Interview

[Questions by Rey Armenteros are italicized; responses from Dieter Stein are in plain text.]

This opportunity to interview Dieter Stein is a great pleasure for me. I have been playing your stacking trilogy, as well as other Dieter Stein games, for years. I have discussed the characteristics of your games with players over the years, making you into a household name (at least in my home). I would like to start with something close to me, and that is Abande. I’ve always fancied myself a decent Abande player until recently when I played the bot on spielstein.com. After a few decisive losses, it started to dawn on me that this game may have a deeper level of strategy than the light one I had assumed. What are the strategic options in Abande?

Thank you, it's a pleasure for me too. I feel honoured and let me first say, that I'm very grateful that I had the opportunity to live in a time where I could meet (in real life or online) so many people I could learn from and who influenced me or helped me to make my small contribution to the world of abstract games a reality.

Now, let's start with Abande. An Abande player mainly looks for the decisive spots and then tries to follow their spatial branching on the board, which is not easy to manage because these extension paths are based on a not yet established or often still undecided mesh of connections, which only in later phases of the game may give you clarity. New players often believe Abande is light, as all is controlled and limited to a reasonable calculation up to the number of three. But that's only the tactical part, the other more strategic part is really difficult to foresee.

Are there key opening moves in Abande? I ask because I am also thinking about Attangle. In both games, I play the edges, but other players have shown me the advantages of playing the middle spaces. Are there better starting positions in either game?

Like in almost all games with a defined border—and especially those with some kind of connectivity mechanism—edges have a strong impact on tactics as well as strategy, apart from limiting the playing time and thus making it a game attractive for humans in the first place. Edges often mean restriction and in Abande that means lack of connections but also mobility. I myself usually start in the middle to allow for more options and see how the situation progresses. However in this game you are confronted with additional restrictive rules. So it can get tricky very quickly even in more centred positions.

Speaking of crucial centre positions: Peter Danzeglocke, an experienced Go player contacted me a year or so after I had published Attangle and pointed to the perhaps too strong middle position in that game. I had to agree and found a way to attenuate the game in this regard, and—while working on it—we also added a nice mechanism of taking back the supporting piece of a capture.

Apart from dominating the centre, in Attangle it is surely advantageous to build up clusters of pieces which are easier to defend and surely these structures are even stronger at the edges. So as many players who follow this strategy found out, in Attangle it's more about territory than it would seem at first glance.

When I play Abande, I have a pleasant experience, and the same can be said for Paletto. I never feel tense. When you create your games, do you think about the player’s experience? Have you ever fine-tuned a game when facing player interaction that you felt was not ideal?

For me creating a game is a very intuitive thing and has very much to do with my own personal preferences and experiences. I think, first of all, as a designer you need to know your domain thoroughly. It's not only very helpful but actually a requirement to know many of the games (and concepts) already out there. Secondly, you should of course actually play them. Getting to know the rules mainly means to get the feel for a specific game and games in general, the mechanisms and—this is even more important—the emotions they induce. Just because play is an utterly human thing. By the way, when becoming more prolific you may even learn to feel a game by only reading the rules, as Christian Freeling would say. In a nutshell for me that is: know your domain and do your work for your audience—the players.

If a game works in the mathematical sense but fails on the emotional side, you may have a chance to rescue it by spotting and fixing one or two crucial points. But almost always, that's my experience, you had better archive the whole concept for some future enlightenment. So to finally answer your question: I rescued a previous "unentertaining" version of Tintas when the idea of a common pawn crossed my mind. In the earlier concept it was the last captured colour which determined the colour of the next capturing piece. It has been a concept quickly to grasp, but only after that small change was it suddenly fun, suddenly there was “play.”

I know, one could measure this repair work in terms of game-theoretical parameters, but we should not overlook that it induces mitigated forms of greed and the sublime feeling of well-considered restraint in the players' minds. Never disregard the mental dimension of play!

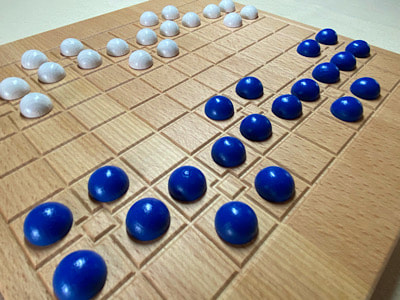

Paletto feels so well-balanced. It’s as if six color pieces is the perfect distribution for the board of that size. How did Paletto come into being? Were you thinking of Nim?

