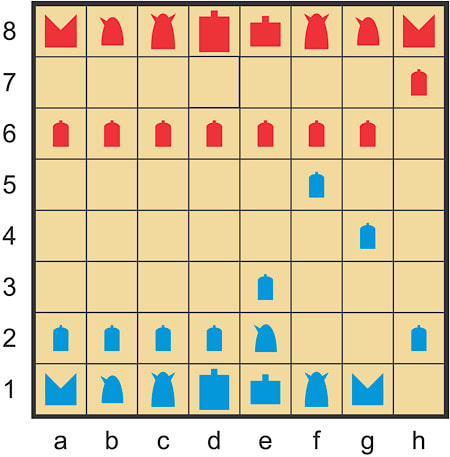

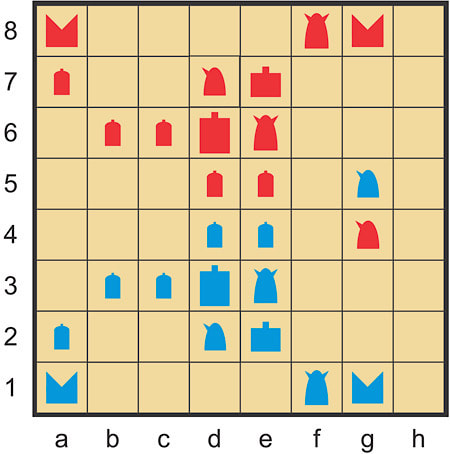

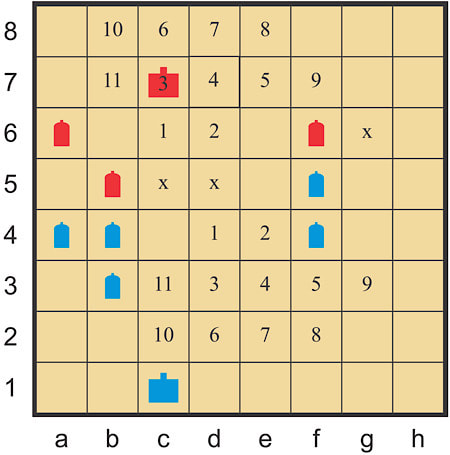

1.g3 g6, 2.g4!? (A curious move, especially given the fact that none of the as-Suli or al-Lajlaj Tabiyahs place the g-Pawn on its second square. It reminds us of the eccentric Steinitz move in the French defence: 1.e4 e6, 2.e5!?) 2…f6, 3.e3 e6, 4.Ne2 d6, 5.Rg1 c6, 6.f3 b6, 7.f4 a6 (What al-Muqtadir is doing is placing the Pawns on the sixth row, according to the Sayayala Tabiyah, where seven Pawns move one square each. Our champion does not do much different, and as we soon will see, surprisingly, after nine moves on each side only one Knight is out and this Knight is placed on e2.) 8.f5!? (Diagram 2)

Yahya as-Suli vs. al-Muqtadir

Baghdad , circa 920.

1.g3 g6, 2.g4!? (A curious move, especially given the fact that none of the as-Suli or al-Lajlaj Tabiyahs place the g-Pawn on its second square. It reminds us of the eccentric Steinitz move in the French defence: 1.e4 e6, 2.e5!?) 2…f6, 3.e3 e6, 4.Ne2 d6, 5.Rg1 c6, 6.f3 b6, 7.f4 a6 (What al-Muqtadir is doing is placing the Pawns on the sixth row, according to the Sayayala Tabiyah, where seven Pawns move one square each. Our champion does not do much different, and as we soon will see, surprisingly, after nine moves on each side only one Knight is out and this Knight is placed on e2.) 8.f5!? (Diagram 2)

