Game review

More often than not, the physical representation of an abstract game (that is, its components) is an afterthought, something that arises for aesthetics or usability purposes. Few game ideas start with the components as the central focus of the design, but while I cannot vouch that was the case with Carnac, one is hard pressed to think (when playing it) how this game came to be if not by starting from its pieces.

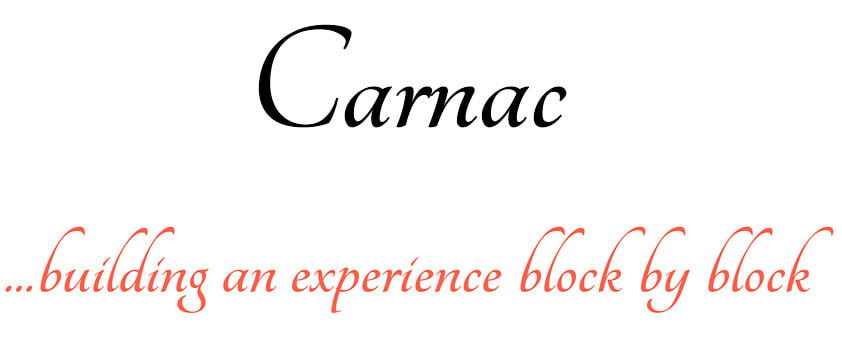

Carnac was designed by Emiliano “Wentu” Venturini and published by HUCH! in 2014. The game comes with a double-sided board and 28 equal pieces called megaliths that fit nicely in the well-thought-out and totally functional plastic insert. In one side of the board, you will find a small board (8x5 squares) and a medium board (10x7 squares) surrounding the smaller one; in the other, a large board with 126 squares (a 14x9 grid). The pieces, which are shared by both players, are dicubes patterned with their colours/symbols. Despite their small size (approximately 1x2x1 inches), they have a hefty weight to them and are a pleasure to handle (Figure 1). Each player’s sides are easily told apart not only by their colours, but their symbols which convey the thin veneer of theme (of building megalithic structures).

Carnac was designed by Emiliano “Wentu” Venturini and published by HUCH! in 2014. The game comes with a double-sided board and 28 equal pieces called megaliths that fit nicely in the well-thought-out and totally functional plastic insert. In one side of the board, you will find a small board (8x5 squares) and a medium board (10x7 squares) surrounding the smaller one; in the other, a large board with 126 squares (a 14x9 grid). The pieces, which are shared by both players, are dicubes patterned with their colours/symbols. Despite their small size (approximately 1x2x1 inches), they have a hefty weight to them and are a pleasure to handle (Figure 1). Each player’s sides are easily told apart not only by their colours, but their symbols which convey the thin veneer of theme (of building megalithic structures).

At the beginning of the game, players choose a board size and place the pieces within reach of both of them. On a given player’s turn (from now on, called the active player), they lay one of the pieces upright in the board. Now, the other player (here called the passive player) gets to decide A) to tilt that piece or B) leave it as is. In the former case, turn passes to the passive player; whereas in the latter case, the active player gets another turn (which always starts with a piece being placed upright). Tilting is done by laying the piece down in two neighbouring orthogonal empty spaces, leaving the original occupied space empty. If the piece is placed in a way that it cannot be tilted, turn just passes to the passive player. Players keep doing that until the common stockpile is empty or there are no more available spaces on the board. The winner is the player with the most dolmens, a group of at least 3 adjacent symbols of a colour, when seen from a bird’s eyes view. In case both players have the same number of dolmens, whoever has the largest dolmen wins the game.

One of the first noticeable features of Carnac is how it uses its pieces. Not only are the pieces of a fairly rare shape, but they have both colours on them (another quite uncommon feature in abstract games). This by itself would be enough to say Carnac is unique, but the manipulation of the pieces is what really sets it apart from other games. More specifically, I am referring to the protocol for tilting them.

First of all, I am not aware of many abstract games that rely on this kind of mechanism. To my knowledge, only Quarto (designed by Blaise Muller and published by Gigamic) precedes Carnac on the usage of this kind of “I cut, you choose” mechanism (besides the pie rule). This somewhat rare mechanism creates an interesting dynamic, engaging players at all times, since they play a role even when it is not their “active” turn (thus minimizing any feeling of downtime).