No, no, it came from another direction. It started with the game system called "Nestortiles" by my friend Néstor Romeral Andrés. As I mentioned, my way is intuition, in some meta-sense "playing with play": I was fooling around with the pieces and one imposing thought was to reduce a large connected structure piece by piece without ever splitting the whole thing. Two players assumed and given differently coloured pieces, it was quickly obvious that a player may use any number of one certain colour selected each turn. That made the game partisan and so in the end, Paletto turned out to be an entangled variant of Nim. So, as often in creative processes, the succession of development steps appear kind of reversed.

Regarding numbers, it often occurs to me that succeeding designs have intrinsic dimensions which are actually playability parameters. This is a personal preference of mine: I like to emphasize numeric harmony in my games: Mixtour is “five,” Paletto is “six,” Fendo is “seven,” Rincala is “eight,” Urbino is “nine.” This may sound too arcane, but I think these numbers and relations mirror and conclude the elegance and beauty of self-contained games. They are pointers to the mathematical background as well as the mystical function of numbers and relations.

This opportunity to interview Dieter Stein is a great pleasure for me. I have been playing your stacking trilogy, as well as other Dieter Stein games, for years. I have discussed the characteristics of your games with players over the years, making you into a household name (at least in my home). I would like to start with something close to me, and that is Abande. I’ve always fancied myself a decent Abande player until recently when I played the bot on spielstein.com. After a few decisive losses, it started to dawn on me that this game may have a deeper level of strategy than the light one I had assumed. What are the strategic options in Abande?

Thank you, it's a pleasure for me too. I feel honoured and let me first say, that I'm very grateful that I had the opportunity to live in a time where I could meet (in real life or online) so many people I could learn from and who influenced me or helped me to make my small contribution to the world of abstract games a reality.

Now, let's start with Abande. An Abande player mainly looks for the decisive spots and then tries to follow their spatial branching on the board, which is not easy to manage because these extension paths are based on a not yet established or often still undecided mesh of connections, which only in later phases of the game may give you clarity. New players often believe Abande is light, as all is controlled and limited to a reasonable calculation up to the number of three. But that's only the tactical part, the other more strategic part is really difficult to foresee.

Are there key opening moves in Abande? I ask because I am also thinking about Attangle. In both games, I play the edges, but other players have shown me the advantages of playing the middle spaces. Are there better starting positions in either game?

Like in almost all games with a defined border—and especially those with some kind of connectivity mechanism—edges have a strong impact on tactics as well as strategy, apart from limiting the playing time and thus making it a game attractive for humans in the first place. Edges often mean restriction and in Abande that means lack of connections but also mobility. I myself usually start in the middle to allow for more options and see how the situation progresses. However in this game you are confronted with additional restrictive rules. So it can get tricky very quickly even in more centred positions.

Speaking of crucial centre positions: Peter Danzeglocke, an experienced Go player contacted me a year or so after I had published Attangle and pointed to the perhaps too strong middle position in that game. I had to agree and found a way to attenuate the game in this regard, and—while working on it—we also added a nice mechanism of taking back the supporting piece of a capture.

Apart from dominating the centre, in Attangle it is surely advantageous to build up clusters of pieces which are easier to defend and surely these structures are even stronger at the edges. So as many players who follow this strategy found out, in Attangle it's more about territory than it would seem at first glance.

When I play Abande, I have a pleasant experience, and the same can be said for Paletto. I never feel tense. When you create your games, do you think about the player’s experience? Have you ever fine-tuned a game when facing player interaction that you felt was not ideal?

For me creating a game is a very intuitive thing and has very much to do with my own personal preferences and experiences. I think, first of all, as a designer you need to know your domain thoroughly. It's not only very helpful but actually a requirement to know many of the games (and concepts) already out there. Secondly, you should of course actually play them. Getting to know the rules mainly means to get the feel for a specific game and games in general, the mechanisms and—this is even more important—the emotions they induce. Just because play is an utterly human thing. By the way, when becoming more prolific you may even learn to feel a game by only reading the rules, as Christian Freeling would say. In a nutshell for me that is: know your domain and do your work for your audience—the players.

If a game works in the mathematical sense but fails on the emotional side, you may have a chance to rescue it by spotting and fixing one or two crucial points. But almost always, that's my experience, you had better archive the whole concept for some future enlightenment. So to finally answer your question: I rescued a previous "unentertaining" version of Tintas when the idea of a common pawn crossed my mind. In the earlier concept it was the last captured colour which determined the colour of the next capturing piece. It has been a concept quickly to grasp, but only after that small change was it suddenly fun, suddenly there was “play.”