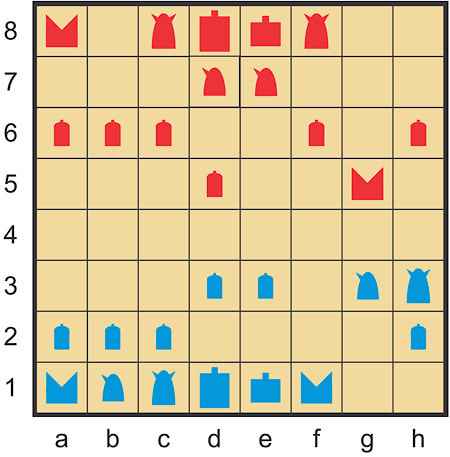

8…exf5? (Red should have stayed flexible either by playing 8…Ra7, with the idea of …Rg7 and …gxf5, or by simply developing the Knight to d7.) 9.gxf5 gxf5?! (Red has created an ugly double Pawn. Better was 8…Ne7.) 10.Eh3 Ne7, 11.Rf1 Rg8, 12.Ng3 Rg5 13.Exf5 (Blue gets a very strong outpost for his Elephant, where it controls the important d7-square.) 13…h6, 14.Eh3? (There was no reason to retreat the Elephant and lose control over the d-square.) 14…Nd7, 15.d3 d5 (Diagram 3--As-Suli as Blue has gained a slight advantage over the Sultan thanks to Red’s weak f6-Pawn. But how shall Blue proceed?)

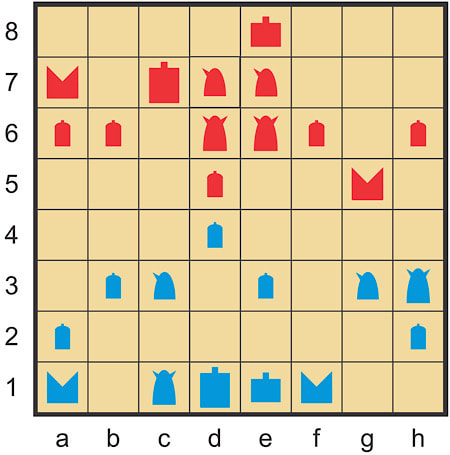

16.c3?! (Blue initiates static, Pawn-oriented play, not grasping the dynamics of the positions. Placing the Knight on c3 would have been better.) 16…Fc7?! (Red plays to proceed with the Fers into the centre, when the path is ready. However he misses good counter chances after 16…Ne5, 17.Rf2 Ng4 and Blue must already try to solve some problems.) 17.b3? (This however is definitely bad. Blue should have hindered the Knight coming to the e5 square with 17.d4.) 17…Ra7? (Here the Sultan misses the opportunity to seize the initiative after 17...Ne5! 18.Rxf6 Rg3.) 18.c4?! (Again those static Pawn moves!) 18…Ed6?! (Here again Red ought to play the Knight to e5 with the idea of Ng4, threatening the h2-Pawn.) 19.Nc3 Ee6, 20.cxd5 cxd5, 21.d4 (Diagram 4).

21....Ef8? (There was no need to retreat the Elephant. Zillions of Games proposes 21....h5, with the idea of countering 22.e4 with 22....h4!) 22.Rf2 (As-Suli is still better, and after some further grave mistakes, the Sultan lost after 35 moves.)

Here it must be pointed out that prioritizing Pawn moves versus Knight moves is something that dominated the Western Chess world into the middle of the Nineteenth Century, with for instance almost exclusively closed lines in both Sicilian and French defences. 1.e4 c5, 2.Nf3 with the 3.d4 advance started slowly in the 1830's with Alexander Mc Donnel, whereas 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 was first initiated by Louis Paulsen in the 1860's, soon to be followed by Wilhelm Steinitz.

There was also a tendency to discriminate between the different Pawns and Elephants, which the Zillion of Games engine finds faulty. Commenting on the RAS manuscript, Murray (1913) states that the manuscript overestimates the values of the Fers and Elephants. If we take the middle values (Fers 2.29 and Elephant 1.46), Murray's claim makes sense for the Fers. However, this is true because the Fers is valued too highly compared to the Rook and Knight. The problem could have been solved by reducing the values of Pawns, and keeping the values of other pieces constant.

Both as-Suli and later al-Lajlaj argued for oppositional play, which meant blocking Pawn advances by simply mirroring the opponent’s moves. The following game is taken from Gralla (2010).

Yahya as-Suli vs. Sa’-id al-Lajlaj

Baghdad circa 920.