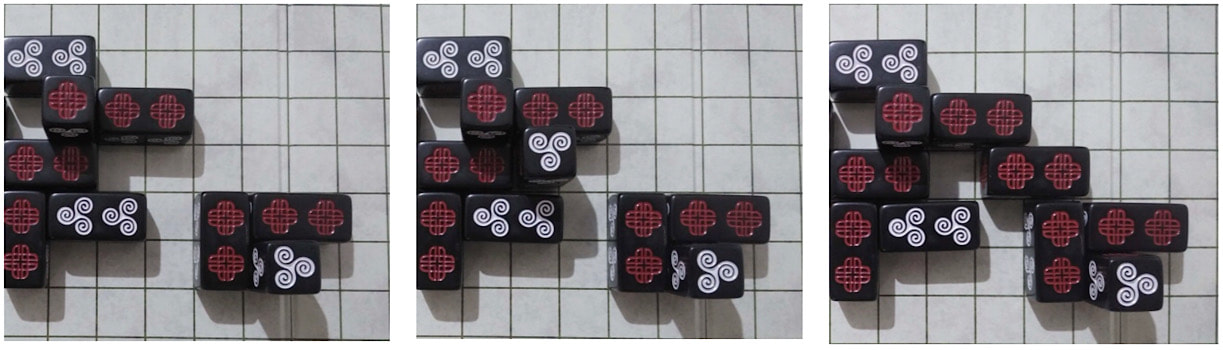

It also lets players experience different decisions throughout the game. The active player needs to pay attention to the sides they are providing to the passive player, as well as the possible positions resulting from the way the piece is placed: a good active player will limit the options available to the passive player and “induce” a particular tilting (or lack of) with good placement. Meanwhile the passive player gets to choose how the piece ultimately will end up (from the options provided by the active player, of course). To tilt a piece (or how to do it) is not as straightforward a decision as it might seem. One thing that novices may take some games to understand is how valid an option it is to leave the piece standing, for example. If the active player places a megalith in such a way where the passive player’s only tilting option will merge two dolmens (thus decreasing this player’s score by one), the passive player may choose to leave that piece as is (Figure 2).

One of the first noticeable features of Carnac is how it uses its pieces. Not only are the pieces of a fairly rare shape, but they have both colours on them (another quite uncommon feature in abstract games). This by itself would be enough to say Carnac is unique, but the manipulation of the pieces is what really sets it apart from other games. More specifically, I am referring to the protocol for tilting them.

First of all, I am not aware of many abstract games that rely on this kind of mechanism. To my knowledge, only Quarto (designed by Blaise Muller and published by Gigamic) precedes Carnac on the usage of this kind of “I cut, you choose” mechanism (besides the pie rule). This somewhat rare mechanism creates an interesting dynamic, engaging players at all times, since they play a role even when it is not their “active” turn (thus minimizing any feeling of downtime).

It also lets players experience different decisions throughout the game. The active player needs to pay attention to the sides they are providing to the passive player, as well as the possible positions resulting from the way the piece is placed: a good active player will limit the options available to the passive player and “induce” a particular tilting (or lack of) with good placement. Meanwhile the passive player gets to choose how the piece ultimately will end up (from the options provided by the active player, of course). To tilt a piece (or how to do it) is not as straightforward a decision as it might seem. One thing that novices may take some games to understand is how valid an option it is to leave the piece standing, for example. If the active player places a megalith in such a way where the passive player’s only tilting option will merge two dolmens (thus decreasing this player’s score by one), the passive player may choose to leave that piece as is (Figure 2).

Another interesting decision taken by the designer was to set a fixed number of pieces regardless of board size. Take into consideration that—at least in my experience—the vast majority of games end with an empty stockpile and you’ll see that there is a huge difference in covered spaces between the three provided board sizes. This fact has tactical/strategic implications: the smaller size is so cramped that forced tilting—or placements with no tilting option—is more frequent. In the larger size, it is harder to induce a particular tilting, given there is so much real estate on the board, but they do happen given pieces tend to be placed in clusters. The medium size is, as one can imagine, right in between the other two, and personally, my favourite to play.

Although Wentu didn’t invent any of the features in Carnac (shared pieces; dicubic pieces; I cut, you choose), by combining them, he created a unique game (and experience). Years ago, I stated it was one of the most original abstract games of the modern era, and I stand by my statement. Carnac, to me, is a great example of a modern abstract. It provides a good amount of decisions in a small playing time, it is beautiful to look at and it does not play like anything else. I highly recommend it.

PS You can try Carnac at boardspace.net.

Although Wentu didn’t invent any of the features in Carnac (shared pieces; dicubic pieces; I cut, you choose), by combining them, he created a unique game (and experience). Years ago, I stated it was one of the most original abstract games of the modern era, and I stand by my statement. Carnac, to me, is a great example of a modern abstract. It provides a good amount of decisions in a small playing time, it is beautiful to look at and it does not play like anything else. I highly recommend it.

PS You can try Carnac at boardspace.net.