I know, one could measure this repair work in terms of game-theoretical parameters, but we should not overlook that it induces mitigated forms of greed and the sublime feeling of well-considered restraint in the players' minds. Never disregard the mental dimension of play!

Paletto feels so well-balanced. It’s as if six color pieces is the perfect distribution for the board of that size. How did Paletto come into being? Were you thinking of Nim?

No, no, it came from another direction. It started with the game system called "Nestortiles" by my friend Néstor Romeral Andrés. As I mentioned, my way is intuition, in some meta-sense "playing with play": I was fooling around with the pieces and one imposing thought was to reduce a large connected structure piece by piece without ever splitting the whole thing. Two players assumed and given differently coloured pieces, it was quickly obvious that a player may use any number of one certain colour selected each turn. That made the game partisan and so in the end, Paletto turned out to be an entangled variant of Nim. So, as often in creative processes, the succession of development steps appear kind of reversed.

Regarding numbers, it often occurs to me that succeeding designs have intrinsic dimensions which are actually playability parameters. This is a personal preference of mine: I like to emphasize numeric harmony in my games: Mixtour is “five,” Paletto is “six,” Fendo is “seven,” Rincala is “eight,” Urbino is “nine.” This may sound too arcane, but I think these numbers and relations mirror and conclude the elegance and beauty of self-contained games. They are pointers to the mathematical background as well as the mystical function of numbers and relations.

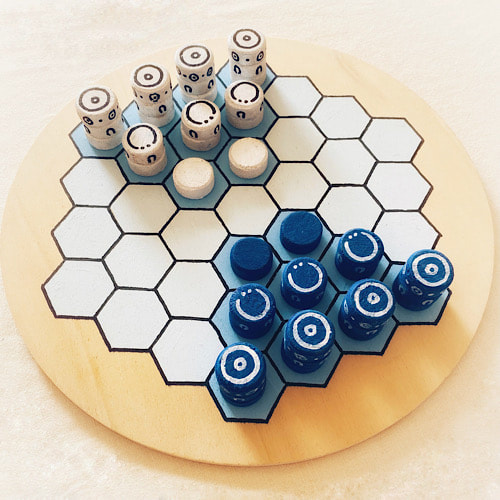

In Mixtour, you revisited some of the dynamics in your stacking trilogy. To me, there are notions of Accasta Pari in it. It feels slippery, because the attacks can suddenly change depending on an unexpected move. Did you work off of a game like Accasta or Abande and looked for possibilities, or was it more about trying something that you might have liked to see in the previous stacking games?

Mixtour owes its existence to the "Stacking Contest" encouraged by Daniel Shultz in the newsgroup rec.games.abstract in December 2010. When I was thinking about the stacking concept in general I had the idea to disregard the two “unwritten laws of stacking games,” which are: First, the piece on top owns the whole stack, and second, towers have some kind of power presented through their height. This led me to Mixtour—actually very quickly. Playing around with a prototype it suddenly struck me to kind of reverse the movement of pieces. It was a matter of seconds, everything fell into place. Although it needed a small second thought regarding the final goal, it was an overwhelming moment.

I am a novice at Mixtour, but I get the sense that it is a deeper game than the ones from the stacking trilogy. Do you agree? Are there levels of gameplay that might escape a novice?

Its depth is comparable to Abande or Attangle - that is: not so deep in general. But I think that's not the main point in this game. The thing is it's hard to see the move options as well as the impact of changes on target and origin spaces when splitting a tower. I haven't played with anyone yet who hasn't had trouble with this. It's so counter-intuitive and that's actually what makes it fun—at least to some. Sooner or later you will learn that crazy backward thinking but then you will still be confronted with sudden turnarounds and moves you never thought of before.

Mixtour and Urbino allows both players to move the same pieces. It opens up many more possibilities in player turns. Other games have done this. Which ones were you thinking about when creating these games?

The common pieces in Urbino have their roots in Tintas. When I worked on a three player variant for Tintas I experimented with two pieces which belonged in an alternating way to either of the two pairs of the player trio. I didn't succeed but it opened up the possibility of intersection points when considering them as chess queens. The idea had to wait for half a year when I used it for Urbino's architects.