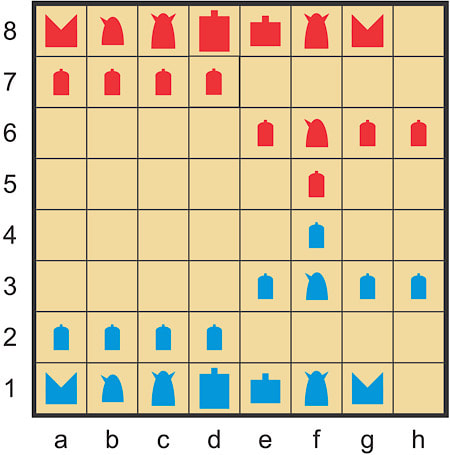

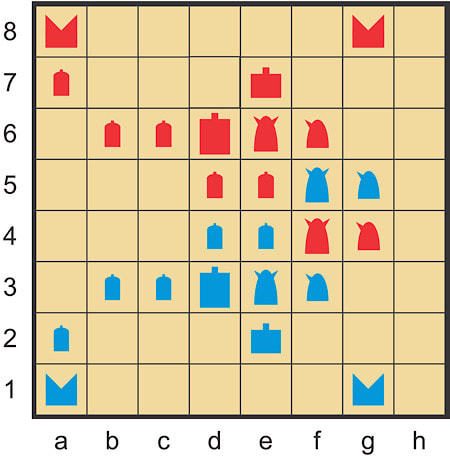

1.f3 f6, 2.f4 f5, 3.Nf3 Nf6, 4.g3 g6, 5.Rg1 Rg8, 6.h3 h6, 7.e3 e6 (Diagram 5).

Here it must be pointed out that prioritizing Pawn moves versus Knight moves is something that dominated the Western Chess world into the middle of the Nineteenth Century, with for instance almost exclusively closed lines in both Sicilian and French defences. 1.e4 c5, 2.Nf3 with the 3.d4 advance started slowly in the 1830's with Alexander Mc Donnel, whereas 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 was first initiated by Louis Paulsen in the 1860's, soon to be followed by Wilhelm Steinitz.

There was also a tendency to discriminate between the different Pawns and Elephants, which the Zillion of Games engine finds faulty. Commenting on the RAS manuscript, Murray (1913) states that the manuscript overestimates the values of the Fers and Elephants. If we take the middle values (Fers 2.29 and Elephant 1.46), Murray's claim makes sense for the Fers. However, this is true because the Fers is valued too highly compared to the Rook and Knight. The problem could have been solved by reducing the values of Pawns, and keeping the values of other pieces constant.

Both as-Suli and later al-Lajlaj argued for oppositional play, which meant blocking Pawn advances by simply mirroring the opponent’s moves. The following game is taken from Gralla (2010).

Yahya as-Suli vs. Sa’-id al-Lajlaj

Baghdad circa 920.

1.f3 f6, 2.f4 f5, 3.Nf3 Nf6, 4.g3 g6, 5.Rg1 Rg8, 6.h3 h6, 7.e3 e6 (Diagram 5).

8.g4. (We witness a broken Mujannah Tabiya, which is not completed.) 8…fxg4, 9.hxg4 g5 (An obligatory move, because Blue’s 10.g5 hxg5, 11.fxg5 seemed somewhat annoying to Red.) 10.fxg5 hxg5, 11.d3 (As-Suli is setting up a central Pawn structure, aiming for the c-Elephant to keep the pressure on Red’s g5-Pawn.) 11…d6, 12.e4 e5, 13.Ee3 Ee6. (Al-Lajlaj continues to mirror his more meritorious opponent. Since the piece movement in Shatranj is far slower than in most other chess variants, this strategy can be used to a far more frequent extent.) 14.Nxg5 Ke7?! (There was no reason to move the King, and 14… Exg4 was stronger.) 15.c3 (As-Suli here chooses to play with the Pawns in order to get a central breakthrough. More dynamic was 15.Nc3, followed by a transfer to the King’s wing, where Blue could develop an offensive.) 15…Nxg4, 16.Ke2 c6, 17.d4 d5 (Blue is himself threatening the d4-d5 advance.) 18.b3 b6, 19. Nd2 Nd7, 20.Fc2! (Activating the Fers is an important part of the game. Arab masters were therefore careful to make way for it. Moreover, this knowledge was rarely implemented in medieval Europe, where the players neglected the Fers’ role completely. Even worse was the view of the Europeans on the Elephant, where it was seen as a useless and suspicious piece that from time to time forked two stronger pieces.) 20…Fc7, 21.Fd3 Fd6 (Diagram 6).