Mixtour owes its existence to the "Stacking Contest" encouraged by Daniel Shultz in the newsgroup rec.games.abstract in December 2010. When I was thinking about the stacking concept in general I had the idea to disregard the two “unwritten laws of stacking games,” which are: First, the piece on top owns the whole stack, and second, towers have some kind of power presented through their height. This led me to Mixtour—actually very quickly. Playing around with a prototype it suddenly struck me to kind of reverse the movement of pieces. It was a matter of seconds, everything fell into place. Although it needed a small second thought regarding the final goal, it was an overwhelming moment.

I am a novice at Mixtour, but I get the sense that it is a deeper game than the ones from the stacking trilogy. Do you agree? Are there levels of gameplay that might escape a novice?

Its depth is comparable to Abande or Attangle - that is: not so deep in general. But I think that's not the main point in this game. The thing is it's hard to see the move options as well as the impact of changes on target and origin spaces when splitting a tower. I haven't played with anyone yet who hasn't had trouble with this. It's so counter-intuitive and that's actually what makes it fun—at least to some. Sooner or later you will learn that crazy backward thinking but then you will still be confronted with sudden turnarounds and moves you never thought of before.

Mixtour and Urbino allows both players to move the same pieces. It opens up many more possibilities in player turns. Other games have done this. Which ones were you thinking about when creating these games?

The common pieces in Urbino have their roots in Tintas. When I worked on a three player variant for Tintas I experimented with two pieces which belonged in an alternating way to either of the two pairs of the player trio. I didn't succeed but it opened up the possibility of intersection points when considering them as chess queens. The idea had to wait for half a year when I used it for Urbino's architects.

Urbino is such a wonderful game! The blocking aspect in Urbino goes beyond the conventional mode you see in a game such as Amazons, because it has to do with the positions of both Architects and the target space. As available areas get smaller, areas without either Architect can get locked out. For me, games of Amazon fizzle out, because at some point in the middle of the game, it is obvious who is going to win, which necessitates the losing player to resign. From my experience with Urbino, it has more of a climactic edge. How did you discover this dynamic? I can see traces of it in Attangle, but I don’t remember seeing this before.

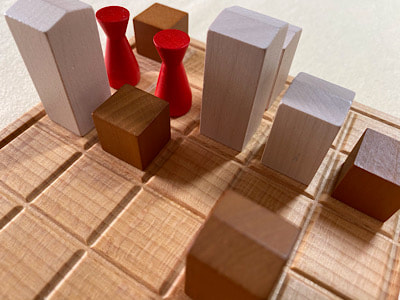

Thank you very much. In the beginning there was a game I called "Polar", which implements the idea of piece groups that consist of a maximum of one block for each of the two players' pieces. The idea was already two years old and I just forgot to finalize and publish it.

Then I was working on a game which I wanted to have a kind of city building theme. It should definitely be called “Urbino” after the most beautiful Italian town with a not less astonishing history. Also, the name actually translates to “little town,” the perfect name for my nascent game. It should also have some more complex, even “Euro game” style scoring mechanism.

I have visited Urbino many times and I have been to their “Festa dell'Aquilone,” the annual festival of kites where the different districts of the town compete against each other. That way, I rediscovered Polar. The groups were the perfect match for Urbino's quartieri. Sticking to the subject I now discovered streets, open and private places. I continued in this style and finally added the Architects, who were unemployed since the work on three-player Tintas. They came to restrict the building of groups in a way that opened up a whole new field of tactical possibilities. So again, everything grew in a mixture of personal experiences and preferences along the path of game development, which luckily ended up in a deep and entertaining game.

Here I finally have to mention Gerhards Spiel und Design, the publisher. Ludwig Gerhards, a genius when it comes to transforming game concepts into physical wooden objects once again did an enormous job with Urbino. The roofs of the palaces and towers have got that typical Mediterranean angle and we dressed the Architects like the great historical figure which is Federico da Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino.

The way I have learned the division between tactics and strategy is that tactics is the analytical portion of assessing the situation. Strategy is not just the long term plan of where I would like to be after a certain number of moves, it is the gut feeling. When I play a game, I try to think about when in the game I have to switch from one type of thinking to the other. For example, I sometimes think Chess follows the arc of starting with both strategy and tactics and then finishing in mostly tactics. Is there an arc in Urbino? If so, how would you trace its path?

I think it's justified to say Urbino shows a very variable and therefore lasting playing experience. On the surface you will observe similar progress as in many other games like the number of possible moves steadily decreasing and tactics becoming more and more important over strategy. But the outcome of Urbino is often more undecided, because of the score goal and moreover, because of how the scores are actually achieved through majority. Investments can go to waste, there are chances to pocket a temporary winning score by isolating the Architects and there are the big surprises of a late unification or acquisition of large decisive groups.

Are there set strategies in Urbino? With an open board at the start, Urbino makes me wonder if the strategic choices come after several moves. Or is there an approach you can take right from the opening?

I'm sorry, I played a lot of Urbino in the last years and I think I made some progress, but I haven't found a certain strategy which seems to be valid for each and every game. Sometimes you will see players choosing a more strategic approach, sometimes you find yourself engaged in some tactical local battle in the very beginning of a match. It's certainly easier to unfold your own plan in later phases of the game.

Thank you very much. In the beginning there was a game I called "Polar", which implements the idea of piece groups that consist of a maximum of one block for each of the two players' pieces. The idea was already two years old and I just forgot to finalize and publish it.

Then I was working on a game which I wanted to have a kind of city building theme. It should definitely be called “Urbino” after the most beautiful Italian town with a not less astonishing history. Also, the name actually translates to “little town,” the perfect name for my nascent game. It should also have some more complex, even “Euro game” style scoring mechanism.

I have visited Urbino many times and I have been to their “Festa dell'Aquilone,” the annual festival of kites where the different districts of the town compete against each other. That way, I rediscovered Polar. The groups were the perfect match for Urbino's quartieri. Sticking to the subject I now discovered streets, open and private places. I continued in this style and finally added the Architects, who were unemployed since the work on three-player Tintas. They came to restrict the building of groups in a way that opened up a whole new field of tactical possibilities. So again, everything grew in a mixture of personal experiences and preferences along the path of game development, which luckily ended up in a deep and entertaining game.

Here I finally have to mention Gerhards Spiel und Design, the publisher. Ludwig Gerhards, a genius when it comes to transforming game concepts into physical wooden objects once again did an enormous job with Urbino. The roofs of the palaces and towers have got that typical Mediterranean angle and we dressed the Architects like the great historical figure which is Federico da Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino.

The way I have learned the division between tactics and strategy is that tactics is the analytical portion of assessing the situation. Strategy is not just the long term plan of where I would like to be after a certain number of moves, it is the gut feeling. When I play a game, I try to think about when in the game I have to switch from one type of thinking to the other. For example, I sometimes think Chess follows the arc of starting with both strategy and tactics and then finishing in mostly tactics. Is there an arc in Urbino? If so, how would you trace its path?

I think it's justified to say Urbino shows a very variable and therefore lasting playing experience. On the surface you will observe similar progress as in many other games like the number of possible moves steadily decreasing and tactics becoming more and more important over strategy. But the outcome of Urbino is often more undecided, because of the score goal and moreover, because of how the scores are actually achieved through majority. Investments can go to waste, there are chances to pocket a temporary winning score by isolating the Architects and there are the big surprises of a late unification or acquisition of large decisive groups.

Are there set strategies in Urbino? With an open board at the start, Urbino makes me wonder if the strategic choices come after several moves. Or is there an approach you can take right from the opening?

I'm sorry, I played a lot of Urbino in the last years and I think I made some progress, but I haven't found a certain strategy which seems to be valid for each and every game. Sometimes you will see players choosing a more strategic approach, sometimes you find yourself engaged in some tactical local battle in the very beginning of a match. It's certainly easier to unfold your own plan in later phases of the game.

Your article “Volo: Bird Flight in a Game” records the process of inventing a game. Thinking of Ordo, you realized that the Ordo moves were similar to those in flocks of birds, and so you took that spark to create a game about this phenomenon. Actually, your article is an invaluable document of the creative process in game design, and the game itself is a thematic revelation. I admire that this abstract game not only has a unique theme, but it shares a poetic view of it. I think it telling that theme was an important aspect of making this game. What are your thoughts on themes in games? Do you sometimes begin with the theme, or was Volo an exception?

I already mentioned that intuition takes a large part in my work. Although I'm well aware of the fact that games, especially combinatorial games, are pure mathematical objects, we should not forget that they also have a cultural, humanistic side—simply because, like books, they transport and induce emotions. So my way to work is often based on personal experiences which can be described as story-telling or following a theme. Such a motif can be carried out throughout the process and still made perceptible in the final work if it presents or emphasizes the sensational dimension—also in games which should normally be filed under “abstract.” I see no problem with that. Of course, the situation is quite different when marketing people are tagging an arbitrary theme onto a game product in order to increase sales. It may work, but that's not exactly the same thing.