(The game shows typical Fers placement in the Shatranj middle game. In the first part of the Twelfth Century, the Spanish-Jewish player Ezra introduced the d1-d3 / d8-d6 Fers jump—a rule that became accepted throughout the European continent.) 22.Ndf3 (The Knight ensures that the d4-Pawn will not hang after the future c4 advance.) 22…Ndf6, 23.Eh3 Eh6, 24.Ef5 Ef4 (Diagram 7).

25.Rac1! a6? (Red wastes a move. The positions would still be balanced after the more active 25. ... Rh8.) 26.c4! (A strong advance, and now al-Lajlaj must play precisely to stay away from trouble.) 26….Rac8? (Now the student gets into trouble. Necessary was 26… dxc4, 27.bxc4 c5, and if Blue advances with 28.d5, Red has a solid position after 28….Ec8.) 27.c5! bxc5, 28.Exc5? (A serious tactical error. As-Suli should have first driven the Fers from d6 with 28.dxe5 Nxe5, 29.Exc5 Ke8, 30.Ne6 with an advantage according to Zillions of Games.) 28….Ke8?? (Gives away the Elephant for free. With 28….Fxc5, 29.dxe5!—29.Rxc5 was far weaker—and then 29….Nxe4, 30.Fxe4 dxe4, 31.Nxe4 Fb4, Red is still fighting, with a small disadvantage, according to Zillions of Games.) 29.dxe5 Nxe5, 30.Nxe6 Rxg1, 31.Rxg1 Nxf3, 32.Kxf3 (Diagram 8--Red is lost after, for instance, 32…dxe4, 33.Fxe4 Ed2, 34.Rg7.)

Tabiyah development up to the sixteenth century

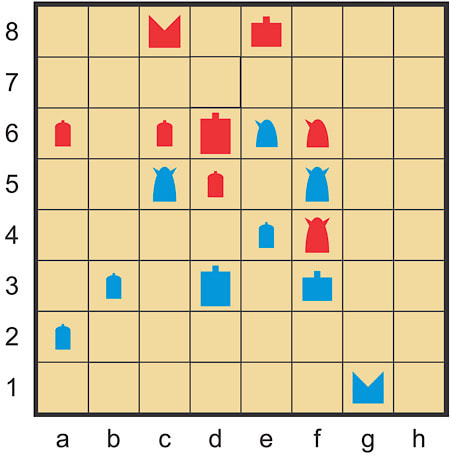

Did the Tabiya setups change from the Ninth to Sixteenth Century? It is difficult to make clear statements based on a total of only 50 known Tabiyas. However there are some obvious trends. First of all the Tabiyas continued to be long, despite as-Suli’s and al Lajlaj’s preference for shorter setups. Also, both the Islamic and European players preferred to move Pawns and neglected Knight development. The only big shift was the King placement. Whereas the King stayed at home in the classical times, starting from as far back as the fifteenth century, both Islamic and European players started to put the King on Elephant or Knight squares. Here are two examples, a classical Arabic Tabiya from the Tenth Century and a Turkish Tabiya from 1501.

Did the Tabiya setups change from the Ninth to Sixteenth Century? It is difficult to make clear statements based on a total of only 50 known Tabiyas. However there are some obvious trends. First of all the Tabiyas continued to be long, despite as-Suli’s and al Lajlaj’s preference for shorter setups. Also, both the Islamic and European players preferred to move Pawns and neglected Knight development. The only big shift was the King placement. Whereas the King stayed at home in the classical times, starting from as far back as the fifteenth century, both Islamic and European players started to put the King on Elephant or Knight squares. Here are two examples, a classical Arabic Tabiya from the Tenth Century and a Turkish Tabiya from 1501.

Although modern castling did not appear in Italy before the middle of the Sixteenth Century, the Kraków MS (1422) gives a combined King and Fers jump to g1 and f1, identical with the King and Fers position from the Turkish Gaharibana Maliha Tabiyah.