The creation of Volo leads me to the question of how did you start inventing games? I have read that you’ve been doing it since you were a child, when you were first forming Accasta.

Yes, it started when I was 10 years old. I began to alter the rules of the games we played in the family. These were mostly the simple dice games, but I also started to learn chess and I played a lot with my uncle. Soon after that I began to develop a love for abstract games which appeared on the market in the 1970s. I still have a quite representative collection of game boxes from this era like "Orion," "Duell," or "Viaduct" to name a few rarities. As those minimalistic games were hard to vary I soon ended up in trying new ideas from the ground up. Accasta was my long-term project which saw lots of changes through the years. All of them were tiny failures and then successes from which I learned much that I know and use today.

I already mentioned that intuition takes a large part in my work. Although I'm well aware of the fact that games, especially combinatorial games, are pure mathematical objects, we should not forget that they also have a cultural, humanistic side—simply because, like books, they transport and induce emotions. So my way to work is often based on personal experiences which can be described as story-telling or following a theme. Such a motif can be carried out throughout the process and still made perceptible in the final work if it presents or emphasizes the sensational dimension—also in games which should normally be filed under “abstract.” I see no problem with that. Of course, the situation is quite different when marketing people are tagging an arbitrary theme onto a game product in order to increase sales. It may work, but that's not exactly the same thing.

The creation of Volo leads me to the question of how did you start inventing games? I have read that you’ve been doing it since you were a child, when you were first forming Accasta.

Yes, it started when I was 10 years old. I began to alter the rules of the games we played in the family. These were mostly the simple dice games, but I also started to learn chess and I played a lot with my uncle. Soon after that I began to develop a love for abstract games which appeared on the market in the 1970s. I still have a quite representative collection of game boxes from this era like "Orion," "Duell," or "Viaduct" to name a few rarities. As those minimalistic games were hard to vary I soon ended up in trying new ideas from the ground up. Accasta was my long-term project which saw lots of changes through the years. All of them were tiny failures and then successes from which I learned much that I know and use today.

Which game designers have influenced you the most? This could include game design itself or game theory, or it could simply be game designers whose games you enjoy playing.

Sure, there are many who influenced me. Sometimes because of the way they explained their motivation for designing games, sometimes because they created designs that I loved to play and made me wonder how one can achieve such beautiful things which manage to absorb people's minds. I had a book called Das große Krone Spielebuch, which described about 150 games—all with hardly displaying any actual components, but that stimulated my desire to invent even more. I read Sid Sackson's book A Gamut of Games, played and—as I said—collected almost all the now classic abstracts. Later I had the pleasure to meet Reinhold Wittig, Michail Antonow, and Kris Burm. I now consider Fred Horn, Néstor Romeral Andrés and Cameron Browne as friends and soul mates who steadily influence me.

When I play Homeworlds or Epaminondas, I recognize a great range of creativity you are given by the game’s rules. It empowers the player, and it offers moments when you can feel suddenly clever for something that you figured out and used effectively. When you play a game, does your inventor’s cap come on, or are you immersed in the game? How is playing a game also a creative activity? Which games do you think lend a broad range of creativity to a player?

Like any other I'm normally totally absorbed by a good game. But at the end, especially when playing a game with my daughter who I often consult when it comes to my own designs, we are talking about the overall experience and maybe some things and details we like or dislike. So, I leave the cap off while playing but cannot quite resist to grasp it afterwards. It's inevitable.

Games that lend creativity to players? Oh, that's how you define creativity. I myself link that term to an activity in a much more open space. Games in contrast are defined as small worlds with strict rules. You may describe a player as a creative actor, but there's certainly a substantial difference. And that's also a good thing! It's not about getting lost in possibilities, in fact it's the limitation which creates the game in the first place.

In classic games like Chess, we have inherited established strategies. I have wondered if and when contemporary games acquire those strategies, how they will alter the game experience. But I also wonder if contemporary game design does not really work in that sphere of specific strategies, since they are quite different from older games. Honestly, I have no idea, but it is something that I have thought about. Do you have any ideas about this or about differences between great modern games and their classic forebears?

It seems like an interesting question. Well, when we look at abstract games we will quickly either locate—even insignificant—design flaws or perfection, which in some sense can be equated with timelessness and that in turn lets the question come to nothing.

Many regard Go an ideal game. What is your ideal game?

I have to agree, there is no game like Go. Not only because of its most beautiful simplicity, which on the other hand opens up a manifold strategic world, but also because of the social and cultural dimension it created and still reflects. You can feel this when comparing it with another often named candidate for Abstract Zero which is Hex. Admittedly, it has a much shorter history, but, same as Go, it's also a quintessential game of unsurpassable purity with a straightforward goal, perhaps even more next to perfection as Go. But in my eyes it somehow falls short when it comes to telling a story.

Sure, there are many who influenced me. Sometimes because of the way they explained their motivation for designing games, sometimes because they created designs that I loved to play and made me wonder how one can achieve such beautiful things which manage to absorb people's minds. I had a book called Das große Krone Spielebuch, which described about 150 games—all with hardly displaying any actual components, but that stimulated my desire to invent even more. I read Sid Sackson's book A Gamut of Games, played and—as I said—collected almost all the now classic abstracts. Later I had the pleasure to meet Reinhold Wittig, Michail Antonow, and Kris Burm. I now consider Fred Horn, Néstor Romeral Andrés and Cameron Browne as friends and soul mates who steadily influence me.

When I play Homeworlds or Epaminondas, I recognize a great range of creativity you are given by the game’s rules. It empowers the player, and it offers moments when you can feel suddenly clever for something that you figured out and used effectively. When you play a game, does your inventor’s cap come on, or are you immersed in the game? How is playing a game also a creative activity? Which games do you think lend a broad range of creativity to a player?

Like any other I'm normally totally absorbed by a good game. But at the end, especially when playing a game with my daughter who I often consult when it comes to my own designs, we are talking about the overall experience and maybe some things and details we like or dislike. So, I leave the cap off while playing but cannot quite resist to grasp it afterwards. It's inevitable.

Games that lend creativity to players? Oh, that's how you define creativity. I myself link that term to an activity in a much more open space. Games in contrast are defined as small worlds with strict rules. You may describe a player as a creative actor, but there's certainly a substantial difference. And that's also a good thing! It's not about getting lost in possibilities, in fact it's the limitation which creates the game in the first place.

In classic games like Chess, we have inherited established strategies. I have wondered if and when contemporary games acquire those strategies, how they will alter the game experience. But I also wonder if contemporary game design does not really work in that sphere of specific strategies, since they are quite different from older games. Honestly, I have no idea, but it is something that I have thought about. Do you have any ideas about this or about differences between great modern games and their classic forebears?

It seems like an interesting question. Well, when we look at abstract games we will quickly either locate—even insignificant—design flaws or perfection, which in some sense can be equated with timelessness and that in turn lets the question come to nothing.

Many regard Go an ideal game. What is your ideal game?

I have to agree, there is no game like Go. Not only because of its most beautiful simplicity, which on the other hand opens up a manifold strategic world, but also because of the social and cultural dimension it created and still reflects. You can feel this when comparing it with another often named candidate for Abstract Zero which is Hex. Admittedly, it has a much shorter history, but, same as Go, it's also a quintessential game of unsurpassable purity with a straightforward goal, perhaps even more next to perfection as Go. But in my eyes it somehow falls short when it comes to telling a story.

It seems that the world of abstract games (not including the institutions of Chess and Go) is a quiet community that does not make a gigantic marketplace impact. Will it always be like this? Is this good or bad? What is the future of abstract games?

When you look at the history of games you can easily go back 5,000 years from now. And these first concepts are already "abstracts" in the contemporary sense. Games are not only part of human history, they are—abstract games even more—a manifestation of humanity. Again, they may be mathematical entities, but their true purpose is “play,” which belongs to a complete other reality, the reality of feeling and acting as a human being.

For me, marketing is mainly about the boxes and the presentation: Games should be presented in an appropriate form, like drinking wine out of elegant glasses rather than paper cups. But it's not about the very existence of a game. If it's in the world, it will live forever and interested people will get access to it sooner or later. If there's only a tiny community around a certain game it doesn't matter.

If you ask me about the future of (abstract) games, however, we'll certainly have to talk about artificial intelligence. The progress in this field is enormous and it seems that games count as the first victims in this development. I don't see that. Games won't disappear as long as there are still humans around. Look at what AlphaZero did to Go and recently Chess: it didn't kill these games at all, it just revealed new forms of play and made the game even more attractive to humans. After all, machines don't "play" in the strict sense of the word: Neither random moves nor the perfect rush through the decision tree of a game isn't play. As Cameron Browne has shown, already today it's perfectly possible to algorithmically create complete new games with feedback processes even to optimize the entertainment factor.

However, it will have a strong impact on game designers and may even question their work as a whole. I think Cameron saw this too and shied away from that. He started the incredibly extensive and long overdue research on the human culture of games with the Ludii project, which is fantastic.