Endgame theory

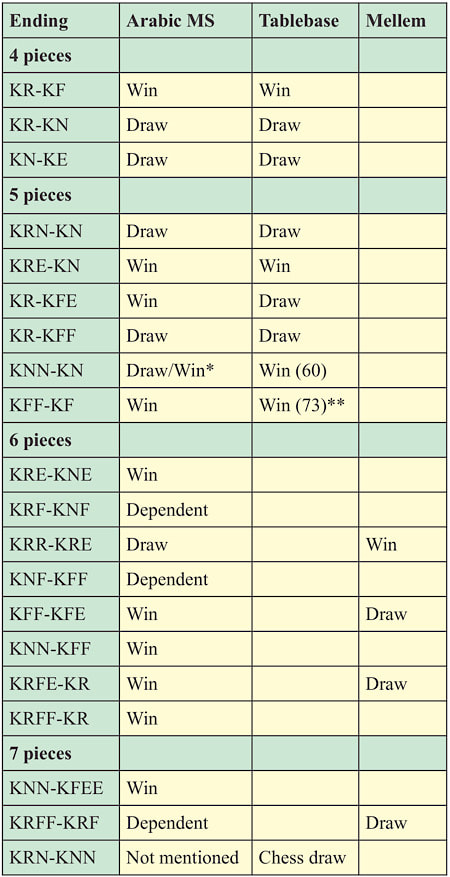

The most basic endgame understanding seemed relatively well developed among the Islamic players. However, as Murray (1913) points out, the statements about concrete endings were made with reference to well known masters, without giving any analysis. So for instance KNN-KN was a draw according to al-Adli but a win according to as-Suli. This five-piece endgame was solved by H.G. Muller's Five-Piece Tablebase and proved as-Suli right in claiming it was a win. The longest variation was 60 moves long, within the 70 move limit. This shows quite impressive insight as the endgame is difficult for a human player.

Endgame theory

The most basic endgame understanding seemed relatively well developed among the Islamic players. However, as Murray (1913) points out, the statements about concrete endings were made with reference to well known masters, without giving any analysis. So for instance KNN-KN was a draw according to al-Adli but a win according to as-Suli. This five-piece endgame was solved by H.G. Muller's Five-Piece Tablebase and proved as-Suli right in claiming it was a win. The longest variation was 60 moves long, within the 70 move limit. This shows quite impressive insight as the endgame is difficult for a human player.

* The KNN-KN ending was drawn according to al-Adli, but a win according to as-Suli.

** Some extreme KFF-KF positions exceed the 70-move limit and are hence drawn.

** Some extreme KFF-KF positions exceed the 70-move limit and are hence drawn.

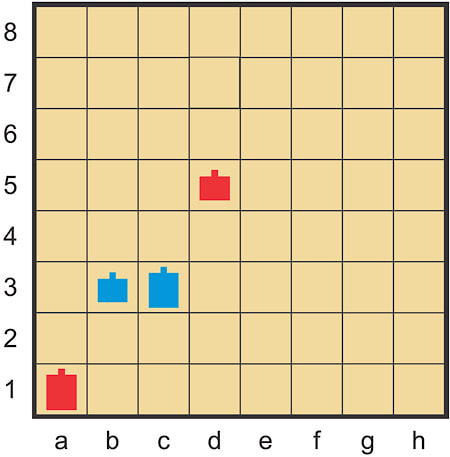

When in the beginning of the Tenth Century the Grand Master Yahya as-Suli constructed as-Suli's diamond it took more than 1000 years before the Soviet Grand Master and endgame expert Juri Averbach solved it.

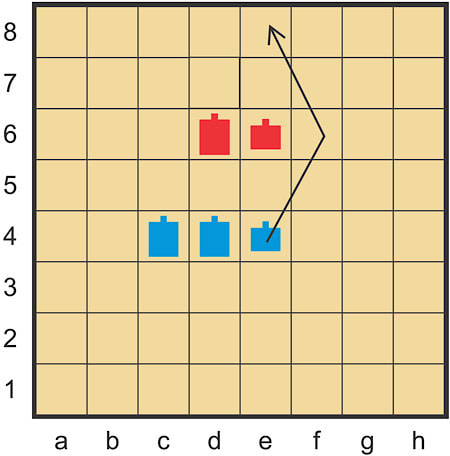

We will not give the solution to as-Suli's Diamond here, but the interested reader may research it! Let us now turn the tables—1000 years earlier, would as-Suli be able to solve the following Pawn endgame, created in the 1920's by the Soviet Chess composer and five-fold Moscow champion Nikolai Grigoriev?

This endgame is practically impossible to solve without the knowledge of corresponding squares theory. For instance Fritz 11 did not solve it, whereas the new Stockfish 10 did.

When we know the corresponding squares, we know how to win, starting with 1.Kd1 and following up with moves that prohibit Red from going to the same square number Blue moves to. In the end, we see that Red must let Blue break through on the right side. Blue promotes both his f-Pawns ,whereas Red promotes the sole b-Pawn. In the actual position, this gives an easy win in Chess, and normally in Shatranj two Ferses beat one Fers if at least one of them is concordant with the opposing Fers. Here, however, both Blue’s Ferses promote on a black square (on a Chess board), whereas Red gets the white b1 Fers.

But do not despair! In as-Suli’s time, the promoter had the option to change the square colour of a newly promoted Fers (Murray 1913). There is no detailed description of how this actually was fulfilled, but it would be natural to assume that after promoting on f8 Blue was allowed to make a special Fers move on the very next move, for example, Ff8-e8! The simplest win would include a colour change of both Ferses so they would both match the light b1-Fers. However, then Red could postpone his own promotion and go black himself, which in turn would secure him a draw. Hence, the two-coloured promotion solution secures the win for Blue.

In my practise, the KFF-KF endgame has occurred many times. Winning this endgame requires knowledge of a rather counter-intuitive plan—a King march around the enemy King leading to zugzwang. The longest KFF-KF win exceeds the 70 move limit rule by 3 moves. However, this is due to the first phase of the ending, where the stronger side uses time to defend the Ferses from the opponent’s King and Fers.

But do not despair! In as-Suli’s time, the promoter had the option to change the square colour of a newly promoted Fers (Murray 1913). There is no detailed description of how this actually was fulfilled, but it would be natural to assume that after promoting on f8 Blue was allowed to make a special Fers move on the very next move, for example, Ff8-e8! The simplest win would include a colour change of both Ferses so they would both match the light b1-Fers. However, then Red could postpone his own promotion and go black himself, which in turn would secure him a draw. Hence, the two-coloured promotion solution secures the win for Blue.

In my practise, the KFF-KF endgame has occurred many times. Winning this endgame requires knowledge of a rather counter-intuitive plan—a King march around the enemy King leading to zugzwang. The longest KFF-KF win exceeds the 70 move limit rule by 3 moves. However, this is due to the first phase of the ending, where the stronger side uses time to defend the Ferses from the opponent’s King and Fers.

We must also add that by the Twelfth Century, several locations in the Islamic world practised promotion to a King-moving piece instead of to a normal Fers. This rule change favoured the promoting side considerably, as the King-mover seems slightly stronger than the Knight, with a value of 3.40 given by Zillion of Games. In our Grigoriev position, the King and two King-moving pieces would easily win against the King and single King-mover.

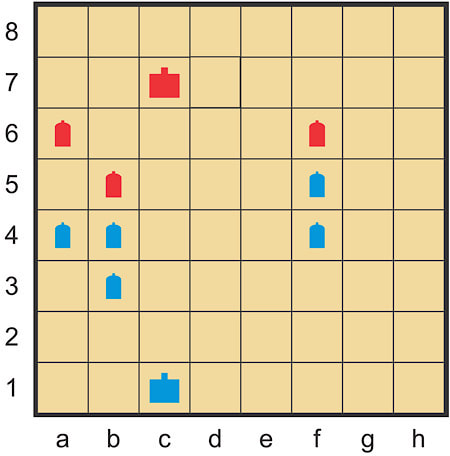

Another endgame that occurs often is KRFE-KR. The Arabic MS claims this endgame to be a win, no matter if the Fers and Elephant are connected. Still, we know of a story where the Grand Master Rabrab played this endgame against a weaker opponent, trying to win it for almost one day before giving up in disgust.