My hope is that humanism will survive, it's not less than the ultimate challenge for mankind. We will have to find new ways—but choose carefully.

Do you play other types of games, like Euro games?

I have two kids, so—yes of course! They are grown-up now, but still we love to play simple and fun games like Stone Age or Dixit when we meet.

Besides games, do you have any other creative endeavours?

Yes, I compose music. I don't play an instrument though, it's computer music of the minimal repetitive kind.

Are there any new upcoming projects you would like to talk about?

My main interest is currently not in new designs but more in caring for my old ones. I'm planning to further develop my website spielstein.com. I'm going to add more tactical and strategic insights and extend the online gaming platform.

But maybe a new idea pops up in my head in the near future. As always, I cannot influence that. ◾️

Thank you very much both to Rey Armenteros and Dieter Stein for this interesting interview. It is fascinating to get some insight into the game design process from one of the most prolific and successful developers of abstract games in this century. Beautiful wooden editions of most of Dieter Stein's games are available from Gerhards Spiel und Design. These are classic designs for classic games. Many of the games are playable remotely at Dieter's website, spielstein.com, either with human opponents or an AI. Dieter's trilogy of stacking games, Abanda, Accasta, and Attangle, as well as his game Ordo, are playable at SuperDuperGames. I review Urbino in this issue, and speak a bit about Accasta in the blurb for the cover page. I am hoping to have an annotated game of Urbino in the next issue and to have further opportunities to present Dieter's games in more detail. ~ Ed.

When you look at the history of games you can easily go back 5,000 years from now. And these first concepts are already "abstracts" in the contemporary sense. Games are not only part of human history, they are—abstract games even more—a manifestation of humanity. Again, they may be mathematical entities, but their true purpose is “play,” which belongs to a complete other reality, the reality of feeling and acting as a human being.

For me, marketing is mainly about the boxes and the presentation: Games should be presented in an appropriate form, like drinking wine out of elegant glasses rather than paper cups. But it's not about the very existence of a game. If it's in the world, it will live forever and interested people will get access to it sooner or later. If there's only a tiny community around a certain game it doesn't matter.

If you ask me about the future of (abstract) games, however, we'll certainly have to talk about artificial intelligence. The progress in this field is enormous and it seems that games count as the first victims in this development. I don't see that. Games won't disappear as long as there are still humans around. Look at what AlphaZero did to Go and recently Chess: it didn't kill these games at all, it just revealed new forms of play and made the game even more attractive to humans. After all, machines don't "play" in the strict sense of the word: Neither random moves nor the perfect rush through the decision tree of a game isn't play. As Cameron Browne has shown, already today it's perfectly possible to algorithmically create complete new games with feedback processes even to optimize the entertainment factor.

However, it will have a strong impact on game designers and may even question their work as a whole. I think Cameron saw this too and shied away from that. He started the incredibly extensive and long overdue research on the human culture of games with the Ludii project, which is fantastic.

My hope is that humanism will survive, it's not less than the ultimate challenge for mankind. We will have to find new ways—but choose carefully.

Do you play other types of games, like Euro games?

I have two kids, so—yes of course! They are grown-up now, but still we love to play simple and fun games like Stone Age or Dixit when we meet.

Besides games, do you have any other creative endeavours?

Yes, I compose music. I don't play an instrument though, it's computer music of the minimal repetitive kind.

Are there any new upcoming projects you would like to talk about?

My main interest is currently not in new designs but more in caring for my old ones. I'm planning to further develop my website spielstein.com. I'm going to add more tactical and strategic insights and extend the online gaming platform.

But maybe a new idea pops up in my head in the near future. As always, I cannot influence that. ◾️

Thank you very much both to Rey Armenteros and Dieter Stein for this interesting interview. It is fascinating to get some insight into the game design process from one of the most prolific and successful developers of abstract games in this century. Beautiful wooden editions of most of Dieter Stein's games are available from Gerhards Spiel und Design. These are classic designs for classic games. Many of the games are playable remotely at Dieter's website, spielstein.com, either with human opponents or an AI. Dieter's trilogy of stacking games, Abanda, Accasta, and Attangle, as well as his game Ordo, are playable at SuperDuperGames. I review Urbino in this issue, and speak a bit about Accasta in the blurb for the cover page. I am hoping to have an annotated game of Urbino in the next issue and to have further opportunities to present Dieter's games in more detail. ~ Ed.