Unfortunately we still do not have six-piece Tablebases for Shatranj, but my practise against both myself and the Zillions of Games engine leads me to believe that the weak side is able to hold the strong side to a draw.

Literature list

All sources listed below were used as background material for this article, although direct citations in the text are informal or sometimes omitted.

Another endgame that occurs often is KRFE-KR. The Arabic MS claims this endgame to be a win, no matter if the Fers and Elephant are connected. Still, we know of a story where the Grand Master Rabrab played this endgame against a weaker opponent, trying to win it for almost one day before giving up in disgust.

Unfortunately we still do not have six-piece Tablebases for Shatranj, but my practise against both myself and the Zillions of Games engine leads me to believe that the weak side is able to hold the strong side to a draw.

Literature list

All sources listed below were used as background material for this article, although direct citations in the text are informal or sometimes omitted.

- Benary, Walter (1910). Zur Geschichte des Matsieges. In Deutsche Schachblätter. Coburg.

- Bubczyk, Robert (2009). Gry na szachownicy. Lublin.

- ChessCoach (2015). Philidor's Pawn Phalanx Strategy in a Game of Shatranj. Youtube (Retrieved May 4, 2020).

- Ferlito, Gianferlice (1994). "Old Islamic Chessmen." München. (Retrieved May 4, 2020).

- FinalGen – Endgame tablebase generator [Broken link].

- Golombek, Harry (1976). A History of Chess. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Gralla, René (2010). "Oldest chess game recorded." (Retrieved May 4, 2020).

- Hearst, Eliot S. & Knott, John (2009). Blindfold Chess — History, Champions, Psychology, Records. McFarland, USA.

- Hesse, Christian (2007). Expeditionen in die Schachwelt. Nettetal: Chessgate, Germany.

- Hooper, David & Whyld, Kenneth (1984). The Oxford Companion to Chess. Oxford.

- Kluge-Pinsker, Antje (1994). "Brettspiele, isnbesondere 'tabuale' und 'schacchis' im Alltag der Gesellschaft des 11. und 12. Jahrhundert." Homo Ludens, 4, pp. 69-79. München.

- Kohtz, Johannes (1910). "Von Ur-Schach." Desutsches Wochensschach. Potsdam.

- Kohtz, Johannes (1916). Kurtze Geschichte des Schachspiels. Dresden.

- Logistic Regression calculator. (Retrieved May 4, 2020)

- Müller, H. G. Shatranj 5-man tablebase.

- Murray, H. J. R. (1913). A History of Chess. Oxford. (Retrieved May 4, 2020)

- Murray, H J R (1911). Über die Erfindung des Schachspiels und die Geschichte de Beraubnungssieges. Postdam.

- Nalimov Endgame Tablebases. (Retrieved May 4, 2020)

- Pickthall, Marmaduke (1930). Quran. Cambridge. (Retrieved May 4, 2020)

- Regan, Kenneth W., Macieja, Bartolomiej, & Haworth, Guy McC. (2011). "Understanding Distributions of Chess Performances." Warszawa. (Retrieved May 4, 2020)

- Sadler, Matthew & Regan, Natasha (2019). Game Changer: Alpha Zero's Groundbreaking Chess Strategies and Promise of AI. New in Chess..

- Soltis, Andrew (2014). Soviet Chess 1917-1991. McFarland Publishing, England.

- Watson, John (1998). Secrets of Modern Chess Strategy. Gambit Publications, London.

- Wilson, Fred (1981). A Picture History of Chess. Dover Publications, New York.

Header image: Illustration from a Persian manuscript "A Treatise on Chess," Fourteenth Century.

Nikolas's comments that Shatranj is slower and more strategic than orthodox Chess echoes R. Wyne Schmittberger in New Rules for Classic Games (1992, John Wiley & Sons). Schmittberger notes that Shatranj is the ancestor of Chess, and goes on to comment,

But does evolution always go in the right direction? Shatranj has less powerful pieces than modern chess, but it also has great subtlety, depth, and charm, as well as elements of positional play that are absent in modern chess. It will remind chess players of the most challenging endgame they have ever encountered, and I recommend it highly.

The beauty of Shatranj, when compared with other more exotic chess variants, is that all you need to start playing is a regular Chess set. ~ Ed.